Every year around the 23rd of June, Mixtec people from the municipality of San Juan Mixtepec gather to celebrate their patron saint. The music echoes between their respective gathering places in Oaxaca and Lamont, California.

In Oaxaca, the loudspeakers broadcast the towns of the municipality whose residents gather in the municipal city to share food, drinks, music, and a dance or several with one another.

In Lamont, the people of Mixtepec gather to share the same joy, but the loudspeakers boom out the names of the California cities and the different states where Mixtepequenses call home in the U.S.

Past, present, and future ripple across each other in Lamont and Mixtepec, as if the joyous stepping and stomping of the townspeople were calling forth from space and time their home and history as fuel for the spirit to move forward.

Spanish, English, and Tu’un Savi can be heard as overlapping murmurs throughout the event floor, drawing a mosaic of our experiences. The elders rejoice at the sound of violin chilenas as the youth do at the beats of their era.

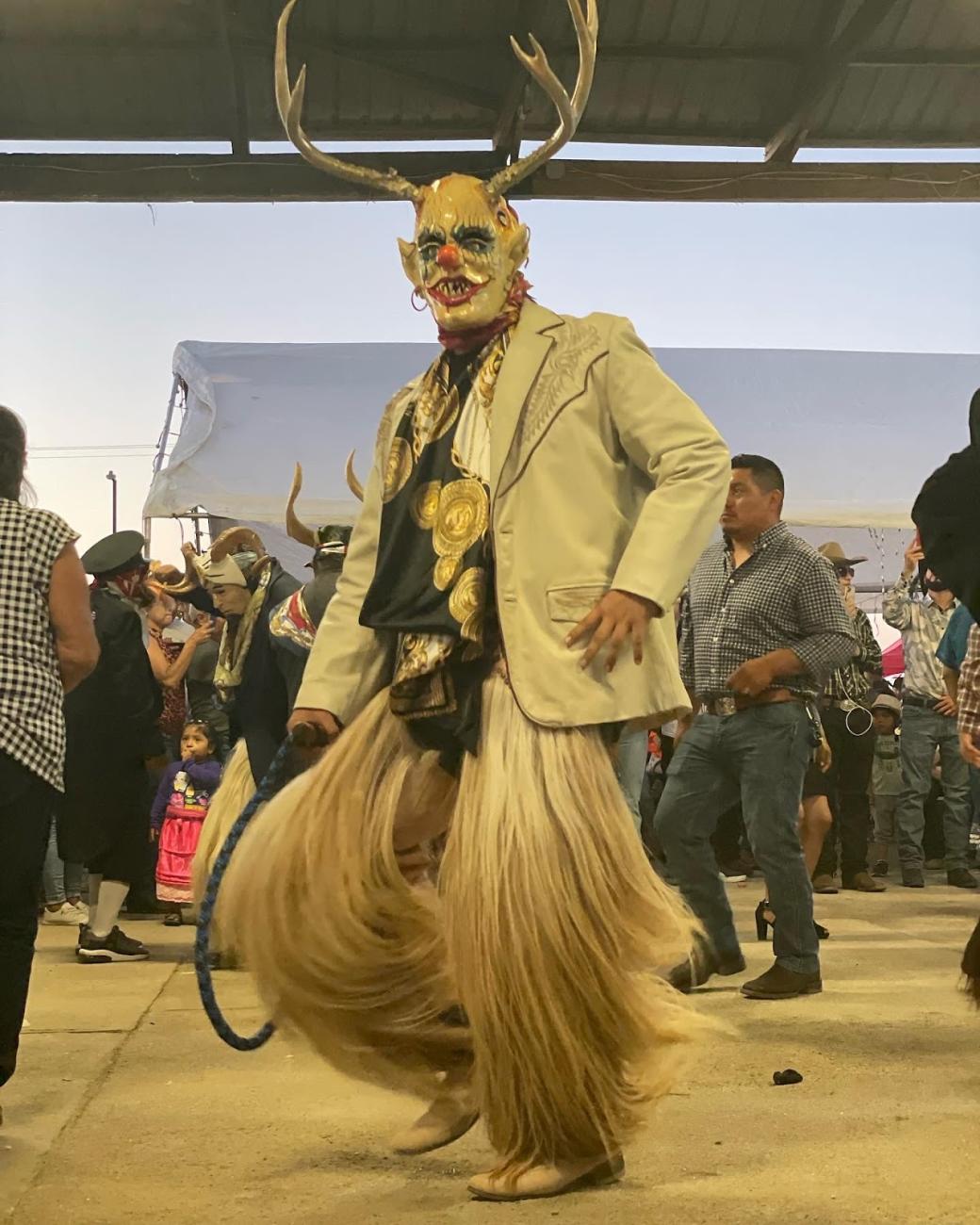

The Ña’na Chaà, costumed in military uniforms and blonde hair, dance among the Ña’na Ña’á, who are supposed to be men disguised in the dresses of the townswomen. They represent the efforts of the community to fight against the white man’s violence against the women they encountered in our homeland.

People dressed as horned beasts with whips, lassos, and chaps adorned with goat hair stomp around the dancefloor, representing the devil the Catholics brought with them to attempt to teach us how they see evil.

Families meet and catch up or reconnect. They introduce new generations and mourn past ones through conversations in the crowd, reminding us that the spirit of transformation gives and takes across life.

They make their offerings to San Juan for the communal good of the people in hopes we will see each other again in the next celebration.

La Fiesta Patronal de San Juan Mixtepec:Viko Ñuu Xnuviko

Cada año alrededor del 23 de junio los mixtecos del municipio de San Juan Mixtepec se reúnen para celebrar a su santo patrono. La música resuena entre sus respectivos lugares de reunión en Oaxaca y Lamont, California.

En Oaxaca las bocinas mencionan los pueblos del municipio cuyos habitantes se reúnen en la cabecera municipal para compartir comida, bebida, música y un baile o varios entre ellos.

De manera similar, en Lamont la gente de Mixtepec se reúne para compartir la misma alegría, pero las bocinas retumban los nombres de las ciudades de California y diferentes estados donde los mixtepequenses llaman hogar en los Estados Unidos.

Pasado, presente y futuro se entrelazan en Lamont y Mixtepec. Como si los pasos y pisoteos alegres de la gente del pueblo estuvieran llamando desde el espacio y el tiempo su hogar y su historia como energía para que el espíritu avance.

Se pueden escuchar español, inglés y tu’un savi como murmullos superpuestos sobre todo el piso del evento dibujando un mosaico de nuestras experiencias. Los mayores se alegran al son de chilenas de violín, como lo hacen los jóvenes con los sonos de su época.

Los Ña’na Chaà, gente disfrazada con uniformes militantes y cabello rubio, bailan entre los Ña’na Ña’á que se supone que son hombres disfrazados con los vestidos de las mujeres del pueblo. Representan los esfuerzos de la comunidad para luchar contra la violencia del hombre blanco sobre las mujeres que encontraron en donde ahora se asienta Mixtepec.

Personas vestidas como bestias con cuernos, con látigos, lazos y chaparreras adornadas con pelo de chivo pisan fuerte en la pista de baile; el diablo que los católicos trajeron para intentar enseñarnos cómo ven el mal.

Las familias se encuentran y hablan de cómo les ha ido desde la última vez que se vieron o se vuelven a conectar después de tantos años sin verse. Presentan a las nuevas generaciones y lamentan a las pasadas a través de conversaciones entre la multitud, recordándonos que el espíritu de transformación da y recibe en la vida.

Hacen sus ofrendas a San Juan por el bien común del pueblo con la esperanza de que nos volvamos a ver en la próxima celebración.

Cypress/Tuyuku/Ahuehuete

You are that little seed your parents brought from the homeland

an uprooted seedling

an ahuehuete away from the river

the ones seen all over la Mixteca now up that route that people follow to find their way out of poverty

following the American dream.

Ku in Tuyuku

the ones held sacred for more than 500 years now on foreign soil

Your roots sometimes have trouble remaining in the dirt

you remain as firmly planted as you can be among all the flora of this country that make you feel like you don’t belong

You stick out like a sore thumb

you question whether you are that sacred tree,

a golden poppy

an Oregonian grape

a pacific Rhododendron

an Orange blossom

a common blue violet

a saguaro

or a national Raegan rose

But you are that seed

that uprooted seedling

the ahuehuete away from the river back home.

You will hopefully still grow as tall as the ones in the region of the rain.

I hope those roots miss home enough to pull new waters

to carve out a new river

one in which new seeds can grow

where there is no need to be uprooted

where ahuehuetes are as common as the Northern wildflowers those people who crossed the sea tried to kill

The wildflowers that were here before their borders existed

when these plants were part of everyday life,

not another symbol for their states,

of how they divided this continent so they could manifest a destiny without us in it

Work/Trabajo/Chuun

The first job I worked when I moved to West L.A. from Santa Maria was in a kitchen for a dining commons at a senior living facility in Santa Monica. I was a dishwasher. I got good at it after I had to work six 15 hour shifts for 2 weeks, but for those first 2 weeks Carmela, Doña Mari, Teodoro, and Margot would help me with the dishes because I couldn’t keep up. I thanked them by helping them with their tasks if they were running behind, too. They had all worked in that kitchen for so long and showed up with more effort than what they were getting paid for.

When I was able to work faster, I’d offer to help Esteban, a chef who would teach me how to prepare the ingredients for the menu. Esteban would insist that music should be played in the kitchen; it gave him the ganas to work throughout the day. It gave us all ganas. He would mostly play banda and would slam his hand against the prep table every time a song about heartbreak would come on. He was happily married, but songs like “No Llega el Olvido,” “Dime Cantinero,” “Tu Postura,” or “Las Cosas no se Hacen Asi” are hard not to get into and a lot easier to listen to when you’re happy. Bless that man for being so patient with me when I got moved up to cook and he had to teach me everything else aside from prepping.

How we practiced reciprocity and looked out for one another in that kitchen would remind me of home: of the way family and I have learned to care after each other, of the kindness of friends and neighbors in Santa Maria and Los Angeles, of the communality that has paved the way so the people of my family’s hometown in Santa Cruz Mixtepec could flourish so far from Oaxaca. Everyone’s determination motivated by the emotion of music would remind me of the paisanas and paisanos in the strawberry fields who work with portable radios on their waists, ready for a long day under the sun. They’d remind me of the pueblo loudspeaker playing chilenas while the townspeople went about the labor in their day, and they’d remind me that throughout all these different experiences with work, we figure out pathways for joy as we push forward for more.

-- Claudio Hernandez (Na Ñuu Savi/Mixtec) is a 2022-2023 Cultural Survival Writer in Residence.