When the signing of Treaty 5 took place in Norway House, Manitoba in 1875, the leaders representing the Cree hunters and their families who put their "X" next to their names in the Roman alphabet understood that they were being assured the future prosperity of their people, that they were sharing the land with the settlers only to the extent that it would not interfere with their practices of hunting, fishing, and trapping. Today in Cross Lake, a community of some 5000 Crees in northern Manitoba, the significance of this treaty history is being revisited in the light of broken government promises. Sandy Beardy, an elder in Cross Lake, explained the significance of Treaty 5 by describing an image engraved on treaty metals, an image with such significance to him that he wore it embroidered on his jacket. "[Y]ou see the sun here, and the grass and the river flowing, and a wigwam here, and a small one here, and a wee small one. This treaty will be in existence as long as the sun [shines], as long as the grass grows, as long as the rivers flow…This is what the Indian people understand. So they signed the treaty…They made a deal."

Most of us are familiar with the use of treaties as instruments of land surrender and the frequent failure of governments to honor the promises made to indigenous peopies. The government of Canada, despite a considerable diplomatic investment in the upholding of international human rights, is no exception to the pattern of treaty promises followed up by strategies of extinguishment.

Cross Lake's situation, despite Canada's human rights ambitions, is sadly similar to that of indigenous peoples in many parts of the world, but it is unusual in terms of the broad spectrum of strategies its leadership is using to bring the governments of Canada, Manitoba, and the crown corporation, Manitoba Hydro, towards a respectful approach to honoring their treaty obligations.

The Churchill/Nelson River Hydroelectric Project

In 1966 the governments of Canada and the province of Manitoba entered into an agreement to jointly undertake the development of hydroelectricity on the Nelson River, with water flow to generating stations to be increased by a major diversion of the Churchill River. This was done without consulting the people whose livelihood would be affected and whose treaty rights, which include guarantees of the continued viability of waterways for subsistence and navigation, would be violated. Construction was begun on the Kettle Generating Station in 1970 without an independent environmental review and without hearings to elicit the views of the native people to be displaced. Through the early 1970s other dams were constructed under similar circumstances of environmental destruction, loss of livelihood for native peoples, and infringement of treaty rights.

The Northern Flood Agreement

The circumstances in which a hydroelectric mega-project was forced upon the people of northern Manitoba did not long go unnoticed. In 1975, a Panel of Public Enquiry, spearheaded by an interdenominational coalition of church groups, was convened in Winnipeg and the native community of Nelson House. The testimony at these hearings made it public knowledge that the Nelson River project was damaging a lush and varied but fragile ecology in ways that were little understood due to lack of reliable research. The public heard testimony from Cree fishermen about the Hydro project causing reversal of natural water regimes, with high water in winter, and low water in summer, resulting in the destruction of spawning grounds and loss of a viable fishery. Cree speakers lamented the flooding and erosion of ancestral burial grounds. They spoke of the dangers of navigation, resulting from weak ice and debris in open water which severely limited their trapping way of life and spiritual attachments to the land. Above all, the inquiry raised the concern that no meaningful efforts were being made to compensate native peoples or to reconsider development plans to minimize their environmental and social impacts.

Under pressure from such revelations, the governments of Canada and Manitoba and Manitoba Hydro negotiated an Agreement with five of the native communities that had already suffered from existing hydro development: Split Lake, Nelson House, York Landing, Norway House, and Cross Lake. The Northern Flood Agreement of 1977, in comparison with Canada's other modern day treaties such as the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and the yet to be ratified Nisgaa Agreement, is generous and imprecise. Yet Warren Allmand, Canada's Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development at the time the NFA was signed, explained that its imprecision is no different from international treaties which leave some of the mechanisms of implementation to be worked out after the signing.

What is clear is that this modern day treaty is ambitious in it goals of alleviating the destruction of the Cree peoples' subsistence and improving their communities. The NFA promises compensation for injury or of loss of life on the waterways made hazardous by debris or unstable ice. It promises remedial measures to remove debris, secure eroding shorelines, and restore burial sites. It promises land exchange, with four acres of new reservation land to replace every acre of reserve land that was flooded. Perhaps its most ambitious goal is contained in Schedule "E" which calls for the "eradication of mass poverty and mass unemployment," the alleviation of conditions in which roughly 85 percent of the Cree population was (and continues to be) dependent upon welfare, with little hope of finding even seasonal employment. Manfred Rehbok, one of the lawyers who drafted the NFA, was inspired by the Marshall Plan, having lived through the rebuilding of post-World War II Germany, and some of the ideals and choices of wording contained in Schedule `E' of the NFA arose from his perception that the Cree communities affected by the Nelson River mega-project faced a comparable, though smallerscale, challenge of development to that of post-war Europe.

Non-Implementation and Extinguishment

In the decade that followed the signing of the Northern Flood Agreement, the governments of Canada and Manitoba and Manitoba Hydro did not set aside funds for meeting NFA obligations, but engaged in litigation, providing minimal compensation only for damages directly attributable to the hydroelectric project. They focused their attention on small claims, forcing them into arbitration and courts, while ignoring the most important provision of the NFA. No land has been exchanged for Cross Lake, even though the NFA calls for a six month deadline upon ratification. The community is still hugely welfare dependent, with a housing shortage, based on government criteria, of more than 500 units. Although the government of Canada has primary responsibility for native peoples, it did not honor its own NFA obligations, and, in an action prohibited by Article 2.4 of the NFA, cut regular program funding to the five signatory communities in half in a mistaken anticipation of the NFA benefits "kicking in."

In 1985, Manitoba Hydro made the first attempt to extinguish the NFA, offering the five bands $30 million to settle, in perpetuity, all resource related claims resulting from the hydro project. Global settlements were also attempted by Canada in 1988 and 1990. Shortly after "global settlement" negotiations failed, the government of Canada cut off funding to the Northern Flood Committee, the organization representing the native signatories of the NFA, resulting in its termination. Then in 1992, despite the fact that the NFA was to last "for the lifetime of the Project," the government of Canada went to each community individually to extinguish the ongoing relationships established in the NFA, except for government liabilities for injuries and deaths caused directly by the project. This was accomplished through so-called "Implementation Agreements," in effect "termination" agreements which put an end to government obligations and overall severely diminish the benefits and compensation due to the native signatories of the NFA. The extinguishment process began with one of the smallest of the NFA signatories, Split Lake, signing an agreement in 1992, and proceeded with York Factory in 1995, Nelson House in 1996, and Norway House in 1997. Local systems of consensus-oriented decision making were compromised through a ratification process based upon referendums in which financial inducements (referred to euphemistically as "percapita distributions") of $1000 were offered to each individual, immediately payable upon acceptance of the "Implementation Agreements." In Norway House, despite the fact that many residents are functionally literate only in Cree syllabic writing, the referendum ballots were exclusively in English.

Cross Lake's Refusal

In October 1997 Cross Lake was offered a "Comprehensive Implementation Agreement," presented to the community as a new instrument for the provision of its NFA entitlements. The CIA offered a guaranteed pool of money, contributed by Canada, Manitoba, and Manitoba Hydro, which amounted to approximately $6 million per year for 24 years. At the end of 24 years, Cross Lake was to be left with a $60 million Hydro bond to be reinvested for future annual income. It also provided land exchange with the ratio of 16 acres for every acre affected, on the surface a much more generous provision than the requirement of 4 acres in the NFA. Although there was widespread initial support for the CIA, close scrutiny of the document raised some concerns that could not be addressed to many people's satisfaction. A consultation process in which the CIA was discussed in fifteen informal "Circle Groups" in the community was instrumental in raising concerns about the CIA. One important question, expressed most strongly by the Council of Elders, focused on the lack of self-government principles in the CIA, especially in its regime of land management, which gives the province of Manitoba jurisdiction in resource development on reserve lands. A second important concern was that all claims, with the exception of personal injury and deaths attributed directly to the Hydro project, would no longer be the responsibility of Canada, Manitoba, and Manitoba Hydro, but would be in the hands of a Cross Lake claims officer, with compensation moneys to be paid for out of the $6 million annual fund. This left questions about the lack of honor involved in essentially appealing to one's own community to redress wrongs done by governments and created doubts that enough money would be left over to fulfill the important provisions of community development and employment programs contained in the NFA. As Sandy Beardy explained to me, "Supposing if I said, build a $100,000 home, and I only give you $50,000. Can you build that house?" Above all, doubts were raised by the legal language of the document which encouraged the reasonable suspicion that terms such as "releases" and "indemnities" were a way for the government signatories to back out of their obligations, to in fact "terminate" or "buy out" the NFA. Elder Gideon McKay expressed the view that only by sticking to original long-term commitments of the NFA can the governments' promises be fulfilled: "The promises that were made in the Northern Flood Agreement were supposed to stand for as long as the hydro project is in existence…This is why we don't want to do away with our Northern Flood Agreement. We don't want the [governments of Canada, Manitoba and Manitoba Hydro] to break away from the promises that they made."

When the CIA negotiations failed in 1997, a reawakening began in Cross Lake, a confused reawakening in which anger and sorrow over years of unatoned grievance mingled uncomfortably with a sense of empowerment. A dramatic shift took place in Cross Lake's NFA implementation strategy from renegotiation to rebellion. In March 1998 a protest was staged at a ferry crossing seven miles outside of Cross Lake which blocked Manitoba Hydro vehicles, including a fleet of semi-trailers carrying expensive heavy equipment, from entry onto reserve lands. (Hydro representatives can now enter Cross Lake only after completing a "permission to enter" form that is reviewed at the Band Office and forwarded to Cross Lake's Band Constable.) Speaking tours took place in Minneapolis and Winnipeg in the hope of making the buyers of Manitoba's power aware of the human rights and environmental violations associated with the energy they use daily. Most recently (as I write) Cross Lake's Chief, Roland Robinson, has traveled to Geneva, on a trip funded by the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, to bring his concerns to the United Nations Human Rights Commission.

In addition to these familiar forms of resistance, Cross Lake has developed a law making strategy with important implications for indigenous self-determination and self-government. On October 30, 1998, the Pimicikamak Cree Nation of Cross Lake passed its own Hydro Payment Law which, in effect, provides the residents of Cross Lake and other Manitoba Hydro customers with the option of paying their Hydro bills into a Trust, to be administered through one of Canada's largest banks, the Royal Trust. The idea for this law stemmed from the contradiction, obvious to many, of Cross Lake being owed so much by Manitoba Hydro (because the NFA involves ongoing commitments a precise dollar amount cannot attached to Hydro's NFA obligations) while the households and institutions of Cross Lake have paid at least $2 million per year in electricity bills. The Hydro Payment Law, in its simplest terms, is a form of "debtors possession." The law making authority upon which it is based is not Canada's Indian Act, nor a form of self-government negotiated through the state, but a renewal of that authority which preceded Canada's confederacy and which had never been surrendered, referred to in Cross Lake, in a sophisticated borrowing of legal language, as "inherent jurisdiction." Under this renewed inherent authority, Cross Lake established a legislative assembly called the Four Councils, an Elder's Council, Women's Council, Youth Council, and, in an important inclusion of state authority, the Chief and Council. The law was proposed in 1996, drafted in consultation with lawyers, reviewed, discussed, and amended in each of the Four Councils, then further discussed and voted on by the community members (with a result of 59 in favor, none against, and two abstentions) in an open meeting before being ready for ratification on October 30, 1998. The day of ratification was celebrated in Cross Lake as Pimicikamak Cree Nation's Independence Day, in recognition, not of a severing of ties with Canada, but of the powers that had been put to use, powers which add important practical meaning to the term "self-determination."

On Cross Lake's Hydro Payment Day a law had been passed in a native community, under inherent jurisdiction, which punishes a crown corporation and embarrasses two levels of government, with the open participation of a major financial institution. The consequences of this have only just begun to unfold.

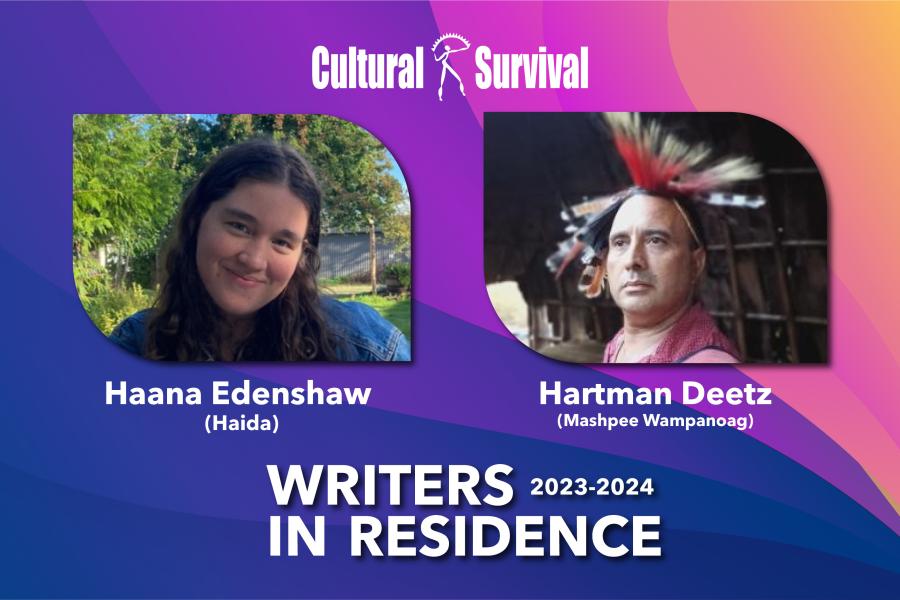

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.