In global popular culture today, the superhero reigns supreme. Though Indigenous talents are becoming more visible in this alt-universe—actor Jason Momoa as Aquaman, Taika Waititi directing Thor: Ragnarok— characters and storylines still lean toward extraterrestrial themes and European-derived mythologies. Graphic novelist Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez, looking to change this status quo, decided to reach back to his own Taíno heritage from Puerto Rico in order to create a new kind of hero for his people and beyond: one whose powers and values come from a decidedly Indigenous foundation.

At least 70 percent of Puerto Ricans today are, in part, of Taíno descent, long affirmed by community systems and family lore across their island. The U.S. government-installed public education system, however, sought from its beginnings to counter that understanding. Indoctrinating a century’s worth of its territorial subjects in a stance that, contrary to their own oral histories, the Taíno people had actually been wiped out centuries ago, this curriculum asserted that Puerto Ricans therefore had no rightful Indigenous, historic claim over their colonized lands. Those who resisted, remaining steadfast in a Taíno-centered identity despite enduring marginalization for doing so, have been officially vindicated by recent advances in DNA testing that can not only confirm Amerindian ancestry, but actually pinpoint Taíno-specific gene markers distinct from other Native populations across the Americas. It is from this long suppressed history that La Borinqueña was born.

With three comic books published thus far in an ongoing series, this new superhero has received raves from the press and sparked a nationwide speaking tour for Miranda-Rodriguez. La Borinqueña is currently enshrined at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York (part of its Taíno exhibit), and stands together with Wonder Woman and Captain America in the Superheroes exhibit at the Smithsonian Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. Cristina Verán recently spoke with Miranda-Rodriguez.

Cristina Verán: Please explain the significance of La Borinqueña’s name.

Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez: La Borinqueña is a Puerto Rican superhero who is Indigenous to Borikén—the original Taíno name for Puerto Rico, meaning “land of the noble people.” This comic is rooted in that history, of the Taínos. Like most Puerto Ricans today, she has both Indigenous and African ancestors; being what some would call an “Afro-Taína.” I also wanted a character that was unapologetically patriotic, and “La Borinqueña” is the name of Puerto Rico’s first national anthem, written by Lola Rodriguez de Tió.

CV: La Borinqueña wears the colors and star of the Puerto Rican flag. What else inspired her look?

EMR: Like with Superman, her costume is form-fitting but not overtly sexualized; the only body parts you see are her hands and face. She has a muscular athletic body that, before even getting her superpowers, she [the young college student named Marisol who becomes La Borinqueña] actually developed on her own, riding her bike to school each day from Brooklyn to Manhattan.

CV: From where did you draw inspiration for the character, in terms of her motivations and values?

EMR: I was inspired by real women in my life—particularly Iris Morales, one of the original members and leaders of the Young Lords [the Puerto Rican-led civil rights and sovereignty-focused organization, which was counterpart to the Black Panthers and the American Indian Movement in the 1960s-70s], and Dr. Marta Moreno Vega, a founder of El Museo del Barrio and the Caribbean Cultural Center in New York City. And of course, my mother, my wife, and so many other women I grew up around.

CV: A departure from the sci-fi blockbuster stories dominating the superhero genre today, your storylines have a real world, social justice-centered focus. Why was this important to you?

EMR: The very first superhero comic books, which came from small, independent publishers, were always rooted in such themes. Only once they evolved into corporate-owned brands did things change: instead of actual human rights issues and humanitarian crises here on earth, they became more about battling intergalactic threats. I wanted to redirect the conversation from science fictional, fantastical narratives back to real issues, real people—my people.

CV: How do you identify, in terms of “your people?”

EMR: I identify as a Boricua, a term which defines me as a son of Borikén. Many nations and narratives—not only Taíno, but also from West Africa as well as from Spain—have shaped me into who I am today.

CV: To what extent was your Taíno heritage imparted in your family life?

EMR: I grew up in a very conservative Christian family. The Pentecostal church culture, imported to Puerto Rico from the United States, promoted a kind of Eurocentric spiritual colonialism that looked down on Taíno (and also African) spirituality as “idolatry.” They were always on the offensive against cultural practices not in line with evangelical teachings. My parents were also products of a school system, which, by design, repressed that knowledge.

The only aspect of our Indigenous heritage that my family did embrace was regarding our food. For example, we’d gather root vegetables from the ground—yuca, ñame, and yautia— to prepare traditional stews, or mash up to make pasteles. Without even being aware of it at the time, what we did, how we were doing it, was in fact the Taíno way.

CV: Given such negation, how did you find your way back to your heritage?

EMR: There’s a saying, “la sangre te llama”—the blood calls you. As a kid, I lived for a few years in Puerto Rico, in very rural communities—Ceiba, for example—made up primarily of jíbaros; that is, people living a traditional agrarian experience in the mountains and the rainforest, disconnected from modern life and the popular culture of the rest of the country.

There are mixed feelings about this term on the island. For some, it’s seen in a derogatory way, like being a “hillbilly” or a “hick.” Others, however, recognize that being a jíbaro, taking pride in that identity, asserts a direct connection to our Taíno ancestors. I’ve come to respect and embrace this view in my own way. I live in Williamsburg, Brooklyn now, where the people are often called hipsters. So, having also my own strong cultural identity and politics, I jokingly refer to myself as a “jíbster;” a hybrid jíbaro-hipster.

CV: From where does La Borinqueña get her superpowers?

EMR: I didn’t want her to come by them from getting bitten by a radioactive coquí [the tiny, beloved tree frog held up as the national symbol of Puerto Rico], and she wasn’t going to come from another planet. Instead, I wanted to connect to our Taíno heritage and its mythology.

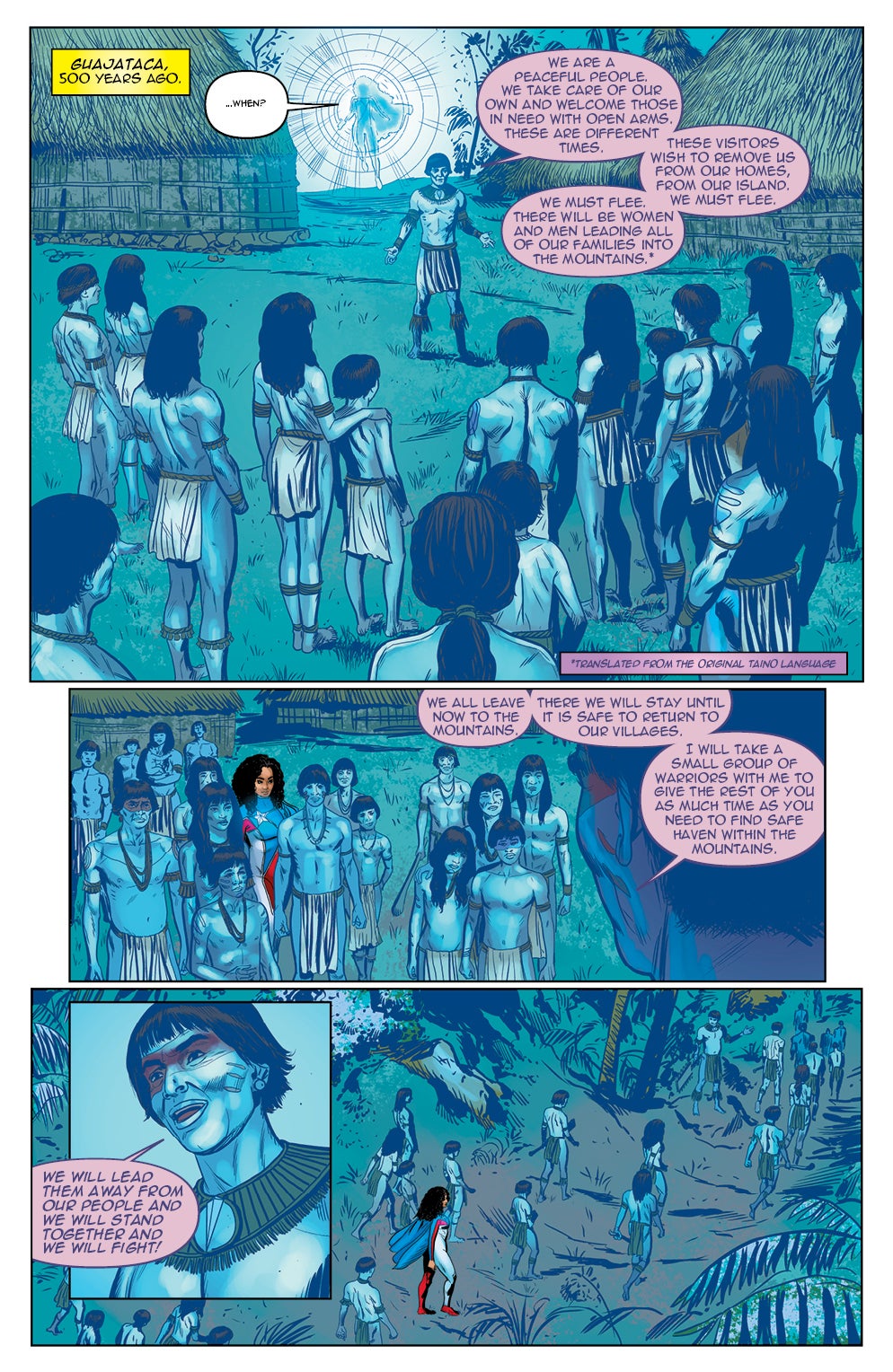

The stories center around [La Borinqueña communing with Atabex], the mother goddess representing the traditional matriarchal society, and also her twin sons, Yúcahu, god of the mountains and seas, and Huracán, god of the weather, maker of storms. [Interviewer’s Note: the English word “hurricane” comes from his name.]

CV: How does one represent a god in comic book form?

EMR: An image of Atabex found in ancient petroglyphs depicts her as a woman squatting, as if about to give birth, looking kind of extraterrestrial. I kept her that way, taking that original petroglyph image to the cosmos. For Yúcahu, meanwhile—whose throne is said to be atop a mountain in El Yunque rainforest—I rendered him as the mountain itself, drawn in the triangular shape of a cemí; the small, sculptural figures used to represent deities or the ancestral spirits of caciques, i.e., chiefs.

CV: Beyond the spiritual, mythological realm, this comic explores historical scenarios and figures. What should readers understand from this?

EMR: The hero’s origin story links the character to a Tainospecific history of not only resistance, but also resilience; those who stood up against the Spaniards, like Cacique Mabodamaca. They didn’t just let the colonizers take over. La Borinqueña’s story is a continuation of that narrative.

CV: With her popularity continuing to grow, what’s next for La Borinqueña?

EMR: I’ll continue publishing a new book in this series every year and a half; next in June 2020. I’m doing this all myself, without the resources of a Marvel or a Disney to publish more frequently. This series is primarily about connecting my activism to my love of comics, so instead of focusing energy around, say, making a movie, what I’m trying to create is a movement.

—Cristina Verán is an international Indigenous Peoples issues specialist consultant, researcher, strategist, educator, editor, and multimedia producer. Her work focuses at the intersections of human rights, political engagement, the arts, and community development. She is a longtime United Nations correspondent and was a founding member of the UN Indigenous Media Network.

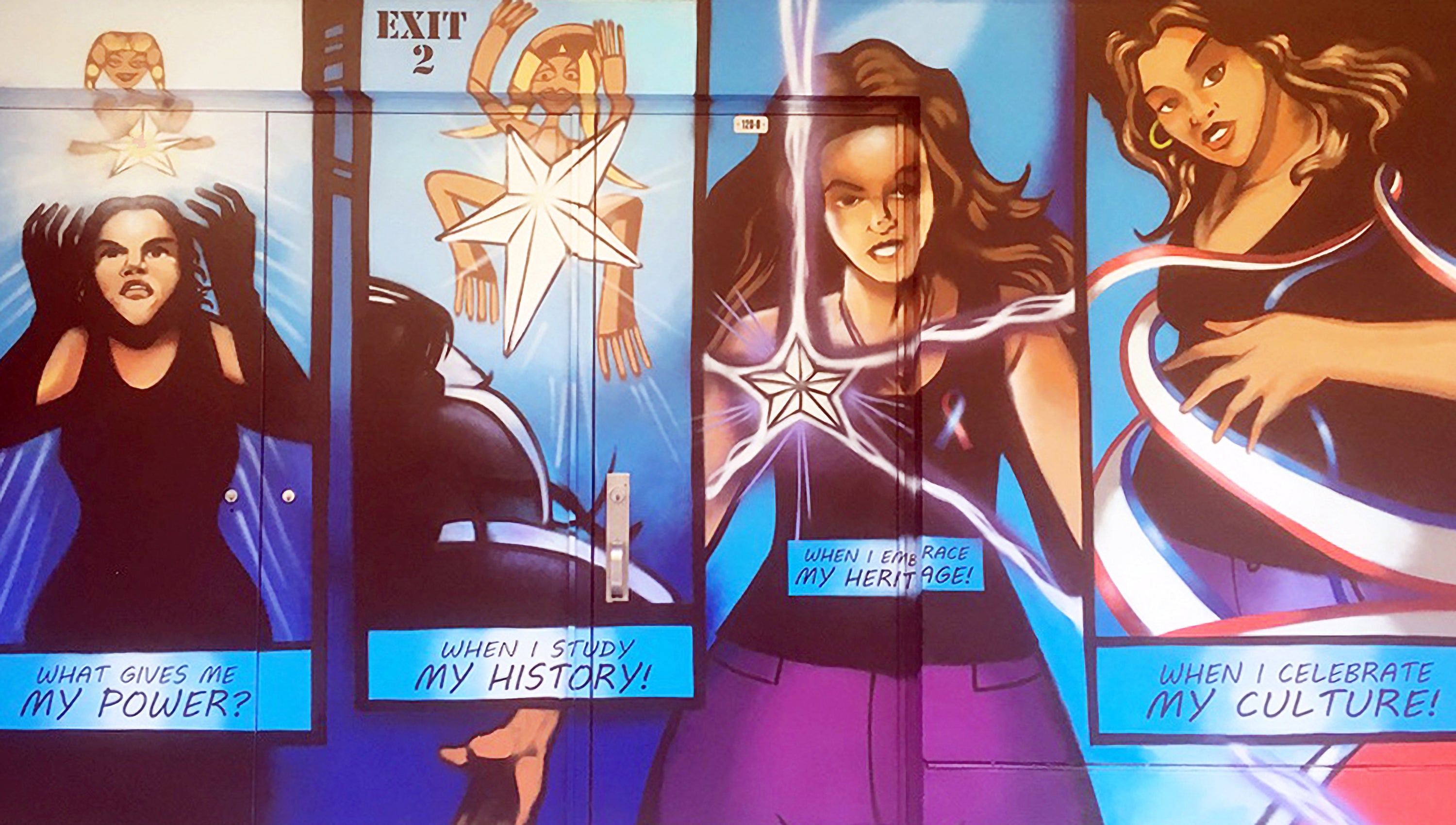

Photo of murals by Cristina Verán.

Images of comic pages courtesy of Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez.