In 1874, a band in Southern Saskatchewan living on the margins of Canadian society signed Treaty No. 4 with the Canadian government and released most of its traditional territory in exchange for a much smaller reserve and promises of farm implements and an annual annuity to ensure its survival. Within 30 years the band’s population decreased nearly 50 percent from starvation and disease and the band was devoid of leadership. In the middle of January, Canada’s harshest month for cold and snow, in the year 1907, Canadian government officials arrived in this community with money and pen in hand, and offered $10,000 if the band agreed to surrender nearly 70 percent of its reserve.

The band first refused. The Canadian officials waited. They asked a second time and on this occasion the band agreed. In a vote of 11 to six, 70 percent of the band’s best arable land was surrendered to the Crown. The Canadian officials were free to open the land to European settlers migrating west. Yet it would be close to 80 years before this Saskatchewan First Nation would formalize a claim disputing the lawfulness of the 1907 surrender and subsequent sale of its reserve land.

The First Nation’s delay can be attributed in part to Canada’s prohibition from 1927 to 1951 of First Nations retaining legal counsel. In 1927 the Indian Act was amended to make it a punishable offense for a lawyer to receive payment from a First Nation to bring a claim against the Crown without the Crown’s consent. When this law was repealed in 1951, First Nations across the country began to mobilize to pursue their claims against the Crown in the Canadian courts. Following the 1973 Supreme Court of Canada decision in Calder v. Attorney General of British Columbia recognizing that Canada’s first peoples have a legal claim to land they occupied before the arrival of European settlers, the floodgates were opened for similar claims to come forward against the Crown from First Nations across the country.

The Canadian government’s response to the plethora of title claims that followed Calder was to create a policy to address what it recognized as its outstanding obligation to the first peoples of Canada. In 1974, the federal Department of Indian Affairs established the Office of Native Claims, a separate entity within the department with responsibility to review First Nation “specific claims”—claims arising from breaches of treaty, breaches of trust and circumstances such as theft of land, and flagrant violations of the fiduciary duties of the Crown. The Office of Native Claims not only had the responsibility to review these claims, but according to the 1982 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs publication Outstanding Business: A Native Claims Policy-Specific Claims, the office should “represent the Minister and the Government of Canada in claims assessment and negotiation with Native groups.” It was immediately clear that this dual role created an inherent conflict of interest and it quickly became an additional grievance of First Nations.

In practice, this dual role translated into the Canadian government not only acting as defendant to a claim, but as a judge to the claim’s legitimacy. The government, then and now, judges a claim based upon legal advice, which it obtains from its own lawyers. The government then renders a decision based on that legal advice, but refuses to share the legal opinion with the claimant First Nation on the basis that the opinion is subject to solicitor/client privilege. This policy operated until 1982, when the federal government admitted the failure of this approach and established a “new” policy.

“To date progress in resolving specific claims has been very limited indeed,” the government acknowledged in Outstanding Business, where it detailed the new policy. “Claimants have felt hampered by inadequate research capabilities and insufficient funding; government lacked a clear, articulate policy.”

Under the new policy, the bases upon which claims could be accepted were more clearly articulated and the Indian Department indicated that it would not allow statutory limitation periods or the doctrine of laches to interfere with the acceptance of otherwise valid claims. But from the perspective of First Nations, the new policy did little to address past grievances. The Department of Justice continued to define “lawful obligations” in a narrow legalistic way, which precluded the acceptance of claims on moral or equitable grounds. The burden upon First Nations to prove their allegations was heavy, especially in light of the evidentiary difficulties associated with proving facts that may have occurred a century in the past. The Department of Indian Affairs continued to refuse to disclose the Department of Justice’s legal opinion rejecting a claim, while insufficient funding prohibited the department from dealing with the deluge of historical grievances and created a growing backlog, along with extraordinary delays in the processing of claims. The First Nations’ greatest objections however, concerned Canada’s inherent conflict of interest in the claims process; a process in which it continued to act as both judge and party.

A First Nation Finds Justice

Canada’s new policy continued to limp along until 1990. Watched by millions around the world, in 1990 the Mohawk community of Kanesatake took up arms against the Canadian military in what was, in its view, an unlawful encroachment upon their traditional territory for a golf course. The Mohawk community sits adjacent to the village of Oka, Quebec, on a scenic point where the Ottawa River meets the St. Lawrence River. The town of Oka had plans to expand a nine-hole golf course to 18 holes. The design called for a fairway to cut into a pine forest the Mohawk declared their sacred ground. The stand-off that ensued throughout the summer of 1990 marked a low point in relations between First Nations and the government of Canada.

In October 1990 the federal government began a new round of reform and sought the input of Aboriginal leaders throughout the country regarding changes to be made to the federal policy dealing with the resolution of land claims. In January 1991, the Minister of Indian Affairs responded by outlining five initiatives for reform. One of these initiatives was the creation of the current Indian Claims Commission. Conceived as an interim measure, the commission was created with power to publicly inquire into and make recommendations concerning claims rejected by the Minister of Indian Affairs. Its decisions, which are not binding on the parties, are required to be made in accordance with the specific claims policy set out in Outstanding Business. In practice, the commission’s inquiry process and final reports provide Canada with the opportunity to reconsider its original position on a claims’ validity.

The Saskatchewan First Nation, who had surrendered its best land in 1907, submitted a claim in March 1989 to the Minister of Indian Affairs alleging breach of treaty, breach of statute, and breach of fiduciary obligations under Outstanding Business. When their claim was rejected by the minister as disclosing no outstanding lawful obligation in 1994, the First Nation requested that the Indian Claims Commission conduct a public inquiry into the reasons for the minister’s rejection. Prior to the creation of the commission in 1991, a First Nation had two options once a claim was rejected by the minister: accept the decision or litigate. The Indian Claims Commission presented a new and alternative third option: a public inquiry.

The commission accepted the Saskatchewan claim on August 31, 1994. Two and a half years later, it recommended the claim be accepted for negotiation on the basis that “the Government of Canada breached [its] fiduciary obligations owed to these aboriginal people.” According to the commission’s 1998 Kahkewistahaw First Nation 1907 Surrender Inquiry Report, “The government not only failed in its obligation to protect the Kahkewistahaw Band but served in fact as a cunning intermediary in procuring a surrender that can only be described as unconscionable and tainted in its concept, passage and implementation.”

The Indian Claims Commission released its final report of this claim in February 1997 and in December of that year the federal government accepted the commission’s recommendation. The then-Minister of Indian Affairs Jane Stewart thanked the commission for its work and detailed report, “all of which have permitted Canada to fully reconsider its position and to accept the Kahkewistahaw claim for negotiation under the Specific Claims Policy.”

In November 2002, the federal government and the Kahkewistahaw First Nation ratified a settlement agreement for $94.6 million. The case of the Kahkewistahaw First Nation serves as a backdrop by which to assess not only Canada’s past policy and process but to also view the government’s current actions. For many, the government’s reconsideration of the Kahkewistahaw First Nation 1907 surrender claim by a public inquiry body underscored the importance of a process devoid of the government’s internal and secret decision making. First Nations could be assured of an independent assessment of a claim’s legitimacy. Ironically, however, while the outcome of this case may be viewed as a success, future claims of similar size and scope will be prohibited from accessing the process that brought this justice.

Reform—Or More of the Same?

The Indian Claims Commission was never intended to be Canada’s final answer to claims resolution but only an interim measure. In 1991 the Canadian government established a joint First Nations/Government Working Group charged with concurrently reviewing the specific claims policy and process and making recommendations for reform to the Minister of Indian Affairs and the Assembly of First Nations, an umbrella organization of the 633 First Nation communities in Canada. The mandate of the Working Group expired in 1993 without the completion of a final report, but draft recommendations prepared by a neutral party were presented in June 1993 noting that consensus was achieved on a single issue: the necessity for an independent claims process.

In the spring of 1997, another joint First Nations/Canada Task Force was formed to consider and make recommendations regarding the structure and mandate of an independent claims body and to make recommendations regarding policy reform. It appeared that Canada was committed to the establishment of such a body, but the recommendations of the Task Force outlining the structure and mandate of a permanent independent tribunal—which were presented to the Minister of Indian Affairs in November of 2001 and subsequently considered by Cabinet—were not accepted by the federal government. Instead, on June 13, 2002, the Minister of Indians Affairs introduced legislation proposing the creation of an independent claims commission and tribunal to resolve and adjudicate specific claims. The legislation would establish the Canadian Centre for the Independent Resolution of First Nations Specific Claims and would have a commission division and a tribunal division, each with distinct functions: the commission to facilitate negotiations and the tribunal to resolve disputes. In the government’s view, stated in a Department of Indian and Northern Affairs news release, “The Commission would enable the resolution of all claims regardless of value, drawing upon the entire range of dispute resolution mechanisms to assist the parties to a specific claim in reaching a final settlement. In contrast, the adjudicative tribunal would be available to First Nations, as a last recourse, to make final binding decisions on the validity of specific claims that have been rejected by Canada and cash compensation on valid claims up to a maximum of $7 million.”

The introduction of this legislation and its subsequent review through Canada’s parliamentary process stirred a backlash from First Nations. The groundswell of criticism focused on three key elements of the legislation: the introduction of a financial cap on claims that could be considered by the tribunal, which would preclude future cases on the scale of the Kahkewistahaw First Nation; the stipulation that, based on the government’s own legal advice, the Minister of Indian Affairs would continue to determine a claim’s validity; and the condition that the appointment of all commissioners and tribunalists would be made by the federal government, calling into question, in the First Nations’ view, the independence of the process.

In the fall of 2002 and into 2003, the Canadian Parliament heard from First Nations coast to coast on why this legislation was not seen as progress and, for some, was seen as a regressive step. Chief Roberta Jamieson of the Six Nations of the Grand River in Southern Ontario appeared as a witness before the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples on May 28, 2003 to flatly reject the legislation. “In Six Nations’ experience the federal government is trying to paddle our canoe and steer Canada’s boat at the same time; by deciding for us, how, where and when our outstanding lawful obligations will be resolved or addressed, if at all,” she testified. “The result is an emerging mountain of unresolved liability that will stand in the way of improved and co-operative relations between First Nations and society as a whole. It is hard to comprehend that the federal government really is acting in the best interests of mainstream Canadians when delaying and avoiding access to a fair and equitable specific claims process.”

Chief Jamieson’s sentiment was echoed by every First Nation witness who appeared before the Senate Standing Committee and yet, on November 7, 2003, the Specific Claims Resolution Act received Royal Assent. Now law, the federal government’s current task is to implement the mechanisms of a commission and tribunal charged with addressing some of the longest outstanding land issues in Canada’s history.

The skepticism with which First Nations may approach Canada’s newest claims body is understandable. Largely ignored by Parliament, they will need to decide whether the Centre for the Independent Resolution of First Nations Specific Claims is a true alternative from the past approach. In practice, they will be asked to waive the value of their claim in excess of $7 million in advance of requesting the tribunal for an independent decision on a claim’s validity. They will be asked to await the decision of the minister on the validity of the claim without assurance as to the timeliness of such a response. The government of Canada will need to quickly demonstrate its commitment to resolving these issues by ensuring not only that the center is fully resourced, but that their own internal processes are resourced commensurate with the need to eliminate the backlog of claims that each successive generation inherits from the past. As former Indian Claims Commission Co-Chair James Prentice remarked in May 2001 in a presentation to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs, “Canada is skilled in gradual, conservative institutional reform.” Only time will tell if Canada’s newest institutional change is truly an improvement over the past. It should be the hope of every Canadian, aboriginal, and non-aboriginal that it is.

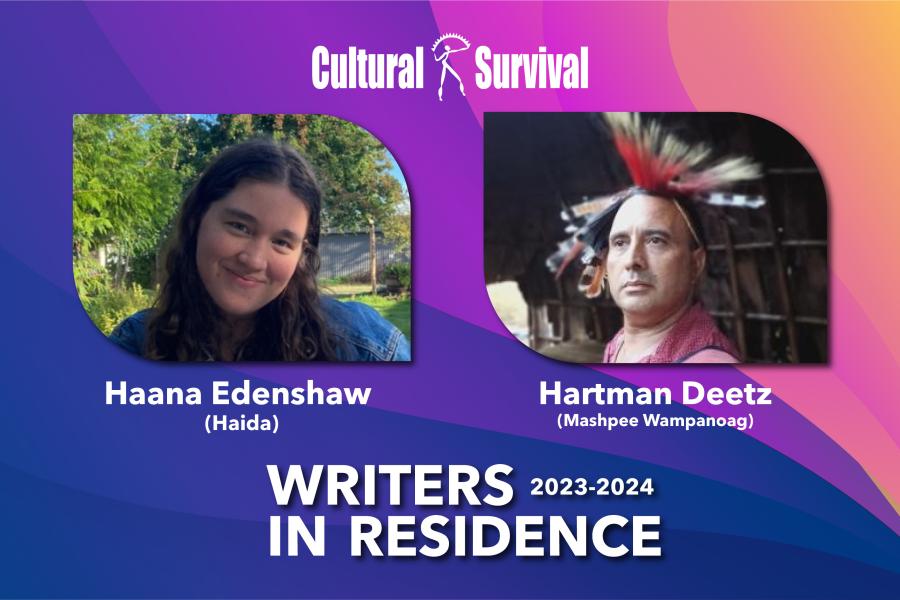

Kathleen Lickers is a Seneca from the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation in southern Ontario. She has practiced law exclusively in the area of aboriginal and treaty rights and has been legal counsel to the Indian Claims Commission for nearly 10 years. She continues to provide legal advice to the commission from her own law firm of Maurice Law, an aboriginal-owned and operated law firm with offices in Calgary, Alberta, and Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario.

References and further reading

Calder v. Attorney General of British Columbia [1973] S.C.R. 313.

DIAND. (1982). Outstanding Business: A Native Claims Policy-Specific Claims. Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services.

Kahkewistahaw First Nation 1907 Surrender Inquiry Report (1998). 8 ICCP 3.

Indian Claims Commission, Kahkewistahaw (2003, January). First Nation 1907 Mediation Report. Ottawa.

Bill C 6, An Act to establish the Canadian Centre for the Independent Resolution of First Nations Specific Claims to provide for the filing, negotiation, and resolution of specific claims and to make related amendments to other Acts. First Session, Thirty-seventh Parliament, 49-50-51 Elizabeth II, 2001-2002, 90191-2002-6-11.

Canada Department of Indian and Northern Affairs News Release 2-02156.

Chief Roberta Jamieson (2003, May 28). Presentation to the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, Hearings on Bill C-6, p 11.

P.E. James Prentice, co-chair of Indian Claims Commission (2001, May 29). Presentation to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs, p 15.