By Brandi Morin (Cree/Iroquois)

In a valley surrounded by towering, forest-clad mountains along Ecuador's Cordillera del Cóndor, a Shuar community of roughly 400 people has made its home for generations. They have thrived here alongside the jungle's abundance, the rivers' clear, rushing waters, and the deep bonds of their culture, traditions, and language. The Shuar Arutam Makiuants hope to preserve this way of life for generations to come. But for 20 years, a looming threat has cast a shadow over their future: a massive copper mine development at their doorstep.

Despite repeatedly refusing permission for mining on their ancestral lands, the company, which has changed hands multiple times and is now owned by Solaris Resources, is preparing to begin full-scale extraction. For the Shuar Maikiuants, everything hangs in the balance: their land, their food, their health, their ancestral connections, and their future. They believe that if the land becomes polluted, they will perish.

The outside of a traditional Shaur kitchen made from items foraged from the jungle.

The Shuar ancestral territory of Cordillera del Cóndor stands as one of Earth's most extraordinary biodiversity hotspots, an isolated mountain range where mist-shrouded mountains rise abruptly from the Amazon basin, creating a biological treasure trove that scientists believe harbors the richest flora diversity of any comparable area in South America. Some 4,000 plant species, including 65 recently discovered orchids and one of Ecuador's few carnivorous plants, thrive in ecosystems ranging from dwarf cloud forests carpeted in moss to valleys thick with tree ferns and epiphytes. The region's 613 bird species rival the massive Yasuní in avian diversity, while its forests shelter jaguars, spectacled bears, spider monkeys, and the endangered Andean tapir alongside 165 amphibian and 137 reptile species, many found nowhere else on Earth.

This unique geography, where Amazonian and Andean species converge on nutrient-poor sandy soils unlike any in the surrounding Andes, has created an evolutionary laboratory of endemic life. The mountain range feeds the major rivers of Ecuador's southern Amazon, providing water to communities below while harboring species still being discovered. Scientists describe much of the Cordillera as terra incognita, largely unexplored and unchanged despite mounting threats from extraction.

The community has recently intensified its resistance, even as the mining company has signed benefit agreements with neighboring Shuar groups, sowing tension and division among once-united communities. In early November, leadership made the decision to reactivate the checkpoint on the road that passes through Maikiuants leading to the mine.

Youth play soccer in the center of the Maikiuaints community.

“We activated 24-hour control,” says Maikiuants elected President Tsunki Chup, who explains it’s a tactic used by the community in an attempt to halt supplies to the mining operation. "There isn't a set end date for when it will cease or when we're going to suspend it; it's still unknown."

The actions have caused tensions with Solaris workers. "They got upset and went to the ombudsman's office several times to resolve the issue because they were losing their jobs, they were losing time, they were losing gas." Two weeks in, a frustrated Solaris employee attempted to attack one of the Indigenous guards at the checkpoint. “It was with malicious intent when a car tried to run over the checkpoint guard. So, we resisted. We endured all of that," Chup says.

The mining project has fractured the once-harmonious, neighboring communities of Warintz and Yawi Shuar, with whom the company brokered Impact Benefit Agreements, and the Maikiuants, into opposing camps, pitting relatives against one another. Some families depend on company jobs while others resist extraction, and now the two live in mutual distrust and estrangement.

"We were peaceful, we lived in harmony, we lived in tranquility. But the arrival of the outsiders, the national companies, have divided us, and are still dividing us, even though we are brothers, cousins, nephews, very close relatives, from parents to children," Chup says.

The checkpoint on a road going through communities set up by Maikiuants leadership to assert sovereignty over access to the mining project.

Solaris was headquartered in Canada until 2025, when it announced a move to Quito after the Canadian government blocked Chinese investment in the project over national security concerns. Despite the relocation, the company remains largely controlled by Canadian interests. Vancouver-based billionaire Richard Warke, who made his fortune in mining, owns 36% of Solaris, while his company Augusta Investments Inc. holds another 35%. The second-largest individual shareholder is Toronto-born Daniel Earle, a former Solaris CEO, who owns 4.3%. The remainder is held by UK and American investment firms along with institutional owners.

Canada dominates the global mining industry, with up to 75% of the world's mining and exploration companies headquartered there. This dominant position has drawn intense scrutiny over international mining violations, as Canadian-listed firms are frequently linked to environmental destruction, human rights abuses, and violence against community defenders abroad, particularly in Latin America. Reports from the Justice and Corporate Accountability Project have documented numerous incidents involving Canadian companies, including 44 deaths and hundreds of injuries in Latin America alone. Critics argue the Canadian government fails to effectively regulate its companies' operations abroad, while Canadian mining operations are routinely accused of contaminating water sources, destroying ecosystems, and violating indigenous rights across continents.

The entrance to the Maikuiants community.

Among other strategies Solaris employs are the age-old divide and conquer, notes Chup. "For the mining companies, it's better that the families are divided among themselves, to let them have conflicts. The important thing for the companies is that the people and the landowners exterminate each other so they can exploit everything they want," he says.

The proposed large-scale, open-pit copper, gold, and molybdenum mine plans to extract 4 million metric tonnes of copper from Shuar Arutam territory, with catastrophic environmental, health, and social consequences. The project risks widespread deforestation, biodiversity loss, and contamination of soil and water systems that the Shuar depend on for survival, while large-scale disturbance of hydrological and geological systems could trigger irreversible ecological damage from mine tailing spills and waste overflow.

A mural in Limon Indanza, a town nearest to Maikiuants which depicts a Shaur woman protecting her territory from miners.

Beyond environmental destruction, the mine threatens Maikiaunts with forced displacement, land dispossession, and the loss of Traditional Knowledge and cultural practices, compounded by increased militarization, corruption, violence, and social problems like alcoholism and prostitution. Health impacts range from environmental diseases and water-borne illnesses to mental health crises, accidents, and violence-related injuries, with women facing specific gender-based impacts.

At stake is not merely copper extraction, but the survival of an Indigenous way of life, the integrity of critical Amazon ecosystems, and the fundamental human rights of communities who have stewarded these lands for generations. Pinchu Ankuash, the elected Vice President of Maikiuants, says he recently caught mining workers scoping out their territory in the jungle without permission to be there.

"We suspected that they had entered our area without our consent to do some biotic monitoring. So, one day we went, accompanied by the trustee, to verify if that was true. And yes, it was true. We found the personnel who do biotic monitoring right on that path at the intersection,” says Ankuash. "I personally told them, 'You have to leave and go back into the territory of Warintz now because we haven't agreed to this type of activity—they had gone 82 meters in. And another one, 800 meters in, doing monitoring without our consent.'"

Marcos Ankuash represents the youth of Maikiuants, “The territory is life for us. And that is why I invite the world to become aware of the destruction of the Amazon, of the foreign extractive activities taking place here in the territory, and to reflect deeply on all the extractive companies that are here in my territory,” he said.

The small community of Maikiuants faces a David-and-Goliath struggle, deploying a modest contingent of Indigenous guards to monitor their ancestral territory against a multimillion-dollar mining operation with seemingly limitless resources. They refuse to settle with compensation or buyouts, says Ankuash. "The company sees it as easier to solve this; they want to compensate. For us, that's not enough. We don't demand compensation. We demand reparations. If we accept compensation, they would be violating many rights of nature, our rights as Indigenous people, and we would continue paying."

"We've argued scientifically, anthropologically, and environmentally,” he continues. “But they haven't been able to substantiate their claims. So, they're backing down a bit and looking for another way to attack us."

Ecuador’s new Social Transparency Law passed in late 2025, is a high concern for Maikiuants, says Ankuash. It has the power to completely dissolve civil society organizations without due process or judicial oversight—a weapon already being wielded against groups defending ancestral territories from extraction. The law has specifically targeted prominent anti-extractivism organizations, including the Ceibo Alliance Foundation and Frente Nacional Antiminero, with authorities accusing them of ties to organized crime and irregular funding as a pretext to criminalize legitimate territorial defense.

Ecuador’s new Social Transparency Law passed in fall2025 is a high concern, says Maikiuants elected Vice President Pinchu Ankuash-it has the power to completely dissolve civil society organizations without due process or judicial oversight-a weapon already being wielded against groups defending ancestral territories from extraction.

By forcing organizations to disclose sensitive information about members, beneficiaries, and project locations—data that exponentially increases risks of extortion, harassment, and assassination—while simultaneously stripping away their legal status for non-compliance, the law creates a mechanism to systematically dismantle Indigenous resistance. The government can now eliminate organizations by administrative fiat, stripping Indigenous Nations of their ability to assert constitutional rights to prior consultation, effectively clearing the path for mining and oil development across the Amazon while communities are left legally defenseless.

"There's a new law, a social transparency law. Because through that, those who demonstrate, those who are against state policy, they can disavow us. We would be left without legal status, and they wouldn't even consult us for consent when they take away our legal status. So that's how they weaken us,” explains Ankuash.

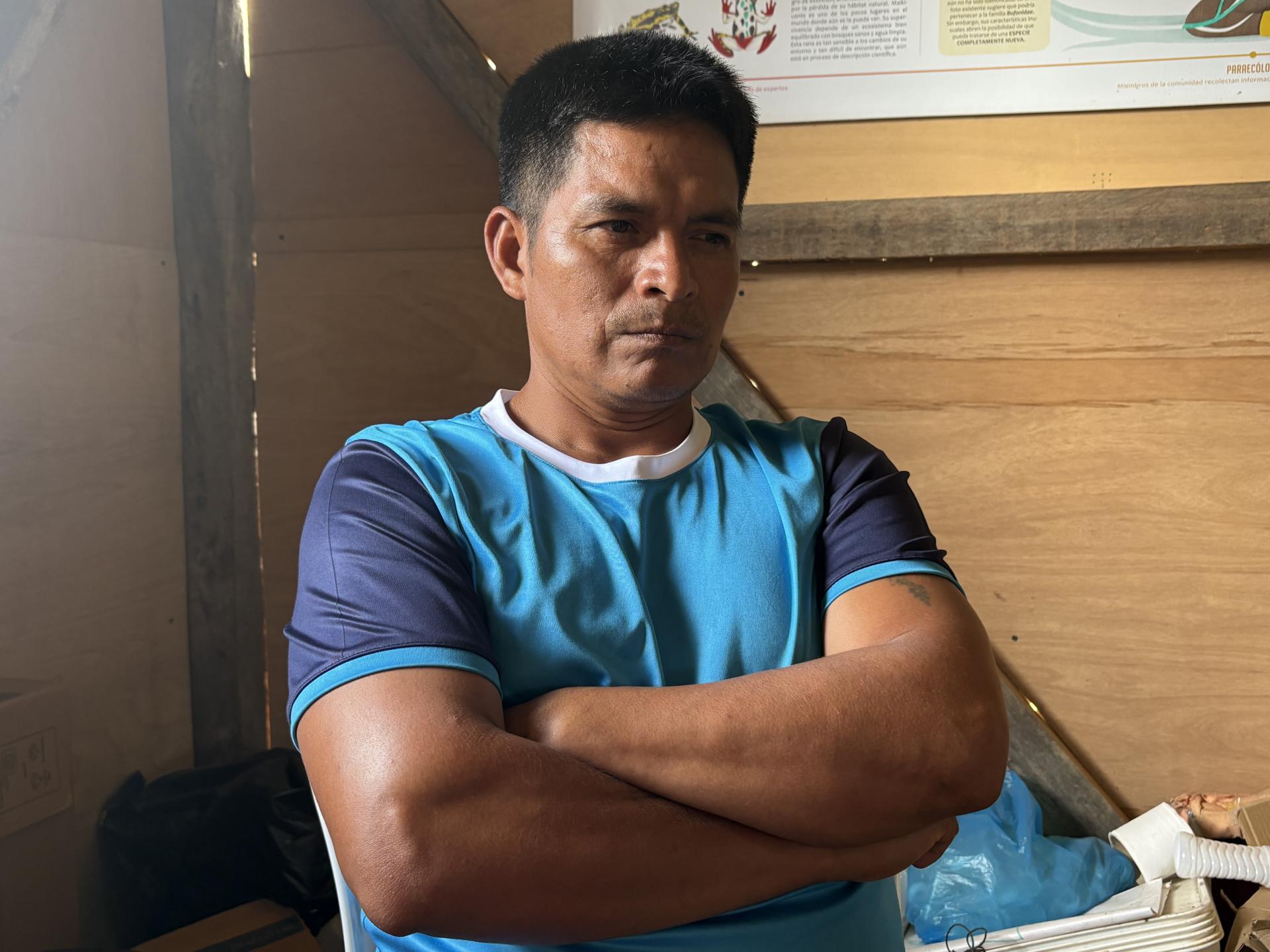

Maikiuants elected president Tsunki Chup says he authorized a 24/hour/day checkpoint on the road that passes through the community to the mine.

Tsunki Chup works in the community office while his son watches, “As long as the company (Solaris) remains in the territory, this will continue to create tension among the families."

Solaris Resources has fortified its position against community resistance through a 2022 Investment Protection Agreement with Ecuador that shields the company with sweeping protections including prohibition of confiscation, guaranteed legal security, tax stability, and access to international arbitration for any disputes, effectively insulating the $3.7 billion Warintza project from challenges by Indigenous communities like Maikiuants. The agreement locks in a reduced 20% corporate income tax rate and exempts the company from capital outflow taxes and import duties, while a 2025, $200 million financing deal with Royal Gold provides immediate capital to advance the mine through permitting and infrastructure development.

These government-backed protections create a nearly insurmountable legal and financial barrier for Maikiuants' resistance efforts, as the company operates under regulatory stability guarantees that prioritize corporate interests over Indigenous territorial rights. Ecuador is positioned to collect billions of dollars in tax revenue from decades of extraction while the community faces displacement, environmental destruction, and the dismantling of their way of life with limited legal recourse to stop it.

The Antun family visits in their kitchen in Maikiuants.

At 28, Marcos Ankuash has spent his entire adult life defending Maikiuants' ancestral territory. The question that haunts him daily is whether he'll be able to build a life on his ancestral lands—whether his future wife and children will inherit forests and rivers, or contaminated wastelands. For Ankuash and the youth he represents, the mining company's presence isn't an abstraction, but an existential threat to everything their people have protected for generations. He's determined not to be the generation that loses it all.

"Our territory isn't for sale. It's priceless because the territory is life. It's sacred, it's the heart of the earth," says Ankuash. "I understand that the situation for fighting a big monster is quite complicated, but we have the strength of nature from our creator, with the spirit of destiny. Everything one sets out to do can be achieved by working well in the long term, taking a slow but sure step. And that's the strategic way one can fight: not today, not tomorrow, but in the long term."

“We are ancient peoples. We are a people who have territory. The territory is life for us. And that is why I invite the world to become aware of the destruction of the Amazon, of the foreign extractive activities taking place here in the territory, and to reflect deeply on all the extractive companies that are here in my territory,” says Ankuash.

A sunset in Maikiuants territory.

Ultimately, Chup sees the world’s relentless extraction of resources and the environmental destruction it leaves behind as a form of brainwashing—one his community has thus far resisted falling into. “The naive people, as I would call them, lend themselves to it. They provide services to the companies and get used to fascism, so all of society starts fighting over economics. But it doesn't realize how important the land is as a resource. And then one becomes smaller, more dependent, and less free. It leans more towards modern slavery,” he says.

Chup holds onto hope for a future where his community can return to life as it was before the company arrived—even as they face down a multimillion-dollar mining operation with the full backing of the Ecuadorian state. "If the company withdraws from the territory, I'm sure it will take some time, but we will return. Once again, we will regain the trust we once shared. But as long as the company remains in the territory, this will continue to create tension among the families."

Cultural Survival repeatedly attempted to contact Solaris Resources and Ecuadorian governmental officials for comment but received no response.

--Brandi Morin (Cree/Iroquois/French) is an award-winning journalist reporting on human rights issues from an Indigenous perspective.

Top photo: Hilda Antun prepares dinner in her kitchen in Maikiuants.

All photos by Brandi Morin.