By John McPhaul

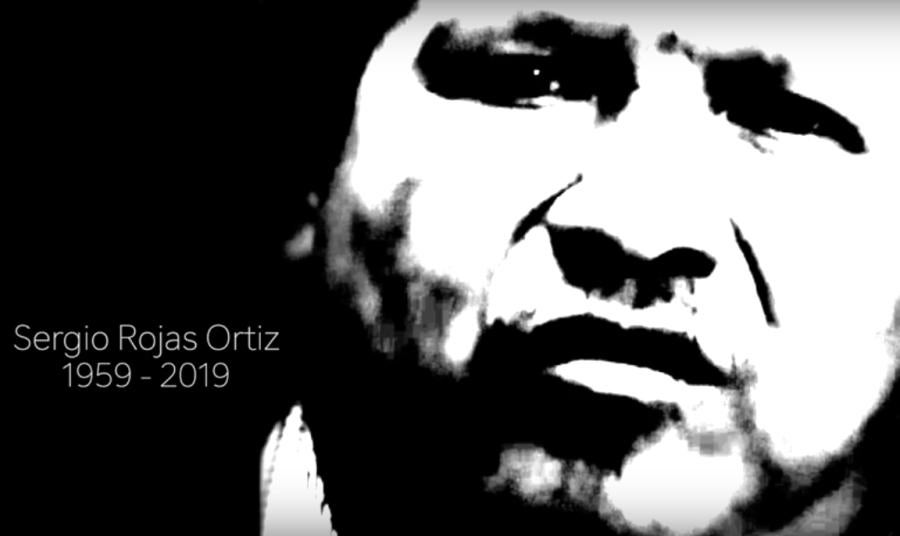

Fear still reigns in Indigenous country after the murder of Bribri Indigenous leader Sergio Rojas, who was shot and killed on March 18, 2019, while he slept in the small village of Yeri in the Salitre Indigenous Territory, in southwestern Costa Rica.

Indigenous leaders are hopeful that the crime will soon be solved despite the worries of continued violence."Of course we are nervous, but we are also confident in the Costa Rican State which is giving us a lot of cooperation," said Felipe Figueroa, 55, secretary of the Ditso Iriria Ajkinuk Wakpa Council of Salitre which is seeking to recover land in Indigenous territories which are in the hands of non-Indigenous people.

The Costa Rican Indigenous Law was passed in 1977 setting up 24 Indigenous Territories, but the government failed to compensate many landowners in the territories and since then many more non-Indigenous have squatted on the land with nothing more than a bill of sale to back their claim. Officials estimate that as much as 75 percent of Indigenous land is in non-Indigenous hands. Figueroa said that the movement to reclaim land for the Indigenous will continue despite Rojas' murder. "We will keep going," he said. "It will probably take another ten years.”

In 2010, Rojas, 59, emerged as a leader among the Bribri. Leading an effort by Indigenous Peoples to reclaim land in the Salitre Indigenous Territory, he had garnered the enmity of non-Indigenous land-holders. However, a former government official, the Minister of Information for former President Luis Guillermo Solis Mauricio Herrera, recently argued that division existed within the Bribri community, pointing to some Indigenous community members who say Rojas has questioned their land claims as Bribri since the ethnic group hands down its membership matrilineally, which Rojas disputed. To his credit, Solis, in March 2018, signed the General Mechanism of Consultation with Indigenous Peoples, intended in part to address the land disputes in Indigenous territories.

Meanwhile, Costa Rica's Teletica Channel 7 reported on March 27, 2019, that prosecutors are still trying to determine the whereabouts of around $1 million in forest preservation funds entrusted to Rojas, as director of the Salitre Development Association. Prosecutors brought charges against Rojas and 10 associates alleging that they were reporting having turned the government funds over to fellow Indigenous for preserving forest land, but the supposed beneficiaries maintained they never received the money. About two years ago, Rojas spent seven months in preventative detention on embezzlement charges. The National Distance University anthropologist Amilcar Castañeda defended Rojas at the time, saying that a disorder in the bookkeeping in the nation-wide forestry project is common.

Marcos Guevara, a University of Costa Rica anthropologist and an expert in Costa Rican Indigenous affairs who had known Rojas for 30 years, said that Rojas did not have any trappings of ill-gotten gains. “He always said he was innocent and one of his attorneys, Ruben Chacon, whom I have known for a long time, also believed in his innocence,” said Guevara. “He did not have a luxurious house, more like a humble home, nothing that would permit you to say that he had profited with a lot of money. Nor did he have objects of great value and, as far as I know, no bank accounts full of money.”

While the TV report left the impression that the murder motive was more complicated than appears on the surface, the criminalization of Indigenous leaders is a common strategy used by governments across Latin America to discredit Indigenous activism.

Samuel Delgado Rojas, 35, a Bribri Salitre resident and nephew of Sergio Rojas said that the principal suspects are non-Indigenous. “They have a list of suspects among non-Indigenous people who live here and the OIJ (judicial police force) and the Public Ministry (state prosecutors) are making a great effort to solve the crime,” said Delgado, “I have a lot of confidence that they will solve it. Perhaps not in the short term, but they will solve it.” Delgado also said the atmosphere in the community remains very tense.“Calm hasn’t returned for us,” he said.

Delgado stated he is happy to be among the Bribri who were able to recuperate land under the leadership of Sergio Rojas, though he says that life is difficult with a constant state of fear because of the conflict with non-Indigenous settlers. “You can't feel safe. You always walk afraid in the street. You can’t be tranquil going about your daily business or going to meetings,” said Delgado.

Xinia Zúniga, a social researcher who has extensively studied the situation in Salitre, told Channel 7 that she has maintained constant contact with the residents and that they report that last week during the night they have continued to hear shots in the jungle, believed to be clear intimidation of potential witnesses or informants.

Guevara commented on March 22, 2019, that he is also concerned about a possible escalation of violence if the murder of Rojas is not solved soon. "There is a lot of concern for the lives of other people because if other non-Indigenous people become emboldened with the murder of Sergio, they will attack others [Indigenous leaders involved in Indigenous land reclamation] from Salitre and other communities," said Guevara. " I trust that this government will take actions to protect the recuperators and that justice will find those responsible, otherwise the violence will undoubtedly escalate. We are dismayed and very angry and sad about what happened. We were working on a project in Salitre with several organizations and also with Sergio."

Castañeda said that if the perpetrators thought that they would stop the Indigenous land reclamation movement by eliminating the 59-year-old Rojas, they were mistaken."There is a popular saying 'the honeycomb has been touched, and the bees are angry', there is much consternation throughout the country, if the objective was to terrorize the Indigenous population, and particularly the land recoveries, stop the fight for land, I believe that the shot backfired," said Castañeda. "The people have unified and renewed their commitment to continue and deepen with the struggles for land and Indigenous rights. The Costa Rican State is obliged not only to answer for the murder of Sergio Rojas, but also to answer the basic issue, the problems of the land. And this has been positioned alongside the death of Sergio."

In 2015, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights ordered precautionary measures be taken to protect the Bribri who were trying to recover land guaranteed to them by the 1977 Indigenous Law and who were subjected to violent attacks by the non-Indigenous occupiers of the land. Conflicts arose when some who held land title predating the Indigenous Law were never compensated.

The movement led by Rojas to reclaim Indigenous land managed to recover 75 percent of the land in the Salitre territory, according to reports. In the 24 Indigenous reserves claimed by eight Indigenous Peoples of Costa Rica's 106,000 Indigenous population, 75 percent is occupied by non-Indigenous settlers.

On the afternoon before his murder, Sergio Rojas had accompanied a Bribri man to file a complaint in Buenos Aires, who, along with one other Bribri man, were victims of an attempted homicide. Prosecutors from the Adjunct Prosecutor of Indigenous Affairs are now appealing a Buenos Aires de Puntarenas judge’s ruling freeing a father and son accused of attempted homicide against two Indigenous Bribri that Sergio Rojas had accompanied. The duo was freed on the condition that they wear electronic tracking anklets and that they stay away from the Salitre Indigenous Territory. According to the prosecutor's office, they shot at the two Bribri who were able to escape harm by hiding behind rocks and trees.

--John McPhaul is a Costa Rican-American freelance writer based in San Juan, Puerto Rico.