By Alexandra Carraher-Kang

After its first confirmed case on March 17, 2020, Navajo Nation was hit hard by COVID-19. Occupying 27,000 square miles, or just larger than the land area of West Virginia, Navajo Nation has the third-highest infection rate in the United States, with New York and New Jersey holding the two highest infection rates. As of April 25, there were 1637 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 59 deaths, marking an increase of 97 cases and 1 death over the day before. By that time, 9660 total tests had been conducted, with 7393 negative results. Put differently, almost 25 percent of those tested for COVID-19 tested positive. As a community which looks to its elders as sources of knowledge and culture, the coronavirus is particularly threatening for Navajo Nation.

The rapid rise in cases, though, can be partially attributed to an increase in testing. The Navajo Nation is leading in its rapid response to make testing available. “We expected to see higher numbers because more people are being tested. Having more people being tested is a good thing, and it helps to identify people who need to isolate themselves,” explained Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez in a press release. However, although rates of testing has been better than in many areas, in many ways the Navajo Nation is disproportionately at risk for deep impact of the virus, as a result of structural inequalities stemming from centuries of colonization and marginalization: the Nation lacks adequate running water, electricity, wifi, healthcare infrastructure. These combined with ongoing inattention from the federal government are all factors that have worsened the crisis for the 175,000 or so citizens of the Navajo Nation living on reservation lands. As Navajo Council Delegate Amber Crotty explained in an interview with Democracy Now, “It’s just shedding light on the disparities that have already existed and also the lack of federal funding to meet the demand of the health needs.”

One of the most pressing issues Navajo Nation is facing is lack of hospital space and sufficient equipment—for the 175,000 people residents of Navajo Nation, there are only about 400 hospital beds and 46 ICU beds. In addition, many living in Navajo Nation are far away from hospitals and other kinds of essential services. Doctor Heather Kovich says, “the virus landed in the middle of the reservation and exploded outward, from a remote region with an emergency department but no hospital. Many patients were transferred 100 miles east to our facility, but others were sent equally far in the opposite direction. Some were transported south to Albuquerque or Phoenix. Over the ensuing weeks, these families have had sick and dead members spread along an 800-mile circuit.”

In addition to living far distances from health services, many residents of Navajo Nation also have to travel great distances for groceries and clean water. There are only 13 grocery stores in all of Navajo Nation, which means that many have to drive long distances or carpool to pick up items. One man, Nelvin Clitso, believes he contracted COVID-19 from someone who gave him a ride home from the grocery store. Moreover, given that almost one-third of Navajo Nation residents lack running water or electricity, following advice about hand-washing and other sanitary measures is almost impossible unless residents travel every day to get water. In the words of Emma Robbins, Navajo activist and artist, “one of the hardest things right now is being able to wash your hands on the Navajo nation. If you don’t have hot and cold running water and access to soap, that’s extremely difficult... when people go out to haul water, whether that’s from stores or watering points, they’re also exposing themselves to others.”

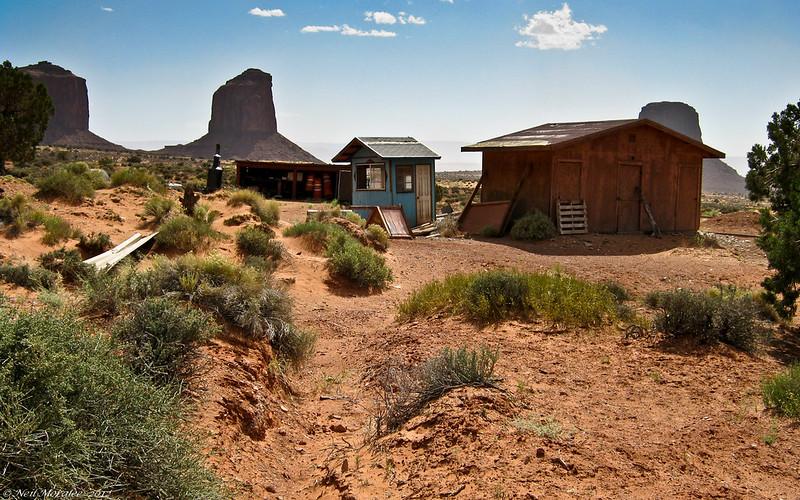

While many across the world have shifted work and school online to combat the coronavirus, many members of Navajo Nation are unable to do so. First, only 40 percent of homes have internet access. Spencer Singer, principal at Monument Valley High School in Utah, said, “there’s a lot of kids that don’t even have electricity at home.” As such, distance learning is almost impossible, and although Utah schools have ordered hotspots for families to use, only those living close enough to cell towers will be able to access the Internet. When the per capita income of those living in Navajo Nation is less than $11,000, paying for the Internet each month isn’t feasible for many. One Navajo woman, Celia Black, told NPR that her family stopped paying for the Internet because of cost, but now this poses issues for her family members studying at home. “The oldest one is more into her grades,” she said, “but she’s having a hard time because the Wi-Fi [is] not here.” Although her family was sent Chromebooks by the school, her family still needs to drive to the high school parking lot every day for Internet access.

Given that phones are now used as a primary tool to conduct contact tracing, the method has proven difficult in Navajo Nation, as many people do not own phones[1] . Moreover, many people live far apart from each other, which entails driving large distances for any contact tracing teams. As such, the strike teams utilized in other parts of the country are not as effective—Navajo Nation is large and rural, with residents spread out and relatively disconnected from the grid.

The federal government’s response to this ongoing crisis in Navajo Nation has been virtually nonexistent. First, the people of Navajo Nation, much like the rest of the country, were lied to. To quote Clitso, who disobeyed Navajo Nation’s stay-at-home order, “I wasn’t listening to whatever the newspaper or the news were saying to stay home..I thought it was just like Donald Trump was saying when that first coronavirus hit, he was saying that it was just only a hoax and I believed that.”

The $8 billion for Tribes authorized by the federal government (out of the $3 trillion relief package), in addition to being nowhere near enough, also comes with many caveats, such as grant applications. Nez has sued the federal government, arguing that the relief money is too low. “We are United States citizens but we’re not treated like that,” he said. “We once again have been forgotten by our own government.” Bill Richardson, the former governor of New Mexico, has also commented on the federal government’s inaction. “The federal government has the responsibility to provide the infrastructure to make humanitarian deliveries happen, but they don’t do it,” he stated.

In addition to issues of access to resources and federal support, members of Navajo Nation have also been subject to coronavirus-related racism. In Page, AZ, one resident was arrested for his facebook post, which read “Danger Danger if you see these Navajo anywhere call the police or shoot to kill these Navajo are 100% infected with the Coronavirus and need to be stopped.”

In the face of insufficient response from the federal government, many have stepped up to help Navajo Nation. Mutual aid funds have been established to support rural families in addition to many other relief efforts. “We’re stepping up for the community members at a time that is so crucial,” said Kim Smith, a Navajo woman running a relief operation. “And that’s what we’re here for, ultimately, as young people, to be able to sacrifice ourselves, sacrifice our well-being, so that more of our people don’t get sick. And the reality is that our ancestors sacrificed so much more for us to continue to be here.”

Pete Sands, a member of Navajo Nation in Utah, gathered a team of volunteers to help Utah Diné community members, and with partner Utah Navajo Health System Inc., he and his team conduct grocery runs, collect firewood, and offer support to the wider Diné community. “[The health system] allocated money for me to buy supplies and groceries for people in the community and for elders,” he said. “For the firewood, same way, we get it from donations. Some of it comes from my own pocket but most of it comes from donations.” However, despite having a small army of volunteers at the ready, making deliveries alone is often the safest option; Sands visits the eldery “most of the time by myself because we don’t want to risk any type of exposure...It’s secluded and not many people visit them...So, when I come by, they sit down and I talk with them—just really explain what the coronavirus is and why they have to stay home.”

Tanya Tohtsoni is currently serving as a nurse on the frontlines in Navajo Nation, overseeing the COVID-19 unit at the Northern Navajo Medical Center in Shiprock, NM. “In my nursing career, I want to continue to provide assistance to my native Diné people,” she told Navajo Times, especially because “working in a rural area, I see there are limited resources.”

“I have gained strength in my Navajo upbringing and I’m blessed to have experienced growing up on the reservation...I believe my experiences growing up Navajo, both challenges and opportunities, shape who I am along with my Christian faith.”

Another initiative, the Navajo & Hopi Families COVID-19 Relief Fund, has already raised over $1 million. One donor, Native Hawai’ian actor Jason Momoa, sent 1,540 cases of water from his company, Mananalu Pure Water, to Tuba City after learning about the Relief Fund. Ethel Branch, former Navajo Nation Attorney General and head of the Relief Fund, explained to KNAU, “I was really, really really concerned about elders who live in remote areas primarily who wouldn’t have been exposed otherwise except for coming to town to go shopping.”

Offering support from the other side of the country are the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI). In addition to sending 5,000 N95 masks to the reservation, the EBCI council, on April 23, approved up to $100,000 in funds for the medical and community needs of Navajo Nation. Principal Chief Richard G. Sneed told One Feather, “We are blessed to not have many active cases in our community, and we are blessed to have the resources necessary to share with those not as fortunate as us. The Navajo Nation needs our help, and it is our duty to provide it.”

The relief from members of Navajo Nation and other Indigenous communities has been a massive source of strength and solidarity. In Branch’s words, “It’s just so heartening and inspiring and invigorating to see how much people care at all levels, whether it’s the donors who are giving money and then it’s also just so amazing to work with these volunteers who are throwing themselves entirely into this effort. And for me it just feels personally rewarding to be able to do something rather than just watch this happen and feel helpless in the face of this situation.”

Navajo Nation has imposed a weekend curfew for the last three weekends of April in hopes to curb the spread of the virus. Although it was anticipated to end on April 26, the 57-hour weekend curfews from 8pm Friday to 5am Monday have been extended until May 17, along with other measures such as face coverings, the closing of non-essential businesses, and nightly curfews. Meanwhile, three temporary hospitals are currently being built by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers. Nez said, “We’re not letting our guard now—now is not the time. We’re seeing a slight flattening of the curve, but we have to remain vigilant.” Cases in Navajo Nation are expected to peak in mid-May, but Nez said, “we’re preparing for a worst-case scenario.”