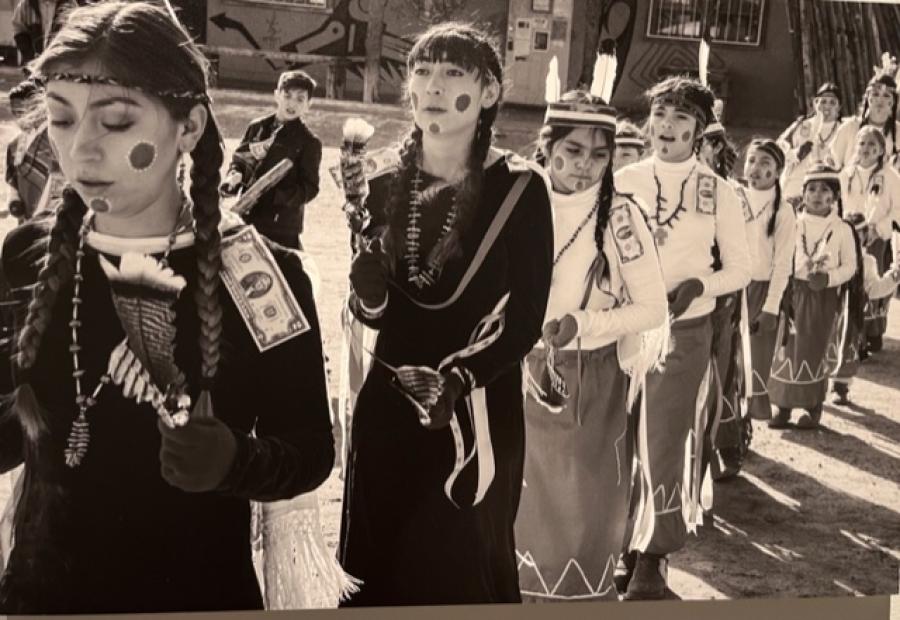

Cultural resilience has been used by Native Americans for centuries as a means to survive, using oral traditions, spirituality, family strengths, elders, tribal identity, ceremonial rituals and the need to give back to one’s tribe and family as tools to help them live and function in a majority society.

The following two Cherokee stories, an ancient traditional story and a modern autobiography, are examples of this idea. At the heart of the stories is tobacco, a powerful, sacred symbol of the Cherokee culture, and through these stories we can see how, through oral traditions, cultural resilience has evolved into the holistic survival of Native Americans.

How They Brought Back the Tobacco: A Traditional Cherokee Story

In the beginning of the world, when people and animals were all the same, there was only one tobacco plant, to which they all came for their tobacco, until the Dagulku geese stole it and carried it far away to the south. The people were suffering without the plant, and there was an old woman who grew so thin and weak that everybody said she would soon die unless she could get tobacco to keep her alive.

Different animals offered to go for the tobacco, one after another, the larger ones first and then the smaller ones, but the Dagulku saw and killed each one before he could get to the plant. After the others, the little Mole tried to reach it by going under the ground, but the Dagulku saw his track and killed him as he came out.

At last the Hummingbird offered, but the others said he was entirely too small and might as well stay home. He begged them to let him try, so they showed him a plant in a field and told him to let them see how he would go about it. The next moment he was gone and they saw him sitting on the plant, and then in a moment he was back again, but no one had seen him going or coming, because he was so swift. “This is the way I’ll do it,” said the Hummingbird, so they let him try.

He flew off to the east, and when he came in sight of the tobacco, the Dagulku were watching all about it, but they could not see him because he was so small and flew so swiftly. He darted down on the plant—tsa!—and snatched off the top with the leaves and seeds, and was off again before the Dagulku knew what had happened. Before he got home with the tobacco, the old woman fainted and they thought she was dead, but he blew the smoke into her nostrils, and with a cry of “Tsalu! [Tobacco]!” she opened her eyes and was alive again.

It is not surprising then that very early documentation revealed the importance of tobacco as a main staple used by many tribes, described by Christopher Columbus in 1492 as a sacred plant to the Indians with a “life affirming, positive spiritual role, a food of the spirits.” Even in a more contemporary Cherokee account, tobacco was noted to carry the smoke’s message to the spirits in the sky as a means to provide protection, to bring luck or to keep things calm, or, in a more sinister approach, to conjure another person. Tobacco was truly seen by the Cherokee as a powerful medicine of many virtues and held at its center the very essence of being Cherokee.

Tobacco: An Autobiographical Version of the Story

When I was growing up, there were certain cultural factors instilled in my siblings and me by our paternal grandparents about what being Cherokee meant. If I could choose only one poignant example in my memory, it would be that of being “doctored” by our grandpa. This usually involved our having a physical illness of some kind. We would tell our parents that we were sick, then we would load into our family vehicle, which was usually an old pickup truck, and travel three miles of dusty Oklahoma dirt roads to Grandpa and Granny’s house.

After the preliminary visiting would take place, with my grandparents speaking Cherokee to my dad and him responding in English, Daddy would report to Grandpa what was going on with us by describing our symptoms. For me, it usually involved headaches, especially during the summertime. After awhile, Grandpa would rise from his chair and go to the kitchen, where a variety of leaves, roots, herbs, teas, and salves, could be found in various pots and pans on the back of Granny’s old wood cook stove. If the medicine was not readily available in the kitchen, Grandpa would retreat to the woods near his house to retrieve what was needed among the native plants. I must say that I never knew Grandpa to actually grow his own tobacco for ceremonial use, unless the cultivation was covert. I always assumed that the tobacco was purchased from the store in town where he and Granny “traded.”

When the gathering and preparation process was done, Grandpa would go out and beckon his ailing grandchild to join him alone in the bedroom that he shared with Granny. He would then motion for us to be seated in a straight-backed chair that he had brought in from the kitchen for this purpose. He would then stand in front of us, our faces squared with his. The atmosphere and the mood in the room would be very solemn and reverent. Although I can no longer recall the steps or methods in the order they came, a cup of water was always involved, along with prayers and chants in the Cherokee language. As he prayed, Grandpa would sometimes lay his hands on our head, stomach, or whatever part of our bodies was giving us trouble. The doctoring ceremony usually lasted for a few minutes, but it seemed to always climax with Grandpa taking a drink of water from the glass, placing tobacco in his mouth and spraying it over us with a fine mist that would cover our head and face. At the conclusion, he would pat us and say in broken English, “You be alright.” Always respectful to our elders, we would thank him and then run off to play, believing that we would be alright—and we were.

Tobacco was also used by my uncle, who would place it in his pipe each evening before bed and blow the smoke on his children, and on me whenever I would stay the night at his house. After this act was completed, he would take his pipe and walk around the outside perimeter of the house, blowing tobacco smoke out as he went along. When I asked him why he did this, he would only say that this was used for protection and to keep things from “bothering” us in the night.

When going to the public school the next day after being doctored by my Grandpa or smoked by my uncle, I was always aware that these were things that I could not share with my schoolmates or teachers. I must confess that not sharing these healing ceremonies and rituals with my friends was partly based upon shame, because I feared that my classmates would think of my family as being primitive. The other part of my not telling was an innate understanding that they were different than we were, and they would not understand. You see, Cherokees were not exempt from derogatory stereotypes in the early 1970s, even when we lived in the capital of Oklahoma’s Cherokee Nation. This assumption was validated when, in the third grade, I stayed the night at a white friend’s house. The friend later told me that her mother had explained to her that I would not be using forks or spoons at dinner, because Indians only ate with their fingers. Maybe her mother’s assumption was partially reasonable, because I am certain that these white folks’ Grandpa did not spit on them when they were sick!

Looking back, I think about how separate these two worlds were: the essence of being Cherokee by the practice of Cherokee traditional medicine, and the majority society as was introduced to me by the public educational system. However, even as a child, these paths intermingled, because I walked in both, and I learned how to navigate both. But just when I would think that I had mastered the walk and found some semblance of balance with it all, a curve ball would be thrown at me, sending me tumbling.

Sometimes the mixed messages even came from my Cherokee family. For example, later on in my adulthood, my dad’s sister laughingly remarked that when her daughter was small she did not like to go and see Grandpa “because he spits on me.” Perhaps Grandpa was aware of this, as in his very old age he lamented to me that none of his six children expressed an interest in learning the traditional medicine practices—and when he died, he said, this knowledge would die with him. Feeling very important as his first born granddaughter, whom he christened with the Cherokee name of his beloved mother, I immediately proclaimed, “I’ll learn, Grandpa; teach me!” Just as quick, his reply was, “You too much a white woman.” Stung, ashamed, and embarrassed, I recoiled and left Grandpa that day, ailing in his nursing home bed, alone in a closed, dark, and bare room.

In retrospect, it is interesting that I did not take my Grandpa’s statement to be biased against my gender, as my Cherokee family never implied to me that I was anything less than a man because I was born a woman. This was demonstrated by the fact that my grandmother was the matriarch of our family, and everyone understood this, especially Grandpa. I also grew up being familiar with Cherokee medicine women, one of whom was a relative of Grandpa’s and made frequent visits to my grandparents’ home. You see, his bias was against the white blood and culture that is also a part of who I am. Later, when working through my own personal offense, I tried to objectify his response by considering the fact that I knew very little of the Cherokee language, a major component of understanding the culture. Besides, was I not in fact acculturated to mainstream society if I was getting a college education? Even though Granny was my strongest supporter in achieving a college degree, she made it clear to me that I was to use my formal education to help the Cherokees. And did I not honor her wishes?

In trying to overcome my personal pain at being denounced by my grandfather as too white, I tried to see the world through his eyes. The losses in his latter life were enormous: his physical mobility was now hindered by a stroke and a leg amputation; he was unable to die in the comfort of his own home surrounded by his blood kin; and he had no one to converse with him in his tribal language on a daily basis. The nursing home staff once tried to remedy this situation when they placed an elderly Native man in the room with him. Later Grandpa grunted with disdain, “He a Chickasaw!” As if this was not enough, then there was his children’s lack of interest in learning the practice of the Cherokee medicine that as a young man he had earnestly acquired from his uncle. He waited to die, receiving comfort only in the knowledge that the purpose of his life was now spent lying in his bed, “praying for my kids and grandkids all day long, that’s all I do.” Even in loss and disappointment, his hope for his future generations continued to be petitioned daily to his Creator, just as his former medicine ceremonies and prayers brought hope that we would be healed, and we believed that we would.

Shortly thereafter Grandpa did die. His life ended as a testimonial to the blending of Cherokee and Anglo cultures that in time became his life. He spoke fluent Cherokee and conversational English; he was literate in the Cherokee language, but was never interested in learning to read in English. In the confines of his home he practiced traditional Cherokee medicine, while he publicly confessed his Christian faith as a Baptist minister. And having married a half-blood Cherokee woman, all of his descendants were mixed with white.

His Christian memorial service was delivered by one of his Cherokee ministerial friends, who described him as a “good deacon.” The service was spoken first in Cherokee and then followed by an English translation for “non-Cherokees,” including all of his grandchildren, who did not understand the language. The funeral songs were all sung in Cherokee, with one telling the story of our dying ancestors’ crying out to the Creator to save their orphaned children on the infamous Trail of Tears, to the final destination later known as the great state of Oklahoma. The songs were wailed out, sad and forlorn, by Cherokee elders, echoing the loss that we all felt in our hearts. I remember looking toward the casket that held my grandpa’s body and thinking that this is the last of the Cherokee full bloods in our family linage. There will never be another one, just as there will never be a person who was able to learn the Cherokee medicine from Grandpa. But we know his story; it is also our story, and will become the story of our future generations only if it is repeated.

Bringing Back the Tobacco

Native American oral traditions involve repetition, with variations usually centering on the theme of life, death, and rebirth. The stories are multicultural and complex, as they are told both from within tribal relations and without tribal perspectives, interpreted through the view of others who do not personally know their subjects, as these take their view from the outside looking in. And finally, the stories are interpreted through Indigenous eyes, based on the shared experiences of the elders and those experiences that are personally owned by the individuals who have lived them. Sometimes there is astonishment at the method in which the stories bring back to life back what being Native means. In the ancient Cherokee traditional story, the tobacco lived and sustained life, as the Cherokee would die if the tobacco was no longer accessible to them. But then the tobacco was retrieved by a most unlikely source: a small, willing hummingbird that possessed the virtue of being brave and swift.

In the modern autobiographical rendition, the tobacco lived in a grandfather’s medicinal practices, through which he demonstrated to his grandchildren what being Cherokee meant. And the tobacco died with the grandfather. But the tobacco was resurrected by a most unlikely source: a willing mixed-blood granddaughter who possessed the virtue of taking to heart what being Cherokee meant. Although unable to speak the Cherokee language and perhaps not enough Indian blood by some accounts, she used her heritage and formal education to revive the importance of tobacco into yet another variation. The ancient story brought hope to the hearts of the people that the tobacco would be retrieved and the Cherokee people would survive. The modern version seeks to do the same.

Healing via tobacco can occur both spiritually and physically, and it is often in a protective covering that is a part of one’s cultural identity, and it is sometimes imparted in stories or in lived examples that later become stories. This is cultural resilience. Through the passage of time, traditional stories can and do change, but their essence remains the same, as they always reflect the cultural resiliency of Native people. And we are Indigenous survivors whose “constitutional vigor” from our warrior ancestors guides us into an ever-evolving adaptation.

Virginia Drywater-Whitekiller is a professor of social work at Northeastern State University, in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. She is married to a fellow Cherokee, and together they have four children. Her writing interest involves cultural resilience theory and all things Cherokee.