By Dev Kumar Sunuwar (Koĩts-Sunuwar, CS Staff)

Human trafficking is one of the most difficult issues to address in Nepal. It is a purposefully hidden practice, affecting and exploiting thousands of women, adolescent girls, and children. But despite its invisible nature, it abundantly shows that Indigenous women and girls are disproportionately affected by human trafficking and represent almost 70 percent of the cases.

According to Nepal Tamang Mahila Ghedung, an umbrella organization of Tamang Indigenous women, and partner organization of Cultural Survival, there is no exact figure on the ethnic and caste composition of women and girls trafficked to India and other countries. The percentage of caste and ethnicities of women and girls rescued by the Nepali government and civil society is the only statistic available to go by, and Indigenous women and girls make up the majority of the people trafficked and exploited. Citing the internal assessment of caste and ethnic-wise survivors, two NGOs, Shakti Samuha (an organization of survivors of women trafficked) and Maiti Nepal (an NGO long fighting against trafficking), showed that 70 percent of those rescued were from Indigenous communities.

In July 2011, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women issued a concluding observation raising concerns about the lack of specific data on trafficking of women and girls, the lack of effective implementation of the Human Trafficking and Transportation Act of 2007, the persistence of sexual exploitation and persistence of the root causes of trafficking and prostitution, including poverty in Nepal. The Committee also urged the Nepali government to fully implement Article 6 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) through collecting and analyzing data on all aspects of trafficking and prostitution disaggregated by age, sex, and country of origin in order to identify the trends, to implement the Human Trafficking and Transportation Act of 2007 to ensure that perpetrators are punished and victims adequately protected, assisted and provided shelter, to strengthen preventive measures aimed at improving the economic situation of girls and women, to provide gainful employment and other resources to eliminate their vulnerability to traffickers including strengthening efforts at international, regional and bilateral cooperation with countries of origin and transit to address more effectively the causes of trafficking and improve prevention of trafficking through information exchange.

Disaggregated data gathered on caste and ethnicity was released in 2019 by the National Human Rights Commission, a national Nepali human rights body, which shows that 49 percent, a majority of trafficked women survivors are Indigenous nationalities, followed by Dalit at 15 percent. Madhesis account for 6 percent and other ethnicities constitute the remaining 29 percent. Indigenous Peoples, Dalits, and Madhesis are the most socially, politically, and economically marginalized and excluded communities in Nepal. Traffickers intentionally do not target one particular social group. But women and girls from minority groups including Indigenous Peoples are vulnerable to trafficking as they belong to socially, politically, and economically marginalized communities.

“Indigenous women and girls are often targeted by traffickers because they grow up in poverty. They have no good clothes to wear and not adequate food to eat. So they can be easily lured with fake promises of good employment,” says Mayalu Lama, Secretary of Nepal Tamang Mahila Ghedung, who worked for over a decade in a project combating trafficking in persons in Kavre District. “Besides poverty, their lack of access to education, information, employment and services are other reasons why trafficking is increasing in recent days. Firstly, girls from minority groups can hardly get enrolled in schools, even if they are, they drop out before reaching higher level due to poor academic progress in exams.”

According to a report released by the National Human Rights Commission, in the year 2019 alone as many as 15,000 women and girls including 500 children were trafficked, and these are just the known cases. It is estimated that more than 17,000 women and girls are trafficked every year by strangers, neighbors and families to India for sexual exploitation, also to work in circuses, as domestic workers, in forced labor, or even are made to give up their organs. Many are often lured with promises of well-paying jobs in foreign employment or with fake marriages. These are the common traps used by traffickers.

Though survivors inferred that traffickers also used threats, drugs or medicines, the main modus operandi of human trafficking is promise of a better, more prosperous life. Many women and girls are promised good employment with good salaries, prospects of higher education abroad, opportunities to travel or marriage. In reality, they end up being trafficked and raped in brothels abroad. Many fall prey to illegal organ removal in India. Still, many women and girls never cross the border rather end up in forced prostitution in one of the hundreds of singing restaurants, dance bars or massage parlors in the urban centers across Nepal. These have been the internal hub for trafficking.

According to Nepal Tamang Women Ghedung, Tamang Indigenous women and girls from the adjoining Kathmandu Valley make up the majority of the Indigenous people trafficked and exploited. Historically, Tamang women were forced to serve as courtesans and concubines to the rulers in Kathmandu, the capital city of Nepal, and today are the largest group of people affected by sex trafficking to India and other countries. Tamang women and girls, in particular, are at particular risk due to their isolation. Though Tamang communities live in areas surrounding Kathmandu Valley, they have high rates of illiteracy, little access to the outside world, and experience high levels of poverty and unemployment. But today human trafficking has been a challenge across Nepal.

Following the 2015 earthquake in Nepal, economic opportunities have been severely disrupted and the numbers of missing women and girls including children have risen sharply, with thousands of Nepalese being trafficked across the border and many more vanish with no chances of return. The cases of human trafficking are occurring in the entertainment and hospitality sector. Guidelines exist to control sexual exploitation of women workers in dance restaurants and bars, which aim to prevent sexual abuse, however a systematic study has not yet been conducted to assess how big the magnitude of the problem exists in the dubious entertainment sector.

“The cases of trafficking of women and girls have increased today due to the increased use of mobile phones and social media such as Whatsapp, Facebook, emo, TikTok, etc,” says Mayalu Lama, “social media has made it easier for traffickers to reach potential girls, connecting them through a friend request, liking or commenting on a post and finally meeting them in person.”

Women and girls often from marginalized and impoverished backgrounds are targeted by human traffickers, but there is also trafficking of men as well. Some leave home with the hope of finding jobs as domestic workers in India or Gulf countries but many have ended up being trafficked. There has been a shift in the pattern of human trafficking in Nepal with the opening borders to foreign labor migration and internal displacements caused by poverty, discrimination, and gender discrimination. Police raids in India show that the brothels now are increasingly being run out in apartments also by Nepali women who once were trafficked and sold themselves. Traffickers use Nepal’s open border with India to transport Nepali women and children to India under the guise of an “orchestra dancer.” Labor traffickers exploit women and children in domestic work in India, the Middle East, Gulf countries such Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Asian countries like Malaysia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Because of the partial ban on female domestic workers to Gulf countries, many Nepali domestic workers do not have valid work permits, and this increases their vulnerability to trafficking. There are also instances of Nepali women marrying men in China and Korea through a marriage bureau and are then forced into domestic servitude. Nepali women and girls are trafficked through Sri Lanka, Myanmar and India to third countries without proper documentation.

Commendable efforts have been made by the government and various agencies in Nepal to combat human trafficking, but there is still a need to take stronger steps to eliminate it by identifying and intervening at the root causes of what enables human trafficking rackets to thrive.

In 2011, Nepal ratified the United Nations Transnational Organized Crime Convention, the parent convention of trafficking in persons and smuggling of migrants, and acceded to Palermo Protocol, supplementing the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime on June 16, 2020, which aims to prevent, suppress, and punish trafficking in persons especially women and children. In order to make national laws consistent with these international laws relating to trafficking persons, Article 29 (3) of the 2015 Constitution of Nepal makes trafficking punishable by law, the Human Trafficking and Transportation Act of 2007, and Regulation 2008 (amended in 2020) have criminalized slavery and bonded labor, also include basic protections and remedies for victims of trafficking. The Act and Regulations provision fines and imprisonment ranging from 10 to 20 years for sex trafficking including rape, but have not yet criminalized recruitment, transportation, receipt of persons by force, fraud or coercion for the purpose of forced labor.

The government also has adopted and implemented a National Plan of Action Against Human Trafficking (2011-2021) prioritizing prevention, protection, prosecution, capacity development and coordination, cooperation, and collaboration. However, a large gap remains compared to the size of the problem. The law does not criminalize all forms of labor trafficking, transnational labor trafficking including protections for male trafficking victims. Investigations, prosecutions, and convictions of all trafficking offenses, including conduct investigations on crime into labor recruiters and labor trafficking agents are still being done on a very small scale. Moreover, there need to be coordinated efforts of interagencies of government and civil society on human trafficking at the national and district levels.

There are systems and laws in place but they largely remain inactive and ineffective in implementation on a practical level. There is an urgent need for consolidated efforts from stringent border monitors, rescue and rehabilitation initiatives, to awareness campaigns and mitigation measures undertaken jointly by the government and civil society to address the problem of trafficking with a priority of reaching vulnerable groups. And much needs to be done to curb the demand for human trafficking, this includes shifting consciousness, eliminating racism, and gender discrimination as well as elevating the status of women by building respect and promoting women’s leadership.

“There is a need to create opportunities for generating income to end poverty and unemployment, so as to increase the literacy of the marginalized communities in the remote villages, focused and stepwise plans and programs targeting excluded communities like Indigenous nationalities, Dalits, and Madesis,” says Mayalu Lama. “The government and some civil society organizations are making efforts in raising awareness but they are inadequate and awareness-raising plans and programs in the languages of Indigenous Peoples are not [yet] there.”

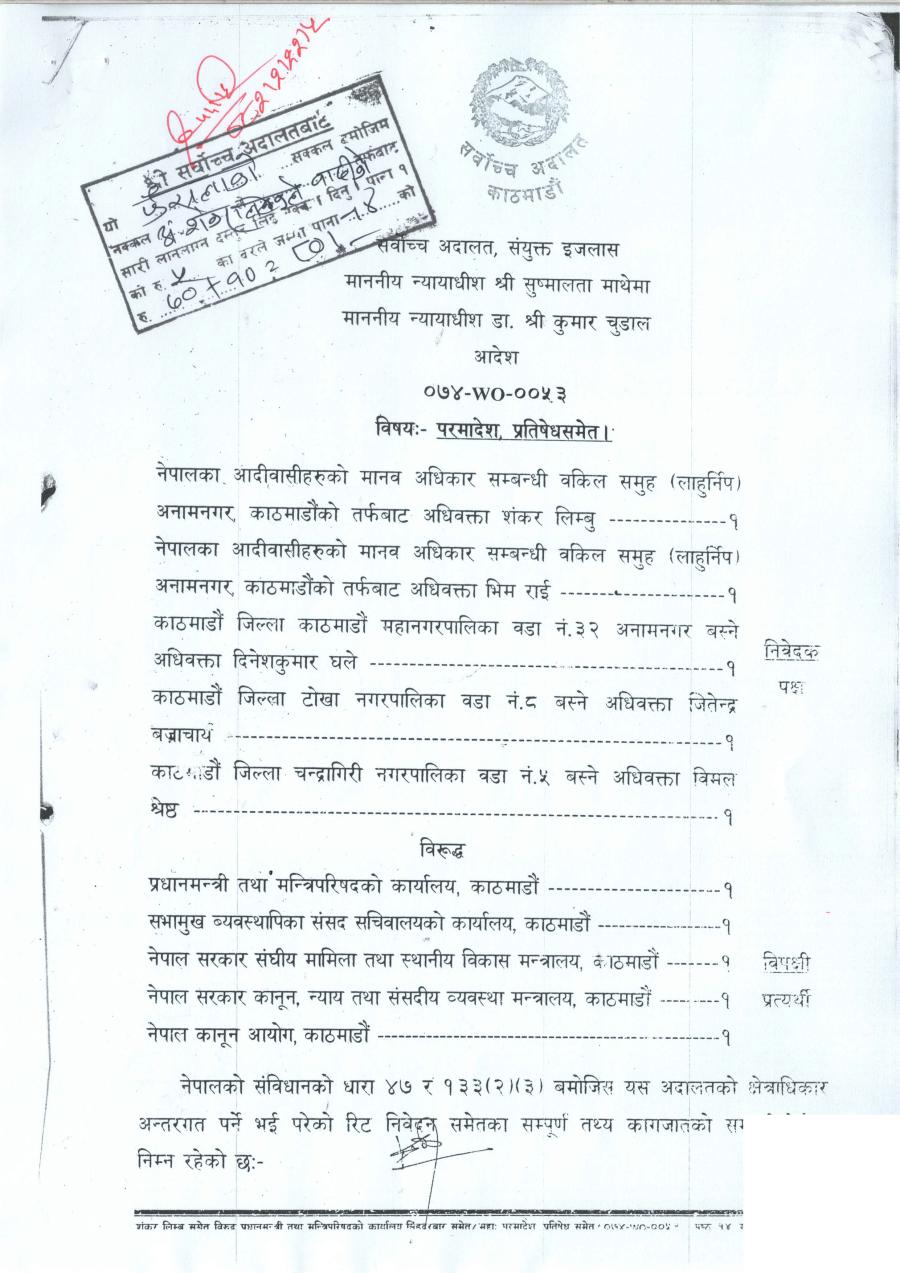

Photo: Orientation program against human trafficking, on transportation control, and safe migration organized jointly by Cultural Survival and Nepal Tamang Mahila Ghedung at Bidur, Nuwakot, on March 9, 2021.