Written by Madeline McGill

Photos by Vera Narvaez-Lanuza

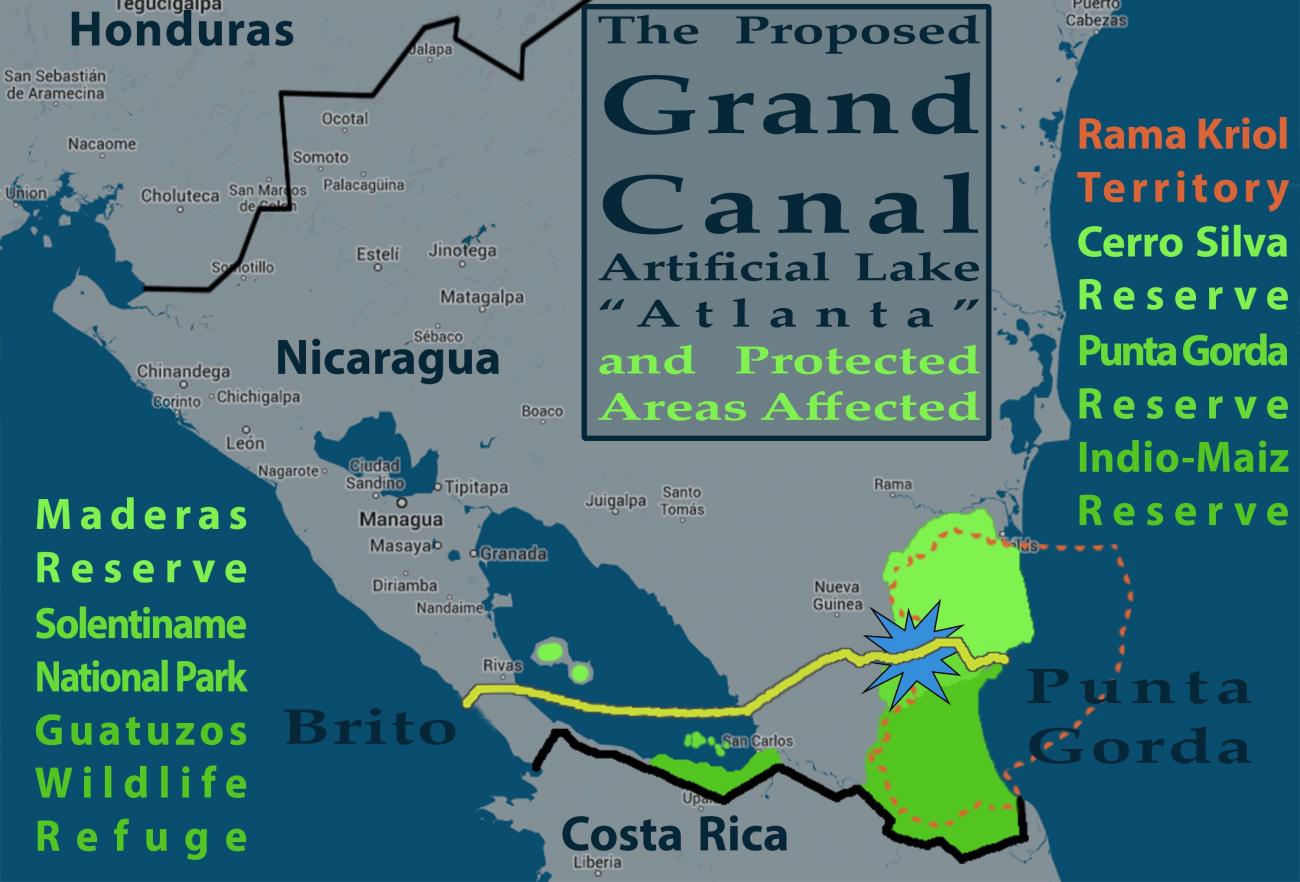

Many remember the controversy of the Panama Canal, a 77.1 kilometer canal that cuts through the Isthmus of Panama. The project was marred by decades of debate, thousands of worker deaths, a US-backed coup d’etat, and years of violent riots from Panamanians before it reached completion. Now, a similar project stands to exceed the scope of the Panama Canal in both size and depth. In June 2013, Nicaraguan officials approved a $50 billion (US) deal with a Hong Kong firm to oversee the construction of a 278-kilometer long canal. The HK Nicaragua Canal Development Investment Company’s proposed project would attempt to link the Pacific to the Caribbean, allowing the passage of container ships too large for passage through the Panama Canal.

The construction of the canal promises environmental abuses and human rights violations as the proposed route cuts through the land of multiple Indigenous territories on Nicaragua’s coasts and within its mainland. Thousands of people are expected to be impacted with many being forcibly displaced, primarily including the Kriol and Indigenous Rama people, in a clear violation of Indigenous autonomy laws in Nicaragua and international human rights documents. The area in question for Indigenous communities is no small range; 52 percent of the proposed route passes through traditional lands belonging to the Indigenous Rama and the nearby Kriol community. The lands that make up the majority of the canal’s route are deeply intertwined in the livelihoods of Indigenous peoples of the region, including precious forests, biodiversity, and water systems. Many fear that the construction of the HKND canal will severely affect the communities’ ways of life.

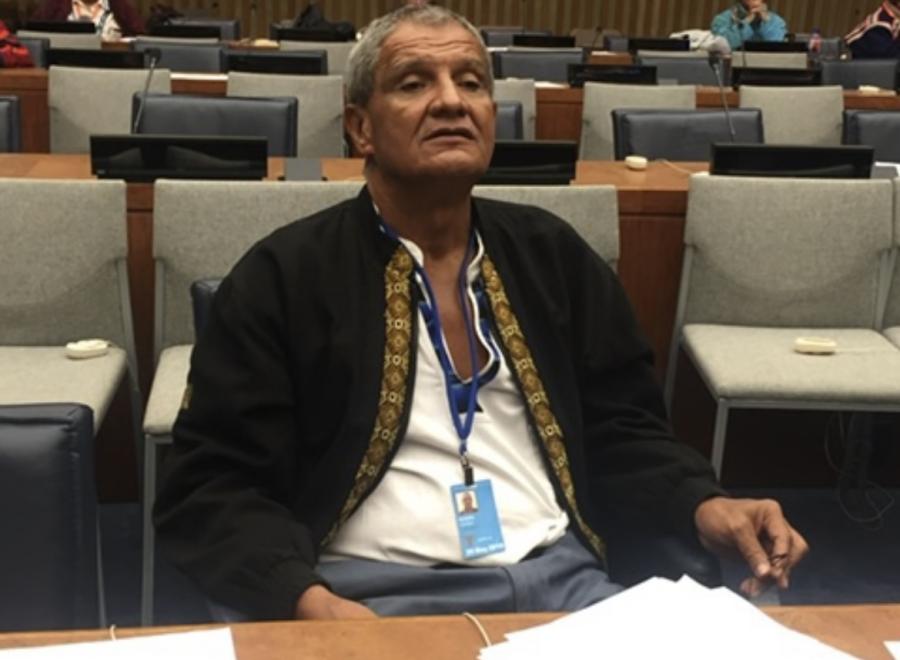

The Nicaraguan Government has failed to properly consult Indigenous communities regarding the canal’s construction. Rama-Kriol officials have demanded that their right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent be respected, but the government has failed to engage leaders at every stage of the process. Many Indigenous community members fear that their options are limited. “We are fighting a big monster,” said Carlos Wilson Bills, president of the Bangkukuk, in the Kriol English spoken along the Miskito Nicaraguan coast. “I feel like that big monster cannot just come and take us out of here. We have the last word about this issue of the canal, because if we say we want it, they could come. But if we say we don't want it, it cannot come, because the land belongs to the Indian people. And we have the last word,” he said in a documentary produced by the Center for Assistance to Indigenous Peoples, or CALPI by its Spanish acronym.

The Nicaraguan Constitution of 1987 recognizes the Indigenous cultures that reside on the land and their right to maintain their languages and cultures. Two additional laws, 28 and 445, grant autonomy and “the use, administration and management of traditional lands and their natural resources” to Indigenous people. Additionally, Nicaragua signed on to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People in 2008 and ratified ILO Convention 169 in 2010, a legally binding document guaranteeing prior consultation before such projects. By failing to consult their Indigenous population, the government has repeatedly failed to respect their rights to autonomy and Free, Prior and Informed Consent. In June 2013 Canal Law 840 was passed, amending this legislation to further the government’s interests by accommodating the construction of the canal and giving the development firm the right to expropriate land and natural resources.

“Those who suddenly find themselves landless will be reimbursed for their ancestral lands based on the assessment of the land’s value for tax purposes, as of June 2013,” stated Axel Meyer, president of the Nicaraguan Academy of Sciences, in an interview with National Geographic. “These individuals can register a complaint about the amount of compensation being offered to them, but they cannot register complaints about the land being taken from them.”

For many Indigenous Peoples, this law might as well be a death sentence for traditional cultures, languages, and lands. In an address to the Washington, D.C.-based Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Rama leader and lawyer Becky McCray further conveyed the damage the canal would have to the culture of the region’s Indigenous, whose livelihoods and ways of life are deeply entwined with their lands: “If this project gets implemented, there is a strong possibility that the Rama language spoken in Bankukuk Taik will disappear as the last people who speak that language get forcibly displaced from their land.” A language only spoken by several dozen, many fear the multi-billion dollar project will drive the fragile language into permanent extinction with the displacement of its few remaining native speakers.

The government is reportedly anticipating that 7,000 homes may be expropriated to make way for the 278-kilometer canal. However, an independent report by the Centro Humboldt states that the impact will be much greater. The report found that 282 settlements and 24,100 homes were identified within the direct area of influence, estimating that the number of people anticipated to be directly affected by construction at over 119,000. The canal’s construction will not only bring the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people, but also irreversible environmental damage. The loss of Indigenous communities will be accompanied by the loss of some of Nicaragua’s most precious and rich resources: its ecologically diverse lands and waters. Included in the project’s concession are the rights to build an interoceanic canal, industrial centers, airports, a rail system, and oil pipelines, and most concerning, the right to expropriate land and natural resources found along the canal route.

Lake Nicaragua, which the proposed route crosses, is the largest drinking water reservoir in the region. Meyer warns that the canal could destroy 4,000 square kilometers of rainforest and wetlands, including hundreds of thousands of acres of forests, reserves, wetlands, and regions Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean coast rely on for sustenance and farming. “The effects of construction, major roadways, a coast-to-coast railway system and oil pipeline, neighboring industrial free-trade zones, and two international airports will transform wetlands into dry zones...remove hardwood forests, and destroy the habitats of animals including those of the coastal, air, land, and freshwater zones,” he said in his interview with National Geographic.

Environmentalists and local communities fear that should they be able to keep their traditional lands, environmental damage will be so severe that the region will no longer be able to sustain traditional livelihoods. “It will destroy we,” said Edwin McCream, an Bangkukuk community member, in an interview with Al Jazeera America. “When I mean it destroy we, we’re not going to get turtle, we’re not going to get fish, we’re not going to get lobster, we’re not going to get shrimp, and from the bush we’re not gonna got deer, we’re not gonna got gibnut, we not have no kind of animal if the canal come.

The Nicaraguan government has not been upfront regarding anticipated environmental damage from the canal. With environmental impact assessments still underway, construction on access roads has begun in anticipation of the assessment’s completion. Meanwhile, the social impact assessment conducted by the Nicaraguan government, if being conducted at all, has lacked any transparency. While quick to boast the economic impact of the canal, officials have blatantly disregarded the needs and fears of community members from coast to coast. A coalition of 11 groups including affected Indigenous communities and environmental and legal organizations submitted a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights criticizing the rights violations inherent in the Canal Law. In a hearing on March 16, 2015, McCray declared to the Commission, “The state’s omission of material in consultation with Indigenous Peoples and Afro-descendents denies our relationship to our lands and our social structures, flagrantly violating our territorial rights, our right to participation, and our right to self-determination.”