By Phoebe Farris (Powhatan-Pamunkey)

“The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans,” is the name of the current exhibition curated by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., now on display through January 15, 2024. It is also the title of the beautifully illustrated hardcover catalog with essays by Smith, heather ahtone (Choctaw/Chickasaw Nation), Shana Bushyhead Condill (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians), and a poem by former Poet Laureate, Joy Harjo (Muscogee Creek Nation).

During the invitational preview reception that featured remarks by U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Deb Halland (Laguna Pueblo), and at press events the next day, I spoke with several artists and essayists, including Smith, to gain insights about the exhibition theme, artist selection process, and the works on display.

U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith wearing her gifted blanket at “The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans” opening reception on September 21, 2023.

The catalog offers an in-depth analysis of how the artworks and artists were selected and the exhibition’s overarching theme of the land’s intrinsic importance to Native Americans. In her essay, “Sky as Place, Land as Body, Landscape as Spiritual Compass,” ahtone, who is Director of Curatorial Affairs for First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City, explains that racializing Indigenous Peoples into one group denies the uniqueness of each Tribe in their “wholistic approach to visualize a philosophical paradigm.” The colors used by one Tribe may represent different ways of knowing from another; the complex diversity of our artistic expressions and cosmological stories can not be homogenized. ahtone praises Smith for uniting such diversity into a cohesive whole, writing, “Jaune Quick-to-See Smith has brought together artists whose works share the beauty of this diversity. Smith introduces artists whose works express their love for the land as a place, the sky as a space, the cosmos as a home, and the landscape as a spiritual compass for our humanity. These works entreat us to remember our planet is not merely a resource or an asset over which humans have been given dominion. The land is our mother, and Indigenous people will do whatever is needed to protect her.”

L-R: Steven Yazzie and Linda King.

Another essay, “The Dust On Our Feet,” written by Condill, who is the Executive Director of the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, North Carolina, focuses on her conversations with Smith about how she chose intergenerational artists from various geographical regions and genders who use a wide range of mediums. Smith is interested in helping to develop a canon of Native art scholarship that reflects a Native perspective. She and Condill agree that landscape is “an extremely useful entree to the Native worldviews,” and that “Land and place are tied to all things...History-making, ceremony, cooking, and gathering are all associated with place.” Their dialogue reinforces the Native perspective that connects landscapes to the sacred world and the Native respect for land, sky, and water. The phrase “Water is Life” became popularized during the Dakota Pipeline activism, and Smith reminds us, “Water is everything. Water is everywhere. It doesn’t matter where the landscape is located, water provides life.”

L- R: Shana Bushyhead Condill (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians) one of the catalog’s essayists and the Executive Director of the Museum of the Cherokee Indian with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.

“Land/Landbase/Landscape,” written by Smith, emphasizes that Native Americans live in a holistic, circular world without horizon lines, that the natural world is our kin and that we live in a kin-centric world; our sacred spaces are not fixed locations because our “sacred space is everything around us, from the land to the sky...The reason why you sometimes don’t see a horizon line in our artwork is because this belief is part of our epistemology.” For Smith, works of art are more than beautiful objects on display. “While they may not fit into the mainstream of Euro-American perceptions of landscape, they do represent our enduring connection to land. For us, Native definitions of land/landbase/landscape are always and forever; it is the sacred land of our ancestors. We know that no matter where we go, the dust of the land carries our ancestors.”

L-R: Rose Powhatan, Linda King, and Joe Feddersen.

L-R: Rose Powhatan, Linda King, and Joe Feddersen.

As journalists, art critics, and documentary photographers we are supposed to be objective when reviewing a play, a concert, or in this case an art exhibition. But is that really possible? As humans, we have embedded or implicit biases that inform our observations, our reporting, and our critiques. For me, “The Land Carries Our Ancestors” was somewhat of a déjà vu experience. Eleven of the forty-nine artists/curators/consultants involved with the exhibition were people I had previously worked with in other exhibitions, collaborated with on conference panels, or interviewed for various publications. Seeing some of them in person for the first time in 20 years deeply affected my experience of the opening events, and I felt drawn to their works both for their aesthetics and for those personal connections.

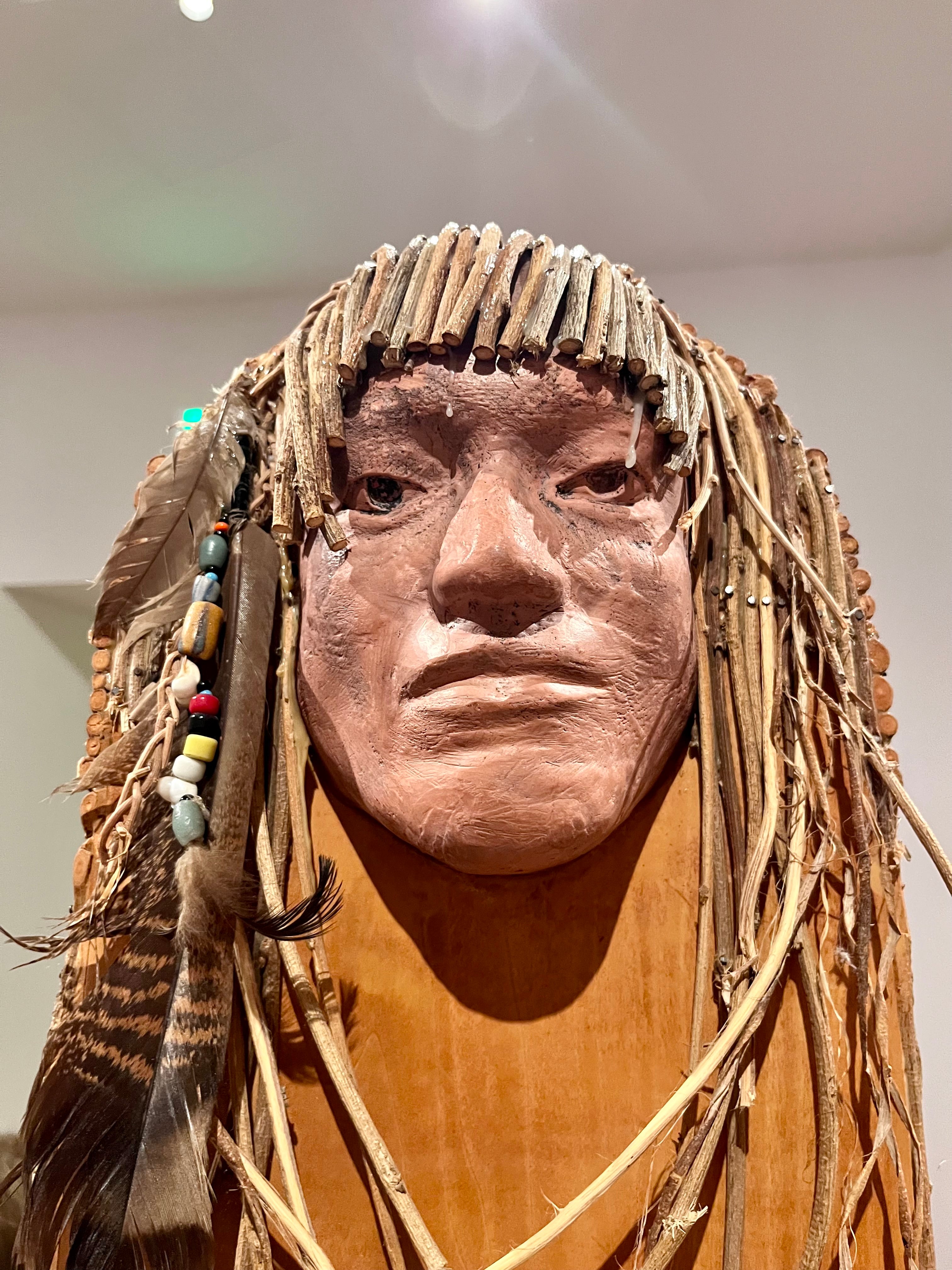

Close-up of “Fire Warrior Woman”, 2007, by Rose Powhatan.

Artists Joe Feddersen (Colville Confederated Tribes), Edgar Heap of Birds (Cheyenne and Arapaho), Linda Lomahaftewa (Hopi/Choctaw), George C. Longfish (Seneca/Tuscarora), Mario Martinez (Pascua Yaqui Tribe of Arizona), Rose Powhatan (Pamunkey/Tauxenent descent), Gail Tremblay (Onondaga/Mi’Kmaq), Kay Walking Stick (Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma), Emma Whitehorse (Dine’), Smith, and Neal Ambrose-Smith (Confederated Salish and Kootenai descent) reference their ancestral attachment to the land using such varied materials as fine art paper, metals, inks, acrylic paint, canvas, oil pastels, wood, vine, clay, feathers, 16mm film, and silver yarn, with palettes ranging from vibrant and bold to subtle earth tones to transparent, and all manner of shapes—abstractions, realistic, ephemeral, and textured— stretching the concept of land from uniquely Indigenous perspectives.

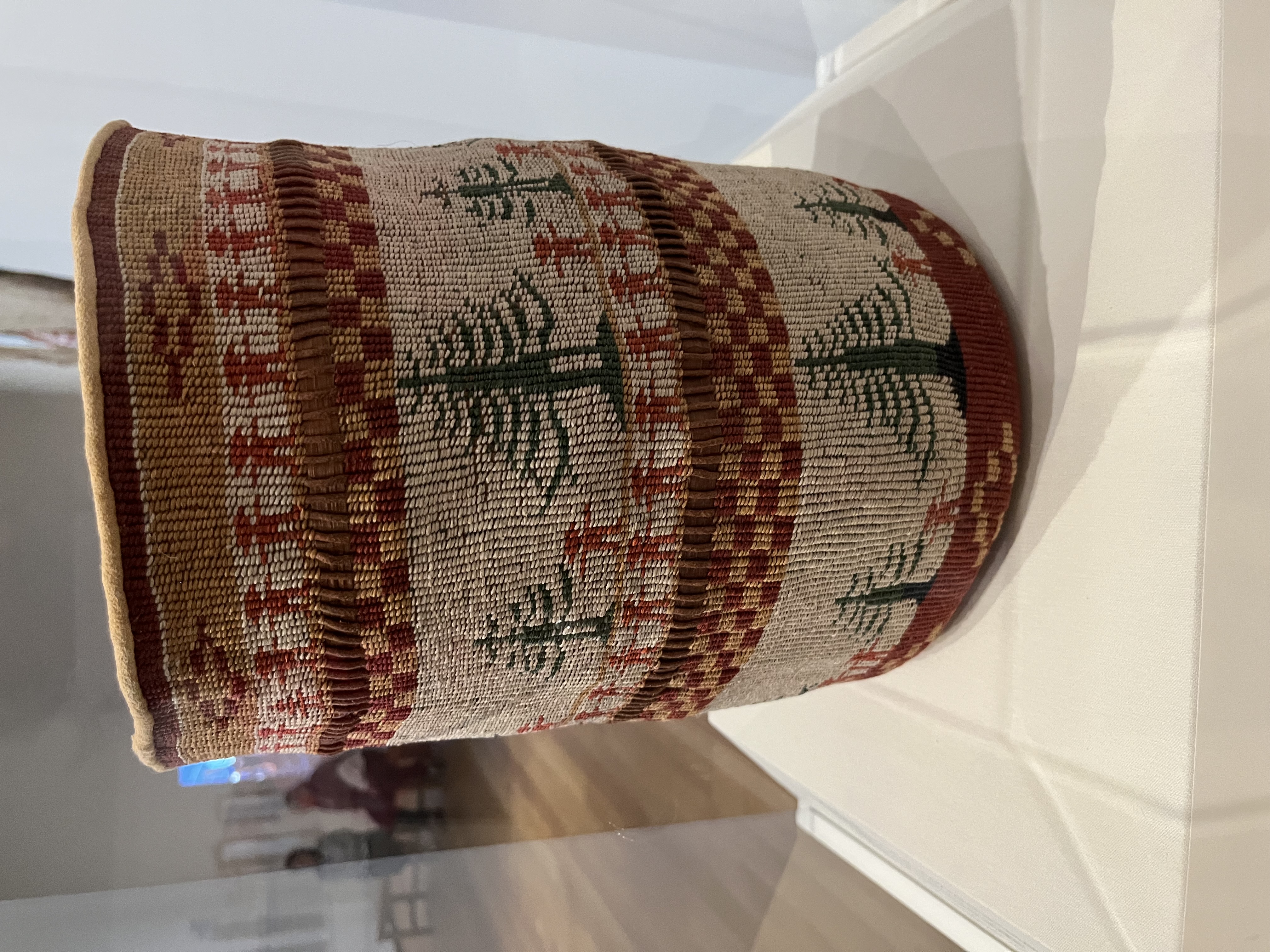

“Teaching of the Tree People”, 2018, by Linda King.

I felt particularly drawn to the work of Linda King (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes) and Steven Yazzie (Dine’/Laguna Pueblo), two artists whose art I was unfamiliar with. King’s “Teaching of the Tree People” (2018), made with waxed cotton, waxed linen, Red Cedar, and buckskin, has a quietness about it with earth tones that evoke calm in the midst of a brightly lit, crowded gallery. King believes that artistic talent is a gift from the Creator and should be shared, not owned. She says, “The cultural arts, important historical stories are handed down, shared, and maintained from past generations. When we create our own stories today, we provide a path to our future.”

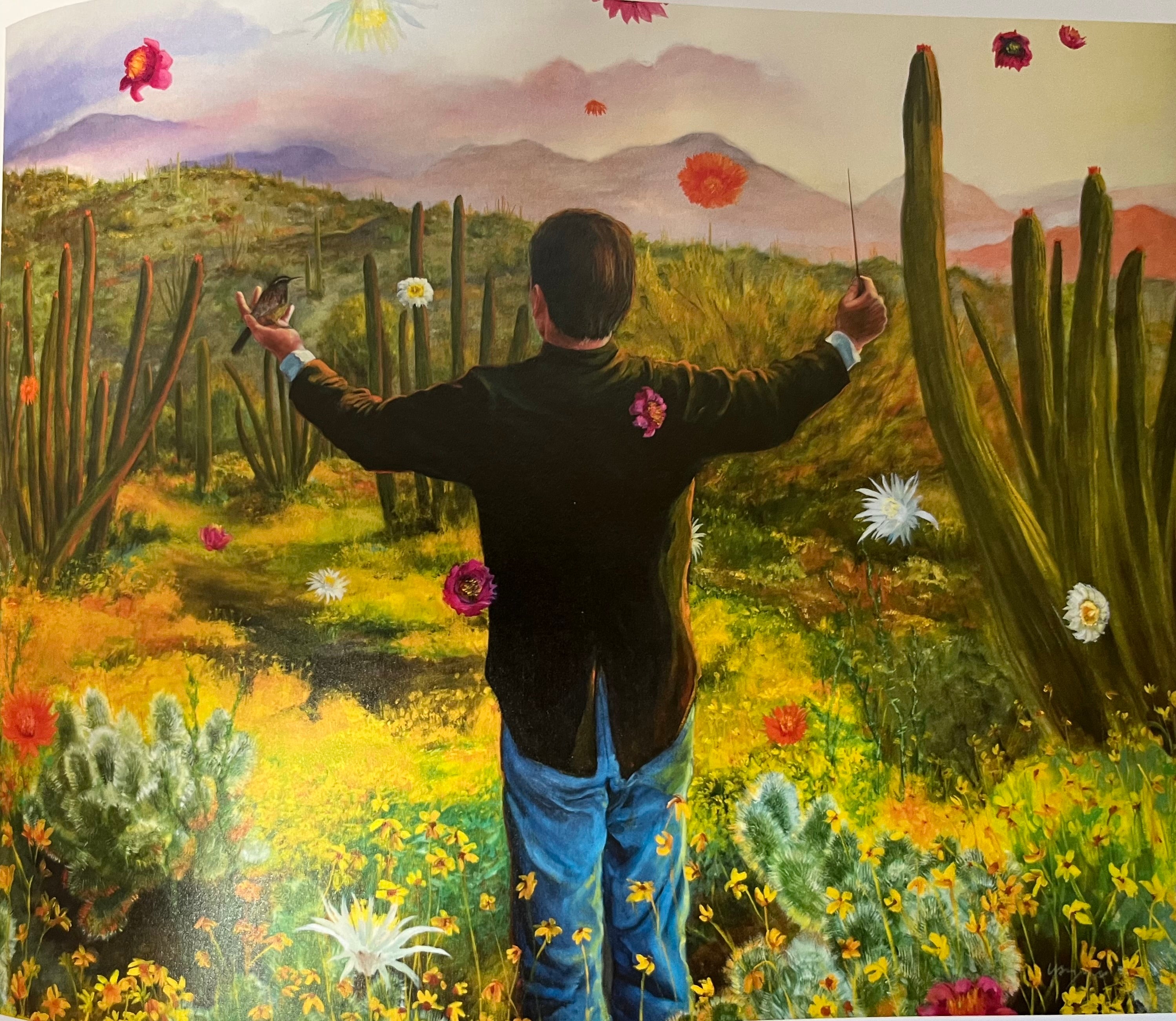

“Orchestrating a Blooming Desert” (2003), by Steven Yazzie.

Yazzie’s painting, “Orchestrating a Blooming Desert” (2003), oil on canvas, is the image used on the National Gallery of Art’s press releases and museum links. But seeing it in person was much more dynamic. Its saturated colors, size, playfulness, and unusual placement of the figure with its back facing viewers drew crowds of viewers. Yazzie is a multidisciplinary artist who says his work “explores the complexities of the post-settler colonial Indigenous experience as it relates to personal identity and community relationships. Our essential connection to the land is the source of life, stories, conflict, and healing.”

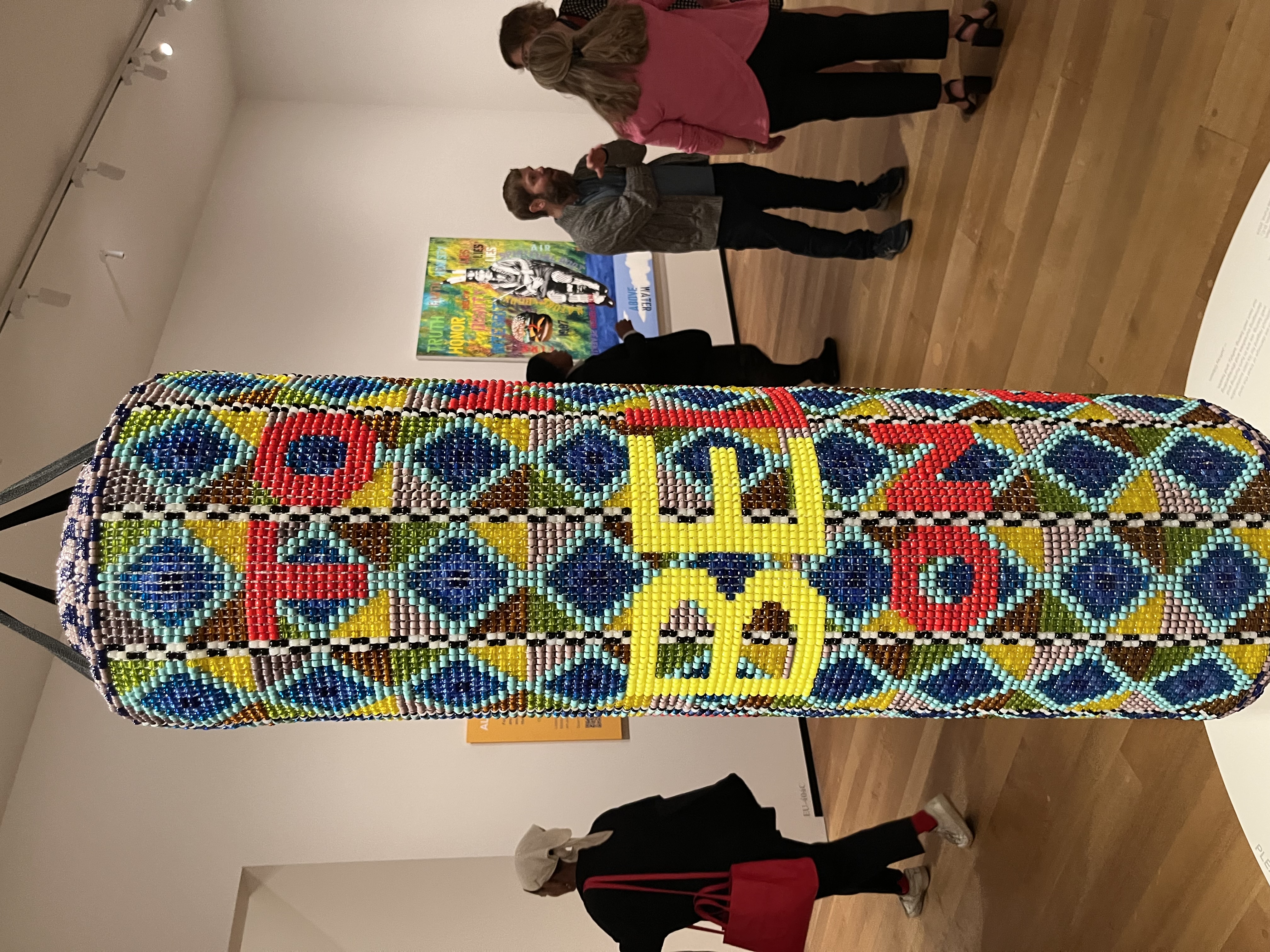

“To Feel Myself Beloved On The Earth”, 2020, by Jeffrey Gibson.

Jeffrey Gibson (Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians/Cherokee Nation) is well known for his participation in the 2019 Whitney Biennial and his recent selection as the first Indigenous artist to represent the United States at the 2024 Venice Biennale. The title of his work, “To Feel Myself Beloved on the Earth” (2020), incorporating the found materials of a punching bag, expanding foam, acrylic foam, plastic and glass beads, and artificial sinew, makes a statement that is cohesive with his artist’s statement about Indigenous kinship philosophies that involve acknowledgement of ancestors, living relatives, “and extensions of our own minds and bodies.” He says, “When we damage or treat the land without regard for its own sustainable well being, we are in turn hurting and damaging ourselves and disregarding our own well being, safety, and health.” Gibson’s use of a punching bag alludes to the balance that is needed to respectfully steward the Earth’s resources while simultaneously caring for the Earth and the gifts it gives us.

I would like to express my gratitude posthumously to Tremblay (1945-2023), who passed before this exhibition opened. She was always kind, supportive, and generous in all her artistic endeavors with me and other Indigenous artists. Her legacy will live on in her inspiring, stunning, and provocative body of visual and literary works. I also want to thank Smith for her vision, advocacy, support, love, scholarship, mentoring, and friendship that she extends to Indigenous cultural artists throughout Turtle Island. So many of us owe much of our success to her continuing encouragement over the years. Aho.

--Phoebe Mills Farris, Ph.D. (Powhatan-Pamunkey) is a Purdue University Professor Emerita, photographer, and freelance art critic.

Top photo: Group shot of some of the exhibit's participating artists and curators.

All photos by Phoebe Farris.