Image courtesy of mn.gov.

By Freya Abbas

On November 30, 2020, Governor Tim Walz of Minnesota gave the greenlight to Enbridge, a Canadian energy company, to begin work on the Line 3 Replacement Pipeline which endangers Minnesota’s wetlands and waterways. Walz’s decision was heavily criticized as Enbridge was responsible for the largest inland oil spill in U.S. history in 2010, known as the Kalamazoo River diluted bitumen spill, which contaminated the lands of the Nottawaseppi people and has not been cleaned up to this day even after $1 billion was spent on the effort.

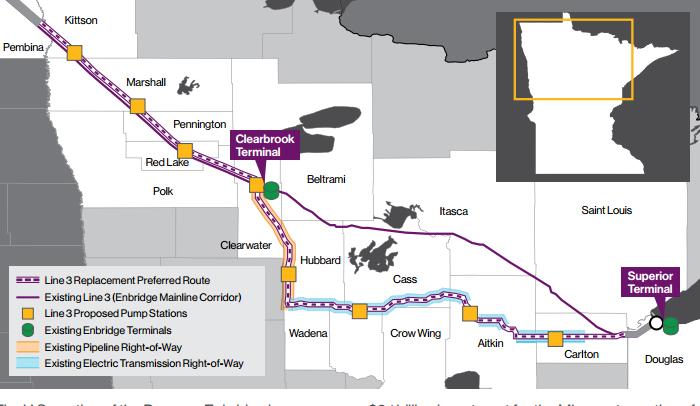

The Line 3 replacement pipeline was proposed by Enbridge in 2014 and is one of the largest projects of its kind in North America and the largest in the company’s history, with a $C5.3 billion component in Canada and $US2.9 billion American component. It is expected to carry more than 750,000 barrels of tar sands oil a day from Hardisty, Alberta to Superior, Wisconsin. This is a distance covering over 1000 miles that will run through wetlands with wild rice beds that Anishinaabe people depend on for food. The pipeline has faced legal opposition from three Anishinaabe communities including the Red Lake Nation, White Earth Band of Ojibwe, and Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe. These communities along with environmental organizations have launched direct action against the Walz administration. Activists have chained themselves to heavy equipment, locked themselves inside a section of a pipe, blockaded roads and sat in trees to prevent them from being cut down. A sit-in protest was organized in the path of the construction in December 2020.

In addition to harming wild rice beds, the Line 3 Replacement Pipeline will threaten 800 wetlands and 200 waterways, increase the spread of COVID-19 by bringing in thousands of out-of-state workers, and violate U.S. treaties signed from 1854-67. The pipeline continues to be challenged both in court and on the frontlines, even with subzero temperatures in Minnesota. Financial campaigns such as Stop the Money Pipeline are also encouraging banks to divest from the pipeline.

Tara Houska (Couchiching First Nation Anishinaabe) is an attorney who has been fighting against Line 3 for seven years and has raised awareness about the environmental impact of the pipeline as well as the potential threat to her culture. She says “If built, Line 3, a massive toxic tar sands pipeline, would destroy the sacred wild rice beds my people depend on for food, our culture and our way of life.” The pipeline would also contribute as much as 50 new coal-fired power plants to the ongoing global climate disaster. Since this plan is for a replacement pipeline, the old pipeline will be abandoned as-is. This means that Minnesota farms, homes, churches, and wild rice beds may be contaminated with oil, rust and chemicals from the old pipeline.

Enbridge is currently lobbying government agencies to allow them to avoid the responsibility of cleaning up the old pipe. The total CO2 emissions from the pipeline in one year will be equivalent to the emissions of 16-18 million cars and has an estimated cost to society of $287 billion in climate change related damage. Landowners and the general public in Minnesota are fighting against Line 3, but the most effective forms of lobbying against the pipeline so far have been from Anishinaabe communities.

The harsh weather conditions have not deterred Anishinaabe Water Protectors in northern Minnesota from taking direct action against the pipeline. In December 2020, two Water Protectors chained themselves to a truck carrying supplies to the Willow River crossing of the Line 3 pipeline. In January 2021, two protectors were arrested for obstructing construction after locking themselves inside a section of the pipe, facing charges of trespassing. The entrances to construction sites were blockaded. Activists have occupied trees, living in them while heavy machinery operated below. Twenty-two people were arrested in total near Palisade, Minnesota at a Line 3 construction site. Dawn Goodwin, a member of Indigenous Environmental Network, explains why so many are determined to stop Line 3, saying,“We are left with no choice but to put our bodies on the line to stop Line 3 and protect the water for our future generations.” She also points out that the pipeline violates several treaties with Anishinaabe people, saying “Treaties are the supreme law of the land!”

Goodwin called attention to the treaty violations posed by the Line 3 replacement project as not many are aware of them. In Canada, Line 3 crosses territory of Treaty 1, 2, 4, 6 and 7 as well as the territories of many Nations who did not sign treaties. Over 90% of the project is being built on private land. Treaties protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples to hunt, fish, gather, travel and hold ceremony on their land. In the U.S, the government has a responsibility to honor these treaties, especially by protecting areas of wild rice as outlined in the 1855 treaty.

There is also a growing concern that the pipeline will increase the spread of COVID-19 as thousands of out-of-state workers will be brought in to construction sites, and Indigenous Peoples are already vulnerable to the virus because of lack of access to healthcare resources. Enbridge says it is testing its workers every two weeks and is closely monitoring the spread of COVID-19, but people in rural Manitoba are still concerned about the potential for spread if workers interact with anyone in surrounding communities.

Direct action is not the only way that Indigenous Peoples and environmental activists are fighting against Line 3. Divestment campaigns like Stop the Money pipeline are encouraging banks to avoid renewing their support of Enbridge. On March 31st, five banks (JPMorgan Chase, Citi, Bank of America, TD (Canada), and Union Bank/MUFG (US/Japan) will have to make the decision of whether or not to withdraw their support from Enbridge. Stop the Money Pipeline encourages people to call, email, leave negative reviews on bank sites or send calendar invites to bank CEOs to alert them of the consequences of their decision. Their goal is to get one bank to walk away, which would force Enbridge to look for someone else to sponsor them. The divestment campaign was inspired by a Norwegian pension fund which withdrew from the Dakota Access Pipeline, thanks to pressure from Saami activists.

The environmental risks of the Line 3 replacement project as well as the threat to Indigenous cultures is setting the state of Minnesota back when it comes to its promises and commitments towards Indigenous peoples. Earlier in the year, Governor Tim Walz and Lieutenant Governor Peggy Flanagan attended a memorial for the Dakota 38 execution, during which they took the time to acknowledge how the state must respect Indigenous peoples and form a better relationship in the future. Flanagan said “While we can’t undo over 150 years of trauma inflicted on Native people at the hands of the state government, we can work to do everything possible to ensure that Native people are seen, heard and valued today.” Many Anishinaabe communities are struggling to have their concerns seen and heard by the state. Some have challenged Enbridge in court, through direct action, and through divestment campaigns as the pipeline violates several treaties and threatens wild rice beds.

Anishinaabe water protectors are fighting for the continuation of their culture, for future generations, as well as for the environment. They have also prepared many resources, such as a petition site to email bank CEOs and a fact sheet providing information on the pipeline designed to be shared widely, making it easy for anyone to get involved in the fight against Line 3. The movement started by Anishinaabe land defenders is relying on social media to gain public support, and the need for donations and spreading of awareness is urgent.