During our first week at the Philippine Refugee Processing Center (PRPC) we walked to one of the camp's markets early every morning and had waved to a young adolescent Amerasian (age 14) on the way. On the third morning, instead of simply waving she raised her hand quite high and yelled out, "I'm American, I'm American too." Her exclamation, along with the often-posed first question to us: "Are you American?" has the rejoinder, "So am I." It is not a statement of identity but it is one of identification. It serves as a form of introduction that grants the understood desire to explore the range of expectations, hopes, fears and fantasies associated with the excitement (and ambivalence) about "going to America."

Background

Since 1982, some 3,750 Vietnamese Amerasians and nearly 5,00 accompanying family members have arrived in the United States through the Orderly Departure Program. Estimates of the numbers of Vietnamese Amerasians still in Vietnam vary widely, though most informed sources now agree at 12,000-15,000. There are currently almost 9,000 official cases on file in Bangkok, 79 of whom have already been legitimized as American citizens. Although the Vietnamese government ceased issuing new exit visas in January 1986, there has been genuine progress over this political deadlock and it is expected that the numbers of Vietnamese Amerasians coming to the US will soon increase significantly.

Many references to Amerasians have described them as children. However, given the gradual withdrawal of Americans (both military and civilian) from Vietnam in the early 1970s and the exit of almost all Americans with the fall of Saigon in April 1975, even the youngest Amerasians are now over 10. Thus, the vast majority are adolescents. At 18 they have reached draft age in Vietnam and those who come to the US do so as young adults, arriving without accompanying relatives.

Misperceptions

Increasing attention has been given to the so-called "Amerasian issue"; in particular, to those Amerasians born of American fathers and Vietnamese mothers during the Vietnam War. Unfortunately, most reports in the popular press and professional journals alike have been laden with misperception. We believe that, in this case, many people have begun to equate the phenomenon of simple identification with a more mature, established sense of identity. Thus, various well-meaning adults are forcing the issue of identity on Amerasian adolescents and inadvertently are increasing the risk of some premature closure in this process. Most typically, Amerasians area asked, "Are you more American or are you more Vietnamese?"

The observations offered in this article have been generated from our continuing work at the Philippine Refugee Processing Center in Morong, Bataan, from visits to Suan Plu (the ODP "transit center" in Bangkok) and from numerous site visits made to local resettlement agencies across the United States. For the sake of convenience, our use of the term "Amerasian" will refer exclusively to Vietnamese Amerasian and observations should not be generalized to other Amerasian groups. Our purpose is to illustrate the difference between identification and the more integrated sense of self we associate with the term "identity."

While important commonalties do exist for Amerasian youth (e.g., the significant loss of a parent and being biracial), there is also great diversity among them. Their individual histories and environmental experiences range from extreme poverty, with little schooling and hard-felt discrimination, to deep, warm relationships at home, genuine success in the traditional school setting and strong ties to peers and adults alike.

Identification and Identity

Erik Erikson's work on the concept of identity as a stage in the human life cycle is now a universally recognized principle in western psychology. Some attention has been given to children of transcultural or transcracial adoption, yet comparatively little has been written about identity formation in biracial or bicultural children. At this point we know very little about the process of identity formation in biracial/bicultural Amerasian children.

This specific lack of knowledge and insight regarding Amerasian self-concept was demonstrated in the presumption that unaccompanied black or "AfroAmerasians" would naturally and readily identify with black culture in the US. On this premise, most were initially placed with black families. The reactions to these placements, however, varied radically. While a few worked out smoothly and thus far have proven to be good matches, a number of other placement broke down immediately. In some instances, the Amerasian overtly rejected the placement on the basis that the family was black. Without having explored the various perceptions of darker-skinned peoples in Vietnamese culture or the nature of these particular adolescents' prejudices, the assumptions made about their internalized identifications were inaccurate.

We heard Amerasians being openly asked to clarify their sense of identity, as if they had already established a solid sense of self and some dichotomous choice (American or Vietnamese) was warranted. It is of note that one would not expect such integration in American youth of the same age. None of the Amerasians we have come to know suggest he or she has already achieved a state of identity that reflects a genuine sense of who they are or might become. It will take more time for them to integrate past with present experience, develop a balanced perceived of how they see themselves in contrast to how they are perceived by adults and the wider community, and finally, achieve an accurate vision of where they are headed. Such an outcome is, developmentally speaking, an ideal, not always attained even by teenagers and young adults in less complicated circumstances.

In offering this commentary we do not mean to suggest that all of the Amerasians we've worked with are in great inner turmoil. Indeed, many display enormous strength and resiliency. The cautionary observation we are making is that many adults (e.g., reporters, resettlement caseworkers, teachers, foster parents and clinicians) are misinterpreting early, natural statements of simple identification (i.e., "I am like") with genuine expressions of self (i.e., "I am"). Moreover, some adults are unconsciously, out of their own anxiety rooted in their strong attachment to the adolescent, forcing the issue prematurely. Instead of meeting questions or statements by the teenager as they arise, there appears to be a tendency to probe and overinterpret.

Some expressions of ethnic or cultural identification can be quite context-specific. For example, during a visit to a summer camp for refugee youth in the States, we had been talking to a group of adolescents (Khmer, Vietnamese and Amerasians) about how things were going for them in the US and what advice they would have for the adolescents in the PRPC. Many had been in the States for over three years and the discussion centered around typical adolescent concerns, from music and clothes to part-time jobs and obtaining a driver's license and the struggle over paying for insurance. When it became time for the afternoon soccer game, they rapidly divided into Khmer and Vietnamese teams. With no need for discussion by anyone, it was clear that the Amerasians identified themselves as Vietnamese and were as active and central to the team's success as any other players. There was no evidence of any struggle with their sense of ethnic heritage at that moment, yet much of the discussion during the ensuing days dealt with conflicts over their identifications with Vietnamese and American roles and values.

During a visit to a resettlement program's celebration of the Vietnamese Mid-Autumn Festival we met two older Amerasians (17 and 18) who stood out because of their dress and behavior. Somewhat apart from the larger group, the were wearing jackets, buttons and hats that identified them with two major American rock groups. One caseworker had expressed some concern that these young men had seized the popular American music culture and seemed to be rejecting outright their connections to more traditional Vietnamese culture.

However, something quite different emerged as we came to know them. Attendance at the festival was not mandatory. They had come of their own choice. It also became clear that their infatuation with these particular groups (not atypical for adolescents) went beyond clothing and hair style but included genuine interest in and identification with the lyrics of specific songs. In addition, they offered some of the most poignant observations and suggestions when describing how they were doing, what they might do when they finished their respective high school and vocational programs, and what advice they had for other teenage refugees who had yet to arrive in the US. In a sense, this seizing of values of the new culture, be it clothes, music or food, is not to be unexpected nor should it be regarded as any final rejection of their heritage. Such intense identification is often a part of the natural process of identity formation. One suspects that upon integration, salient aspects of their ethnic heritage will reemerge.

Conclusion

Those of us who are involved in their resettlement must not lose sight of the fact that the process of identity formation is exactly that, a process. Given that the majority of Amerasians are adolescents in a period of enormous cultural transition, who must also come to terms with the issues of parental loss and biracial heritage, this process requires and deserves time. We must not unwittingly mistake their initial statements of identification for mature expressions of identity choice nor can Amerasians afford for us to let our own anxieties about their well-being force this issue through the intrusion of probing questions or premature interpretations.

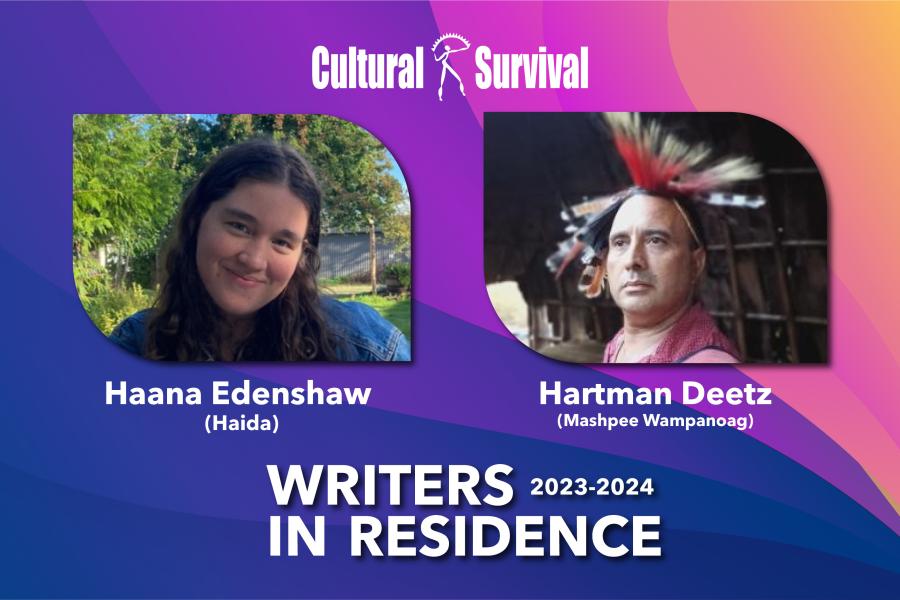

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.