Content Note: The following includes disturbing information on violence against Indigenous Peoples. We have strived to provide information on each individual, in celebration of their lives and work, without gratuitous detail on their deaths. Please note that the sources linked may contain further details and images.

In 2020, Cultural Survival documented 56 murders, 11 disappearances, and 23 violent attacks against Indigenous human rights and environmental defenders in Latin American countries where we work. Here, we remember some of the lives lost, celebrate their legacy, and call for justice.

Cultural Survival remembers, honors the lives, and mourns the violent deaths of the following Indigenous human rights and land defenders who were killed in 2020 in the Latin American countries we work in. We invite you to read about these individuals and to learn about their work and their communities, take action in support of the issues they devoted their lives to, and join us in calling for an end to impunity on these cases.

Attacks against Indigenous human rights defenders have surged at an alarming rate over recent years. Former UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Vicky Tauli-Corpuz, has called this trend a “global crisis." Globally, at least 331 human rights defenders were killed in 2020, according to Frontline Defenders. While Indigenous Peoples make up only six percent of the global population, they represent nearly one-third of the human rights defenders killed. More than three-quarters of the total murders of human rights defenders were in Latin America, making it the most dangerous region in the world to protect environmental, land, and human rights.

For example, in Colombia, despite the 2016 Peace Accords, there has been a massive wave of systematic violence against Indigenous Peoples, particularly against the Nasa Peoples in Cauca, with the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca labelling this a genocide. In Brazil, violence against defenders is often correlated with the illegal exploitation of Indigenous land by mafia groups, multinational corporations, and the government, frequently bankrolled by U.S. and other international financial institutions.

Cultural Survival’s Advocacy Program tracks violence against Indigenous human rights and environmental defenders within the framework of the UN Sustainable Development Goal 16.1, which seeks to significantly reduce all forms of violence and 16.3 which seeks to promote the rule of law and ensure equal access to justice for all. In this compendium, we seek to demonstrate that these cases of violence are not isolated instances, nor coincidence. They are evidence of an entrenched systemic problem that prioritizes government power and the wealth of industry over Indigenous Peoples’ lives, their sovereignty, their lands, and justice.

This list is not exhaustive, and we acknowledge there are many more cases that we were unable to profile here. Our database gathers cases as we learn about them through our direct community contacts, partner organizations and the media. It is not possible for us to document every instance due to a variety of factors: limitations to the publicity given to these events, language barriers, and our capacity. We strive to offer a sense of the scope of the problem and to draw attention not only to the acts that ended these defenders’ lives, but more importantly, to the powerful work they and their communities engaged in while they were living. Whenever possible, we elaborated on the lives, relationships, and work of the people described in each memorial.

Some of these murders have been highly publicized in national and international media, while others were only the subject of short news blurbs or social media posts at the time of the murder with little or no followup. Still others, we learned about through word of mouth from our contacts on the ground in different communities. This marginalization by the media is further evidence of the need for global attention to these murders and to the activists whose lives and irreplaceable work are cut short. Without this attention, it is easy for the killers and the governments, corporations, and criminal organizations who sponsor them to go unpunished.

Cultural Survival uses the data we have gathered here to denounce violence against Indigenous human rights defenders in human rights reporting to the United Nations Human Rights Council, UN Treaty Bodies, and other international human rights mechanisms. Through these processes we work towards harnessing international pressure to bring justice for these individuals, and an end to impunity for those who commit these crimes and the masterminds behind each case.

Cases are listed by country in alphabetical order, then chronologically by date of the incident:

Brazil

Celino Fernandes and Wanderson de Jesus Rodrigues Fernandes (Quilombola)

Photo via xinirim (Wanderson, left, and his father, Celino, right).

Celino Fernandes and Wanderson de Jesus Rodrigues Fernandes, father and son, were shot and killed on January 5, 2020. The men were leaders of the Cedro Quilombola Association. The murder took place in the Comunidade do Cedro in the municipality of Arari,170 kilometers from Maranhao`s capital, São Luís. Celino and Wanderson were part of a movement to reclaim public land surrounded by grilheiros, or land invaders/squatters.

According to a note from the Pastoral Land Commission, a nonprofit advocacy organization that assesses land status and conflicts and advocates for small farmers and landless people, Celino and Wanderson had denounced the agrarian conflict between the community and the grilheiros, who are surrounding public lands in the region and using electric fences to raise buffalo.

According to a document by the Commission, the families make their living from the area, located in the so-called natural floodable fields of the Baixada Maranhense, through fishing and animal husbandry. The document affirms these are “public lands of common use of the people” and constitute an Area of Environmental Protection in the State of Maranhão.

Shortly after the murders, a local news website reported that a police investigation was underway, though we have been able to locate further updates. Thirty-nine civil society organizations signed a letter denouncing the murder and expressing solidarity with the Fernandes family and the Quilombola community.

Joab Marins da Cruz, Marcos Marins da Cruz, and Francisco Marins da Cruz (Miranha)

Photo: Amazonia.org.br

Joab, Marcos, and Francisco Marins da Cruz of the Indigenous Miranha People from the Cajuhiri Atravessado Indigenous Land in the municipality of Coari, State of Amazonas, were murdered during the night of January 6, 2020. According to the police, Miranha teacher Joab was at his home when he was killed during a dispute over a gun. His father, Marcos, and nephew, Francisco, were killed while giving chase to the gunman. By January 13, 2020, suspects were in police custody.

The president of the Association of Indigenous Communities of Coari, Francisco Alves da Silva, said that relatives of the deceased had reported previous violent events to the police station of Coari and informed the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI), alerting that a tragedy could happen; however, no action was taken to prevent their deaths. He attributes their murders to conflict between local Indigenous and non-Indigenous people related to extractive chestnut-related production. Non-Indigenous people had established nut tree plantations without clear boundaries and without sufficient information provided to Indigenous Peoples in the area. It is common for local Indigenous Peoples to forage nuts on their own lands, and in this case, Joab, Marcos, and Francisco had unknowingly entered plantation land, a mistake for which they paid with their lives. FUNAI sent a special representative of the special federalized attorney’s office in order to mediate the conflict.

Zezico Guajajara, (Guajajara)

Photo via Zezico Guajajara on Facebook.

Zezico Guajajara was killed on March 31, 2020. Zezico was dedicated to the preservation of the natural reserve of his village, organizing a combat team to stop forest fires. He was also applying to be a city councilor to accelerate policies in favor of Indigenous Peoples. The region where he was murdered is known for grilhagem (illegal deforestation). Illegal logging activities and other exploitation of natural resources are made possible by State-sanctioned falsification of land title documents in order to illegally take possession of vacant lands or Indigenous lands. Zezico was engaged in a campaign to reconcile the vulnerable Indigenous communities, who, due to living in conditions of poverty and facing threats of violence, have been coerced into working for criminal logging companies. His fellow Indigenous leader, Olimpio Guajajara, described Zezico as “another fellow warrior—a man who defended life."

According to local leaders, Zezico and many other members of the Guajajara People had been persecuted by a logging mafia with ties with politics, business, and the local judiciary. The same organization is accused of murdering him and other Guajajaras in the past. The region of Arariboia is the most threatened land in Maranhao state, where Indigenous Peoples are regularly harassed and murdered because of their work defending their lands against illegal and State-sanctioned exploitation, with which international corporations and financial institutions are complicit. Requests for special protection from the State and FUNAI have been constantly denied. Further demonstrating the lack of State accountability for violence against Indigenous Peoples, of the 300 murders in the Brazilian Amazon tracked since 2009 by the Pastoral Land Commission, only 14, or 4 percent, were tried in court. In 2019, four Indigenous Brazillians were murdered within two months, including Paulo Paulino Guajajara, a relative of Zezico’s from the same community. According to the Brazilian Indigenous Peoples’ Association, in the last 20 years, 48 Guajararas have been murdered, most of them prominent leaders in the local community and great defenders of Indigenous rights. Just months before his death, Zezico sent a letter to FUNAI reporting the threats against his life, asking for help and protection. Nothing was done.

As of August 2020, two suspects have been arrested, although the investigation is ongoing and there may have been other perpetrators. NGO Survival International has released a petition seeking justice for Zezico’s and other defenders’ murders, as well as more broadly demanding protection for Amazon Guardians. Sign the petition here.

Ari Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau (Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau)

Photo via Cimi.org

Professor and environmental activist Ari Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, 33, of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau People, was murdered on April 18, 2020 on his land in Rondônia State. Amnesty International released a statement demanding “that the Brazilian authorities take all necessary measures to investigate the death of Ari Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau and to guarantee the right of his family and his people to truth and justice,” adding that “there is an urgent need to clarify whether his death is related to the series of invasions that his land has been suffering.”

The Federal Police suggested the death might have been an accident, but Ari’s community is familiar with the violence that accompanies land defense in their territory. The Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Peoples’ land has been subject to invasion, theft, deforestation, and land-grabbing via falsification of land title documents for years, with a marked increase in 2016 accompanied by government support. Threats to land defenders are also not new. Bitate Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, Ari’s nephew and the coordinator of the Jupaú Indigenous Association, said, “Ari was part of my Indigenous land surveillance team. He was a teacher in his community and was always at the forefront of surveillance actions. We are not safe, and while we protect the territory, we will live in that fear.” Ari left behind a wife and two children.

Original Yanomami and Marcos Arokona (Yanomami)

On June 12, 2020, two Yanomani men, Original Yanomami, 24, and Marcos Arokona, 20, from Brazil were shot and killed by illegal gold miners trespassing on their lands in the Amazonian region. Miners excavate the region in search of gold, with numbers reaching up to 20,000 miners illegally on the Yanomami lands. This trespassing into ancestral territory of the Yanomami infringes on the autonomy and land rights of the tribe and puts them in physical danger. Miners have also brought COVID-19 to some of the most isolated tribes in Brazil, including the Yanomami. According to Survival International, a UK-based Indigenous rights organization, the gold miners harass Indigenous Peoples in their own territories, threatening them with assault and violence. Original and Marcos were murdered by such trespassers. Junior Hekurari, head of the Yanomami Health Council, poignantly summed up the situation: “It is so sad to die on your own land.”

As a result of the murders, members of the Yanomami tribe have decided to mobilize and take public action to gain more land autonomy, creating a petition to appeal to members of the Brazilian government. Titled “Miners Out, Covid Out,” the petition aims to seek justice for the Yanomami and protect them from genocide. Following the murder, a court ordered the reopening of a monitoring station and the removal of miners to prevent the further dissemination of COVID-19.

Sign the petition to “Get the miners out now...and prevent the decimation of our people.”

Colombia

Jaiber Alexander Quitumbo Ascue (Nasa)

Jaiber Alexander Quitumbo Ascue, 30, was from the Nasa Indigenous People. On January 14, 2020, he was assassinated within the Toribío Reserve in northern Cauca while working his land. In response to his murder, the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC) declared, “The level of murders in Indigenous territories of North Cauca is alarming, especially considering that it has increased by seven cases in comparison to January 2019. Without a doubt, this is happening at an alarming rate for these communities.” Jaiber was not a leader with high visibility within his community, and according to Indigenous Senator Feliciano Valencia, the motives and those responsible for Jaiber’s murder have not been established. There has been rampant violence in the region due to illegal armed groups attacking Indigenous communities to gain control of their territories. Dissidents of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia and the National Liberation Army guerrilla groups, as well as gangs, are fighting over Cauca territory with the goal of using it for cocaine cultivation and drug trafficking. The Colombian Army has militarized the area and the violence continues despite the signing of Peace Accords in 2016.

Omar Guasiruma, Ernesto Guasiruma, and José Edgar Guasiruma (Emberá Chami)

Omar, Ernesto, and José Guasiruma were murdered on March 23, 2020, in the Bolivar municipality in Valle del Cauca department. The Guasiruma brothers were in their house abiding by the national quarantine rules of the COVID-19 pandemic when the crime was committed. Víctor Gasiruma Nacabera, a family member who was present at the crime scene, was also injured in the attack. Ernesto, 33, and Omar, 27, were leaders of the Emberá Chamí community and members of the Regional Cauca Valley Indigenous Organization. Ernesto worked to defend his community’s rights, which have been heavily impacted due to forced displacement. Omar worked to promote food sovereignty in his community, as well as to defend their territory from multinational corporations extracting natural resources and groups in armed conflict. In September of 2020, the suspect, Stiven Martínez, was placed in preventative detention.

On March 24, 2020, Amnesty International issued a series of recommendations to states in the Americas to ensure that the effects of the pandemic do not equate to the silencing of human rights defenders after the murders of the Guasiruma brothers. Just a few days earlier, on March 20, over 100 Indigenous groups and rural organizations called for a two-week ceasefire in the most conflict-heavy regions, including Cauca. Luis Fernando Árias, senior counselor at ONIC, announced restrictions for entry or departure from the reservation along with surveillance of the area by an Indigenous security force. On March 29, 2020, the National Liberation Army announced a ceasefire for the month of April to restart peace negotiations with the Columbian government.

María Nelly Cuetia and Pedro Ángel Troches (Nasa)

Photo: ONIC on Twitter

María Nelly Cuetia, 55, and Pedro Ángel Tróchez, 58, both Indigenous traditional doctors of the Nasa Indigenous Peoples in the Los Andes community of Corinto, Cauca, were assassinated May 28, 2020. María and Pedro, a couple who were both kiwe thë’j, or ancestral knowledge-holders, were holding a harmonization ritual when armed perpetrators broke in and forced them into a car. The National Indigenous Organization of Colombia announced that their bodies were found the next day and that the Páez Indigenous Reserve began investigations. The Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca announced in a press release: “This is an act of the greatest barbarity and contempt for our Nasa People’s life and survival. The assasination of elders is an act of destruction of our memory and knowledge. It is the final implementation of the extermination project that seeks to implement a scorched earth campaign.”

According to Senator Feliciano Valencia, who is also from the Nasa community, María and Pedro were respected as “wise Indigenous elders who [looked] after our community.” They were included in a report by the Washington Office on Latin America: “Advocacy for Human Rights in the Americas”, which was used to attract signatures for a “Dear Colleague” letter to former U.S. Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, to advocate for protections for social leaders.

Joel Villamizar (U’Wa)

Photo: Twitter CRIC Colombia Cauca

Indigenous U’wa leader Joel Villamizar was assassinated by members of the Colombian Army on May 31, 2020, in the Chitagá municipality near the Indígena Unido Reserve in the Santander department. Joel was the director of the U’wa Association as well as education coordinator in his community. The Association of Traditional Authorities and U’wa Councils (ASOU’WA) denounced the murder as part of a military operation that endangered civilians and violated their rights. The operation, carried out by members of the 30th Brigade of the Army’s Second Division, led to the capture of a guerilla leader, alias “Marcia,” of the National Liberation Army guerrilla group. According to ASOU’WA, Joel was falsely accused by the army as a member of the insurgent group. ASOU’WA called on national and international defense organizations to investigate the events as well as Colombian government and military parties who had a hand in the murder, qualifying it as an extrajudicial execution. This crime is also tied to the tactic of “false positives,” a term used in Colombia to refer to crimes in which the military murders civilians and presents the deaths as combat casualties with the goal of promoting the image of a successful war on drugs, funded by the United States.

Joel’s murder has been condemned by 16 national and international organizations, as well as EarthRights International, which pledged to bring the matter to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the UN Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. We have not located reports on further measures to hold his perpetrators accountable.

Jesús Antonio Rivera (Nasa)

Photo: Jesús Guillermo Pérez on Twitter

On June 13, 2020, Antonio Rivera, 32, from the Nasa community, was murdered in the Caloto municipality on Huellas Street on the Huellas reserve in the town of Caloto, Cauca. The Defense of Life and Human Rights Association of Indigenous Councils of Northern Cauca reported that the seven armed men responsible for the murder were captured and put on trial by the Indigenous guard, a traditional organization for territory defense, before being handed over to the national police. Jesús’ murder had been ordered by a lead dissident of the FARC guerrilla group, Fernando Israél Méndez, nicknamed “El Indio,” with the presumed goal of demonstrating his control over the area, for which a curfew had been implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Méndez has been wanted as the ringleader of an organized armed group responsible for various crimes against Indigenous and social leaders, including a 2019 massacre in Cauca, which killed Indigenous Nasa Governor, Cristina Bautista, as well as four other people. His capture, aided by the Indigenous guard, represents a rare win for justice for Indigenous Peoples who are victims of violent crimes in Colombia.

As of September 2020, all seven suspects have been convicted and sentenced.

Rodrigo Salazar (Awá-Kwaiker)

Photo: ONIC

On July 9, 2020, Rodrigo Salazar, an Awá Nation leader and auxiliary governor of the Piguambi Palangala Reserve, was murdered. According to the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia, “Rodrigo was a recognized leader and human rights and territory defender, as well as an advisor for the Indigenous security force of the Indigenous Unit of the Awa Nation.” Rodrigo’s leadership focused on promoting the replacement of illicit crops, as indicated in the Peace Accords.

Rodrigo was being threatened by illegal armed groups for his work as an Indigenous guard. For these illegal armed groups, the location of the town of Llorente made it a geographically strategic corredor for the production of cocaine and its transport to Ecuador. On August 18, 2020, Colombia’s District Attorney announced that the armed group Los Contadores would be held responsible for Rodrigo’s murder. The ringleader of this group, alias “Camilo 40,” had ordered Rodrigo’s murder when Rodrigo declined to remove a gate the community had put in place to restrict entry and protect their town from COVID-19. This gate also restricted the free movement of the armed group.

José Abelardo Liz Cuetia and Johan Rivera (Nasa)

Photo: José Abelardo Liz. Via Derechos Humanos Colombia.

José Abelardo Liz Cuetia, Nasa Indigenous radio journalist, and community member Johan Rivera were murdered on August 13, 2020. The leadership of the Páez Indigenous Reserve of Corinto, Cauca, denounced the repression and violence by the Colombian army that resulted in the murders and injuries of two other community members.

José was a member of Radio Payumat, which is a member of the communications collective We'jxia Kaa´senxi, or The Voice of the Wind, from the Corinth Indigenous Reserve. At the moment that shots were fired by the Colombian Army, José was reporting on the forced evictions of Nasa community members by the anti-riot military squad ESMAD, which is often involved in violently suppressing civilian peaceful protests. According to the Asociación de Cabildos Indígenas from the north of Cauca, and confirmed by video coverage of the event, members of the military fired multiple rounds from assault rifles at the villagers. The Office of the UN Human Rights Commission in Colombia condemned the crime and called for investigations and justice; Forbes has reported that as of January 4, 2021, there has been no progress in the investigation.

Confrontations against the Indigenous communities in the area had been taking place for several weeks at the same time as grassroots gatherings called “Liberation of Mother Earth.” Organized by Indigenous communities in Cauca via the Regional Indigenous Council of Colombia, Liberation of Mother Earth is characterized by a commitment to create a world economy outside of the capitalist system that champions human rights over profits. Read Cultural Survival’s full story of Jose’s activism and his murder here.

Miguel Tapí (Emberá Dóbida)

Photo via Tercer Canal

Miguel Tapí, 60, a well known Indigenous Emberá Dobida leader of the Del Río Valle zone in Bahía Solano, was murdered on December 3, 2020. Miguel was the governor of the El Brazo and Bacuru Purru Indigenous communities, and was recognized as one of the most important spokespeople in the region. His body was found the day after some hooded men burst into Miguel’s home and took him to the river. These men had identified themselves as members of the illicit organization Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, which is also known as the Gulf Clan. After the murder and in the face of the ongoing threat, 906 people from 195 Indigenous Emberá families from the El Brazo, Posamanza, Boro Boro, and Bacurú Purrú communities were displaced from their territories. These families were able to return on January 20, 2021, thanks to coordination with State authorities.

On January 13, 2021, the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia publicly denounced the murder, calling on the Colombian Attorney General's Office to prioritize the investigation into those responsible.

Massacre on Awá People

According to initial reports, on September 26, 2020, five Awá Nation natives were murdered at the hands of illegally armed groups. The identities of these five individuals have not yet been revealed. It was initially broadcast that 40 townspeople were kidnapped, among them “two or three minors, young people, women, and adults.” According to another report released by the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia, four, rather than five, people were killed, including an Awá person from Inda Sabaleta and a minor from Awá de la Brava. The same report mentioned three missing people, rather than 40, with someone from the Inda Sabaleta Reserve among them. No recent reports have been found that clarify the number of deaths, although the governor of Inda Sabaleta, Neider Sevillano, announced that no kidnappings had taken place after verifying the population. The lack of clarity in this case highlights a failure to prioritize official investigations of cases of violence against Indigenous Peoples.

The acts occurred on Indigenous Inda Sabaleta Reserve in the Tumaco municipality of the Department of Nariño during a confrontation between armed groups Los Contadores and the Oliver Sinisterra Front over attempts to take control of the Inda Sabaleta territory. Community members were displaced for fear of confrontations. This violence took place in the context of massive forced displacement of the community in 2007. Fearing a repeat of this history, community leaders requested urgent actions to protect their fundamental rights to life and territory.

Governor Sevillano asked for aid in increasing training and reinforcements within the Indigenous Guard to avoid bringing in military reinforcements. The Indigenous Awá Nation of the Putumayo and Nariño departments have been under precautionary measures established by the Interamerican Commission of Human Rights since 2011 due to multiple murders and threats against the population. Since then, only three of the nineteen plans of collective protection have been implemented. Tumaco has one of the highest cocaine production rates in Colombia. Because of this, this municipality has some of the highest displacement rates in the country.

Massacres in Cauca

Photo: Eduardo Pino Julicue, via Jallalla Juventud

On December 5, 2020, at least six Indigenous individuals were murdered in three crimes that took place in the Cauca region. In Santander de Quilichao, in the north of Cauca, a confrontation between two hit men and the community resulted in the deaths of Emerli Basto, brothers Fernando and David Tróchez, and Carlos Escué. Carlos was a local youth coordinator at the Munchique Los Tigres Reserve. He promoted autonomous territorial control in Quitaperaza and La Esperanza, and was also a singer in musical group Intentos de Amor. Fernando, a reinstated war veteran, had signed the peace accords with guerrilla group Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. No further information was found about Emerli and David.

Hours before these crimes, Eduardo Pino Julicue, 31, was murdered in Caloto. Eduardo was the son of the previous advisor for the Association of Indigenous Councils of Northern Cauca, Luz Eida Julicue. The same day, Juan Calos Petins was also murdered at the Indigenous Tálaga Reserve. Juan Carlos was a well known Indigenous Nasa individual of the Nega Cxhab-Belalcázar Reserve, located in the Páez municipality. Two days before, Colombia’s High Commissioner of Peace, Miguel Ceballos, had visited this municipality in compliance with commitments to the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC) to implement the Cauca Social Plan, a government initiative on issues of coexistence, peace, and legality in the region. Juan Carlos worked to provide support services for media and internet use. He also collaborated in community processes in which individuals work on a farm in exchange for food in the Nasa Nation of the Páez municipality.

In response to these massacres, CRIC criticized President Iván Duque’s acts and called upon human rights defense entities to demand that the Colombian government guarantee life and fulfill the demands of the peace accords. A December 2020 UN update included the massacre in their review of 2020 murders in Colombia. The article mentions the Nasa People as being particularly targeted and reports that 24 other Nasa leaders received death threats on December 5 in addition to the murders.

Costa Rica

Jerhy Rivera Rivera (Brörán)

Photo: Jerhy Rivera

Costa Rican Indigenous leader, Jerhy Rivera Rivera (Brörán) was shot by an armed mob on the night of February 24, 2020, in the community of Mano de Tigre, San Antonio, in the titled Indigenous Territory of Térraba, Puntarenas province, marking the second death of Indigenous land defenders in the country in less than a year. This murder occurred two weeks after Bribri leader Mainor Ortiz Delgado survived a shot in the right thigh in the Rio Azul Community of Térraba. Since 2010, in the face of government inaction, Indigenous communities in Costa Rica have been re-occupying lands within 24 territories belonging to them under the 1977 Indigenous Law. A Bribri leader, Sergio Rojas, had led efforts to recover the lands in his Indigenous territory of Salitre until he was murdered on March 18, 2019, a crime whose perpetrator remains unidentified despite numerous calls for investigation.

The attack against Jerhy did not come without warning. The Indigenous Peoples’ National Front reported that two nights before the murder, they sent out an early warning communication to government authorities and the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples regarding a recent mobilization of non-Indigenous people invading the newly recovered Indigenous territories of Térraba, Crun D'bonn, and Cabagra in Palmira. “Early warnings about the growing tensions in Térraba were once again met with an ineffective response by the State,” Vanessa Jiménez of Forest Peoples Programme, told The Guardian. “The government either can’t or won’t protect the Bribri and Brörán from violence.” Jerhy was the subject of an earlier attempted murder, but his attacker was never jailed. He was brutally assaulted in September 2013 while searching for a cell signal to report to authorities that non-Indigenous people were conducting illegal logging on Indigenous territories.

Since 2015, the Bribri and Brörán communities have been subject to precautionary protection measures ordered by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. This distinction means that the government of Costa Rica is responsible for ensuring the physical protection of the individuals within these communities. In a press release, the traditional Indigenous governance council, Consejo Ditsó Iriria Ajkonuk Wakpa, declared, “We denounce the State for its complicity in this assassination, for not abiding by the Precautionary Measures ordered by the Inter-American Court for Human Rights, which are guaranteed to the Brörán community of Terraba and the Bribri of Salitre. We also denounce the President of Costa Rica, Carlos Alvarado Quesada, who aims to delay the process of land and territory recuperation while failing to carry out evictions necessary to bring peace and territorial integrity to Indigenous lands. We will not be deterred in the defense of our land rights.”

José María Villalta, a member of the Frente Amplio political party, demanded justice for Jerhy’s murderers on the one-year anniversary of his death, calling it a “flagrant crime.” He also called out the State for not taking action despite the fact that the suspects have been identified. As of September 27, 2020, there were multiple news stories regarding the release of alleged suspects from custody.

Read Cultural Survival’s full length article on Jerhy Rivera here.

Chile

Alejandro Treuquil (Mapuche)

Photo via Mapuexpress

Alejandro Treuquil was an Indigenous leader and activist from Chile. On June 4, 2020, in the southern Chilean town of Collipulli, Araucanía, unknown outsiders attacked Alejandro and other members of the Mapuche community, killing Alejandro with gunshot wounds. Fourteen other Mapuche community members sustained injuries.

A member of the We Newén community of the Mapuche Peoples, Alejandro advocated for land rights and autonomy for his people in the region of Araucanía in southern Chile. The Mapuche are the most populous Indigenous community in Chile, and their lands have been divided across Chilean and Argentine territory. As a werkén, or community leader, Alejandro represented the goals of the Mapuche in their standoffs and encounters with the Chilean police force, the carabineros. Chile has a history of animosity and exclusion towards Indigenous Peoples. It is the only South American country to exclude Indigenous Peoples from its constitution, one of the reasons Indigenous Peoples supported the successful 2020 referendum to establish a new constitution. Chile also continues to weaponize a 1984 Pinochet-era anti-terrorist law against Indigenous communities and political dissidents, making it easier to arrest human rights defenders without due process.

The carabineros have a history of targeting Mapuche Peoples: in 2017, they arrested eight Mapuche leaders on what was later discovered to be falsified evidence. Again in 2017, police forces tear gassed an area close to a Mapuche school as part of their criminal investigations. This police force has illegally occupied ancestral lands of the Mapuche, and Alejandro was active in denouncing their presence. A 2017 estimate found that the whole Mapuche nation holds ownership of less than 500,000 hectares of their ancestral lands, compared to the nearly 2,000,000 hectares of their ancestral land currently owned by forestry corporations. After carabineros set up State-protected areas surrounding these ancestral areas as a way to keep the Mapuche People out, tensions between the Mapuche and the police forces progressed, culminating in the attacks of Indigenous rights activists, including the case of Alejandro.

In 2018, Cultural Survival documented systemic State violence and discrimination against Mapuche human rights and land defenders in a report to the UN Human Rights Council via the Universal Periodic Review process. This obligated Chile to “ensure conciliation between the government and Indigenous groups to address escalating violence in the Araucanía region.” The attack on Alejandro and his community represents Chile’s failure to ensure the safety of Indigenous Peoples despite accepting clear recommendations.

On September 29, 2020, police arrested alleged perpetrator Carlos Cristopher Muñoz Salamanca when evidence of his plan was found in WhatsApp chats to a friend. A possible motive for the murder may have been a conflict over a robbery of Salamanca’s uncle that Treuquil was alleged to be planning. Ana Karen Loayza Muñoz was also arrested and charged in October for her participation in the murder.

Guatemala

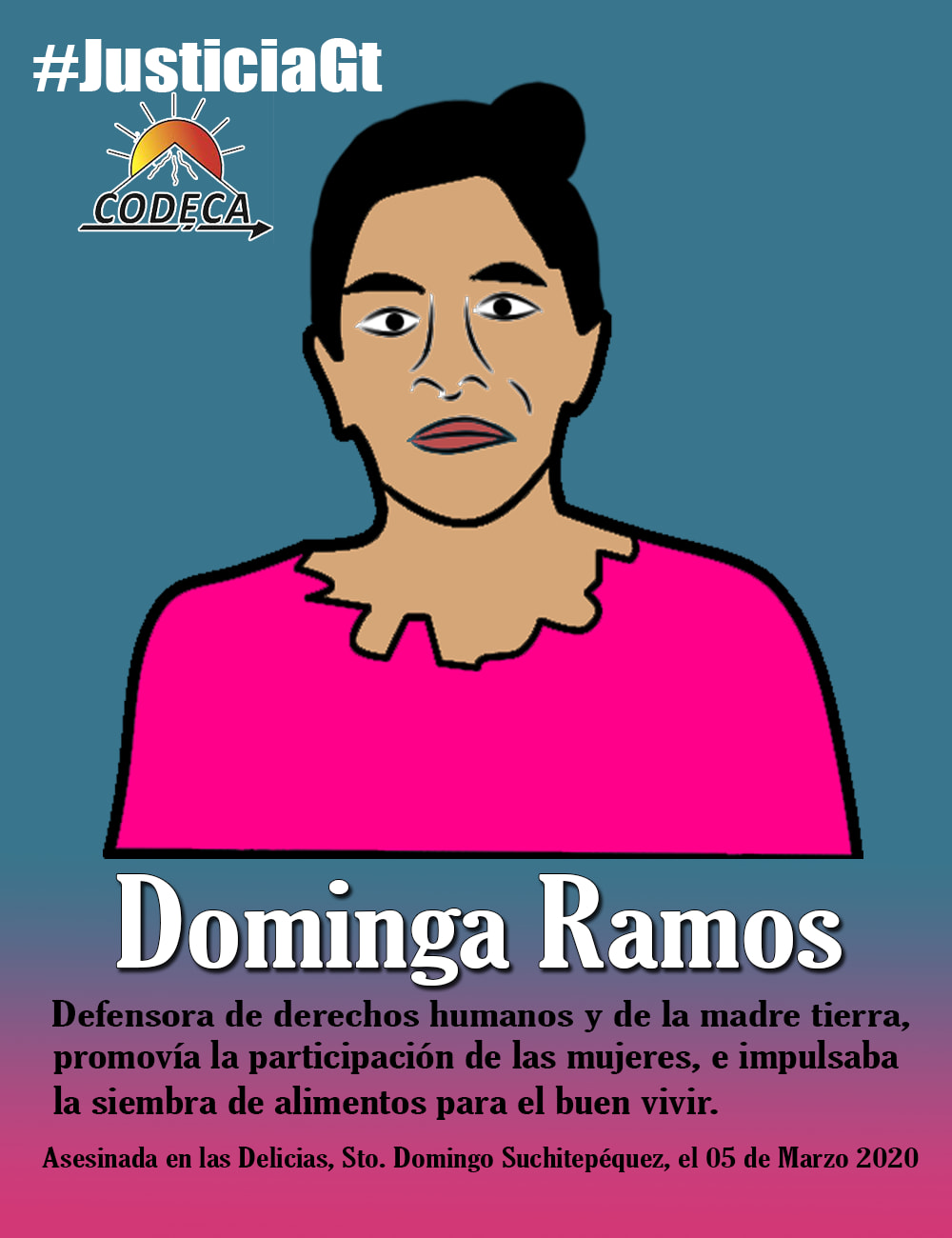

Dominga Ramos (K’iche’)

K’iche Maya Indigenous rights defender, Dominga Ramos, was shot and killed by an unknown assassin on the afternoon of March 5, 2020, in front of her daughter-in-law and grandchildren. She was a member of the Committee for Campesino Development, an Indigenous-led grassroots organization that fights for Indigenous and campesino rights in Guatemala and whose main goals include improving working and living conditions of the rural poor, fighting against exploitative energy companies, and political advocacy. Dominga was particularly known as an activist in the movement to nationalize the electric power industry due to the “excessive and arbitrary” charges levied by the electrical company ENERGUATE. She is also remembered as a mother, grandmother, and wife.

Dominga is only the most recent CODECA member to be violently targeted for her politics; 10 members of CODECA were killed in 2019, and 7 were killed during a 4-week period in 2018. We have not been able to locate information on further investigation into to her murder.

Domingo Choc (Q'eqchi)

Photo via Monica Berger

Domingo Choc Che, Maya Q’eqchi’ spiritual guide, scientist, and master of traditional medicine, was brutally murdered on June 6, 2020, in a violent attack against his cultural practices.

“Tata” (Grandfather or Elder) Domingo was known nationally and internationally for his work. In addition to being an Ajq’ij (spiritual guide), he was an Aj ilonel, a specialist in Maya medicine. “An Aj ilonel is, in the Maya medicine model, a person who has a gift that allows him to protect the health of people and family. It is someone who has knowledge of plants, lunar cycles, and knows the time to identify, collect, and prepare medicinal plants. His community function and role is to protect the community. He is a person of great respect, and if you need his advice, he can offer it, be it to individuals or to families,” explains Carlos Morán Ical, Poqomchi’ investigator, psychologist, and Ajq’ij.

Alongside colleagues, Tata Domingo was contributing to a project documenting the traditional medicinal plants of the Guatemalan department of Petén. The project is a collaboration among multiple universities, including University College London, Zurich University, and the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala. Since he was a boy, Domingo had a relationship with ancestral Maya ethnobotanical knowledge, carrying “the legacy of his paternal grandparents,” said Héctor Quib, a colleague from the Association of Spiritual Guides. After a group of residents from Chimay, San Luis, Petén, Guatemala accused Domingo of witchcraft and of being responsible for the death of a townsperson, four individuals doused him with gasoline and set him on fire. The case will go to trial on April 29, 2021. The person who filmed the video accusing Domingo of practicing witchcraft has been released, while three other people associated with his murder will be tried and another three are under investigation.

Read Cultural Survival’s story celebrating Tata Domingo’s life and demanding justice for his murder here.

Alberto Cucul Choc (Q’eqchi)

Photo: Twitter of Mongabay Latam

Environmental defender Alberto Cucul Choc, Q’eqchi’ Maya from the community of Pie del Cerro in Cobán, Alta Verapaz, was shot and killed on June 8, 2020 on his way to work as a park ranger for Guatemala’s Laguna Lachua National Park. This is a dangerous job in the region, as Laguna Lachua, along with other national parks, is often at risk of illegal looting of natural resources by mining companies. Also operating in the region are drug trafficking groups who threaten those who interfere with their routes. Alberto had worked as a ranger protecting the national park for 13 years.

Medardo Alonzo Lucero (Ch'orti')

Photo via Peace Brigades International Canada

Medardo Alonzo Lucero was murdered on June 15, 2020 in Olopa, a municipality in the department of Chiquimula. His body was found with signs of violence the next day. Medardo was a Maya Ch’orti’ defender of land, natural resources, and Indigenous rights. According to the community authorities, he was active in the peaceful organized effort against mining in the Olopa region, which led to his murder. According to PDH Guatemala, “The Indigenous authority of the community reported that the death is linked to the defense of the territory and the fight against mining.”

The Indigenous Ch’orti’ community has led various peaceful demonstrations to put a stop to mining operations, as the license of mining company Cantera Los Manantiales was granted before the Indigenous community had the opportunity to implement their right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent. In February of 2019 the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources sent a report stating the company did not meet minimum environmental requirements, leading the Ch’orti’ Council of Olopa to file an appeal with the Guatemalan Supreme Court of Justice. The company responded by criminalizing and defaming the Ch’orti’ population.

Medardo’s brother, a Ch’orti’ community leader, has worked to seek justice for the murder and received death threats from people linked to the mining company. There have been many other threats, attacks, and harassment against land defenders working to put a stop to the mining operations in Olopa. Medardo’s murder was the second murder of a land defender in Olopa in recent memory; Ch’orti’ environmental activist Elizandro Pérez, who had led resistance against the mining company, was killed in 2018.

Read Cultural Survival's full piece on Medardo and his community's struggle here.

Carlos Mucu Pop (Q'eqchi')

Photo via Setul Sayaxché Petén

Carlos Mucu Pop, a Q’eqchi’ leader in the Santa Rosa, Sayaxché community in the Department of Petén, was murdered on August 16, 2020. Carlos fought to defend the rights of those in his community and had been a candidate for mayor of Sayaxché. Carlos was also a member of Asociación Comunitaria Multisectorial del Monitoreo Comunitario en Salud y Apoyo a Migrantes, a Guatemala-based organization that works with other groups to monitor violations of migrants’ human rights at the Mexican and Guatemalan borders. The route through Petén is one of the most used migratory routes in Central America. In recent years, families in these regions have housed migrants, giving them information about other routes, medicine, and a place to regain strength for the rest of their journey to Mexico or the United States.

In August 2020, Unit for the Protection of Human Rights Guatemala and the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders referred to Carlos’ murder in a condemnation of Guatemala’s lack of progress on the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ 2014 order requiring Guatemala to develop policies for the protection of human rights defenders.

Honduras

Vicente Saavedra (Tolupán)

Photo via Gilda Silvestrucci

Vicente Saavedra was a Tolupán leader. His body was discovered on January 10, 2020, several days after his disappearance. He had been shot several times. Vicente was a delegate at the local Catholic church and was known as a peaceful individual in his community who did not start trouble with anybody. His community has been subject to extreme violence due to their defense of their territories, with at least 70 incidents taking place in 2019 alone. The motive for his murder has not been determined and further information about investigations has not been located.

Antonio Bernárdez (Garífuna)

Photo by CESPAD

Antonio Bernárdez was found murdered on June 21, 2020, after having been missing for six days. Antonio, 71, was a Garífuna leader from the Punta Piedra community in Honduras. There has been continuous violence against Garífuna leaders by land invaders in the region for decades related to violent land grabs.

The area of Punta Piedra was invaded in 1992 by a group of non-Indigenous farmers and ranchers driven by General Castro Kabus, and has since had little stability as conflict emerged between the Garífuna and the invaders. The Garífuna community has been asking that the invaders be relocated since the early 1990s. The case was presented to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2003, which ruled in favor of the Garífuna community in 2015. However, the government of Honduras has refused to acknowledge this and comply with the ruling. Antonio’s relative, defender Felix Ordoñez Suazo, was murdered in 2007. Just weeks after Antonio’s murder, four Garífuna men were kidnapped by armed men in police uniforms, sparking protests in the Garífuna community.

Carolina Valentín Dolmo, (Garífuna)

Photo via Juventud y Cultura

Carolina Valentin Dolmo, 32, was found dead in the Danto River on November 24, as reported by the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (OFRANEH), who requested an urgent autopsy to clarify the cause of her death. OFRANEH notes that her death comes in the context of a series of violent attacks against the Garífuna community. Carolina was the daughter of a director at the Garífuna community radio station, Radio Comunitaria Wagia. The Garífuna news blog Wa-Dani reports that her case is the 18th violent crime against Garífuna in Honduras during 2020.

International human rights organizations have called on Honduran officials to investigate her death, although the victim’s father denounced on January 24, 2021 that his daughter’s case has not been investigated or resolved.

Felix Vásquez (Lenca)

Photo: Peace Brigades USA

Felix Vásquez was a Lenca environmental activist and land defender. On December 27, 2020, Felix, 70, was murdered in front of his family by armed masked men. He and other community leaders had been subject to intimidation after tension related to land disputes with a local farmer. Felix had reported death threats related to his work, as well as being followed in the weeks before his murder. Since 2017, Felix had filed complaints with national authorities regarding political persecution as a result of his environmental work.

Felix had defended Indigenous territory rights since the 1980s and was known around Honduras for his opposition to extractive projects like mines, wind farms, and dams. He also fought for communities’ rights to ancestral titles to land and for the rights of rural workers. Felix had recently announced his plan to run for Congress as part of the progressive LIBRE Party in the 2021 elections. Another of his concerns was landowner occupations in nature reserves such as the El Jilguero watershed, which would harm more than 300 Indigenous families.

Felix was Lenca, an Indigenous People to which Berta Cáceres, an environmental defender whose highly publicized murder took place in 2016, also belonged. Honduras is one of the world’s most dangerous countries for environmental activists, with the highest number of environmentalists per capita killed. A military coup in 2009 resulted in the installation of a new government under which hundreds of environmental defenders have disappeared, been murdered, or criminalized. Honduras’s National Human Rights Commission condemned the killing and said it would investigate. The commission had requested protective measures for Vasquez in January 2020, but they were never carried out. Yuri Mora, spokesman for the Honduras prosecutor’s office, said that the office on ethnic groups and cultural patrimony was investigating Vasquez’s murder, and that investigators had executed searches and were about to call people in to make statements.

Jose Adan Medina (Tolupan)

Photo via FETRIXY

Jose Adan Medina was found shot to death in the community of El Volcan, Honduras on December 27, 2020. Medina was a leader of the Candelaria tribe of the Tolupan Indigenous community and a prominent figure in disputes with loggers and landowners in the mountainous areas of Francisco Morazan and Yoro. The leader of Yoro Indigenous organization Federación de Tribus Xicaques de Yoro (FETRIXY) told Reuters that Medina had reported threats against him to the attorney general’s office, following disputes with local loggers and landowners. “[Medina] was murdered for fighting in the defense of the land of the Candelaria Tribe where landowners and loggers have occupied our lands. He was shot dead by at least four men when he came back from working his land, growing corn and beans,” Noe Rodriguez told Reuters. FETRIXY called for justice for Jose on their Facebook page.

On February 10, 2021, Honduran officials issued a statement that they had carried out a raid capturing three men allegedly responsible for this act of violence. The press release from the Attorney General’s office discounted political motives for Medina’s targeting, attributing his shooting to his having filed a complaint against his attackers for theft some days prior.

Mexico

Antonio Montes (Rarámuri)

Photo: Twitter account of Educa Oaxaca

Antonio Montes Enríquez, 43, was a Rarámuri community leader and activist in Bosques de San Elías Repechique, Chihuahua. He was murdered on June 6, 2020. An arrest warrant has been issued as the attack was seen by multiple witnesses. His death has been linked to his fight against the construction of an airport on Rarámuri land and in defense of their territory.

Antonio’s community is made up of around 130 Rarámuri families living in an area comprising just under 30,000 acres. Days before his death, Antonio had been planning a protest at the Barrancas del Cobre airport, where he planned to denounce the misuse of a trust fund created in 2016. This trust, which offered 65 million pesos to the Rarámuri community, was formed to compensate for the destruction of Rarámuri land used for the creation of the airport. However, the trust’s technical committee used legal loopholes to ensure the Rarámuri community would be unable to access the trust for years. The trust money was meant to be used for community benefit, including cultural and environmental preservation projects. In addition to his activism related to the trust, Antonio also opposed illegal logging encouraged by organized crime in the region. On February 8, 2021, radio station La Ranchera de Cuauhtemoc reported on their Facebook page that Antonio’s alleged killer has been taken into police custody.

Óscar Eyraud Adams and Daniel Sotelo (Kumiai)

Photo: Óscar Eyraud Adams connecting irrigation tubes in his dry fields. Photo via friends of Óscar via Pie de Pagina.

Óscar Eyraud Adams was murdered on September 25, 2020, in Tecate, Baja California. A water rights activist, Óscar protested against the privatization of water in the area by transnational water companies during months prior to his murder. In the month prior to his death, Óscar had publicly denounced corruption in Mexico’s National Water Commission (CONAGUA) for denying the Kumiai the right to dig a well to irrigate crops while issuing concessions to private beer and wine companies including Heineken and LA Cetto.

In a video report published by Grupo Reforma on August 31, Óscar is shown standing in front of arid lands where fruit trees had previously grown, saying, “All of this disappeared...because we don’t have enough water. We do not have a permit to extract water with a well, and we would like Blanca Jimenez, the head of CONAGUA, to consider us before the large water consuming companies. Heineken has more than 12 wells, and the aquifer is overexploited.”

According to a press release from the National Indigenous Congress of the Northwest, Óscar was working towards the Kumiai community’s self-determination and the right to use water concessions. Óscar “was commissioned by his community, Kumiai Juntas de Nejí, to investigate rights to self-determination and autonomy. He investigated international treaties that would support his people, who are endangered due to lack of water,” reported Pie de Pagina.

Óscar was also vocally opposed to the Trump Administration’s border wall between the U.S. and Mexico, advocating to bring a case to the International Court of Justice in the Hague, the UN, and to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Just days later, on September 27, 2020, Óscar’s brother-in-law, 32-year-old Daniel Sotelo, was shot and killed by an armed group in his family-owned grocery store in Tecate. He was taken to the hospital where he died in emergency care. Like Óscar, Daniel belonged to the Kumiai Indigenous People. The deaths of Óscar and Daniel adds to the list of Indigenous environmental defenders who have been attacked or criminalized for their advocacy in the State of Baja California, such as well known Kumiai activist Aurora Meza, who was unjustly imprisoned in 2014 after false accusations by a local rancher. In the face of this violent repression, the Kumiai People continue to seek rightful self-determination.

Witnesses to Óscar’s murder reported that the perpetrators were a group of five gunmen wearing tactical gear. The Citizens’ Human Rights Commission has said that the murder was intended to silence his work as an Indigenous defender and advocate for water democratization, accusing the National Water Commission and Heineken Brewery of the crime. The Citizens’ Human Rights Commission called on Baja California Governor Jaime Bonilla Valdez not to let the case go unsolved. We have not located further information on the progress of the case.

Juan Aquino González (Nahua)

Juan Aquino González, Nahua environmental activist and Papalutla community member, was murdered on October 28, 2020, while in a pickup truck at the entrance of his community. As of March 2021, it is unknown who is responsible for his murder. Juan managed an Indigenous-owned ecotourism park and was an activist and legal representative of the park and other conservation areas, according to environmental groups. The Reserva Ecológica del Cerro de Tecaballo de Guacamayas y Murciélagos and the Reserva Ecológica de Cazadores are ecological reserves intended to protect the region’s fauna including birds, bats, hares, and wild pigs. Juan was a founder of these reserves. He was also a representative of the Indigenous Sector of the Guerrero Nucleus and Consultative Council, a part of the United Nations Development Programme. We have not been able to locate further information on the investigation or arrest of perpetrators.

María Agustín Chino, Amalia Morales Guapango, José Benito Migueleño, and Miguel Migueleño (Nahua)

On December 19, 2020, María Agustín Chino, Amalia Morales Guapango, José Benito Migueleño, and Miguel Migueleño, four Nahua members of the Indigenous and Popular Council of Guerrero-Emiliano Zapata (Cipog-EZ), were murdered. Cipog-EZ is made up of 22 communities that have been active in defending their lands against organized crime in the region. About a year ago, Cipog-EZ had dug trenches on the perimeter of their territory to defend themselves and their land against armed attacks by drug trafficking cartels. The land is in high demand by organized crime groups such as Los Ardillos because it could be used for drug and weapon routes, as well as opium poppy planting. The murders of María, Amalia, José, and Miguel may have been a response to Cipog-EZ having removed fencing installed by Los Ardillos. Mexico’s Attorney General’s office has identified brothers Celso and Jorge Iván Ortega Jiménez, along with another brother who works for the Democratic Revolution Party, as the leaders of Los Ardillos. The community currently has a case pending with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. In October 2020, Cipog-EZ met with Mexico’s sub-secretary of Human Rights, Population, and Migration, Alejandro Encinas, to inform him of their situation with the cartel. However, no action was taken before the murders took place in mid-December.

In a statement about these four murders, the communities of Cipog-EZ wrote, “COVID-19 is the least of our worries; they are killing us like this, like animals, without anyone listening, without anyone doing anything… no struggle for true liberty and justice has been easy.” The communities of Cipog-EZ met on December 27 with the representatives of the Commission on Human Rights Defense and the Republic’s General Prosecutor to demand justice. In total, 28 Indigenous community members have been murdered in the past 2 years with several others missing or injured. The blame for this violence and massacre, the communities say, falls on the Los Ardillos cartel. However, many relatives have failed to report the murders due to fear of deadly repercussions from Los Ardillos. Cipog-EZ demanded that the president of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, intervene due to lack of action coming from previously contacted government entities and organizations. To date, the case has yet to be processed in court.

Peru

Arbildo Meléndez Grandes (Kakataibo)

Photo via AIDESEP

Arbildo Meléndez Grandes was murdered on April 12, 2020. He was a Kakataibo Indigenous leader of the Unipacuyacu community in the Huánuco Region of the Amazon, in the Puerto Inca province of the Codo de Pozuzo district. Arbildo had long been advocating for his community’s rights to land title, as the community had been formally recognized by the government in 1995. He had denounced the invaders of his People’s lands to various international organizations, and in 2018, he spoke out against illegal logging in the territory before the Environmental Prosecutor based in Ucayali. According to the Ucayali Regional Organization, Arbildo’s death is indicative of the constant risk caused by illegal industries operating in the region. Arbildo’s murder follows that of Justo Gonzáles Sangama, also a community leader and his wife’s grandfather. Justo’s 2017 death was never investigated, nor has anyone been charged to date.

Redy Rabel Abel Ibarra Córdova, who was with Arbildo on a hunting trip the day of his death, confessed to killing him after confusing him with an animal. However, the autopsy showed that Arbildo was shot at point blank range, far too close to be ruled as an accidental death. Nevertheless, Ibarra was released because he was not considered to be a flight risk, and since then, Arbildo’s widow, Zulema Guevara Sandoval, has received death threats that have forced her to move. In her own words, “A narco trafficking mafia that operates in Puerto Inca killed [Arbildo] because he opposed the invasion of the Unipacuyacu lands.” Sandoval, the residents of Unipacuyacu, and the Ucayali Regional Organization continue to demand the rightful investigation and prosecution of those responsible. According to a December 2020 report, the confessed murderer had neither been arrested nor convicted. Public Prosecutor Verónica Julca stated that Ibarra was issued a restricted release by the court due to insufficient evidence for a charge of premeditated murder.

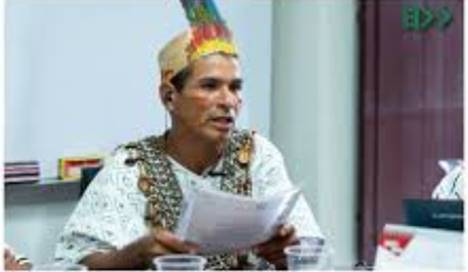

Gonzalo Pío Flores (Ashaninka)

Photo via CIDH - IACHR

Gonzalo Pio Flores, leader of the Nuevo Amanecer Hawai community of the Asháninka Amazon Peoples, was murdered on May 17, 2020 in Santa Rosa de Cahingari, in the Junín region. He advocated for the legitimacy and titling of his community and also for the protection of his People’s land from the illegal logging companies in the area. Witness accuse siblings Bruce, Rosa Linda, and Erika Ernesto Paredes, along with two others, of murdering Gonzalo and severely injuring Gonzalo’s wife, Maribel Casancho Flores. Maribel is also a local Indigenous leader and was walking with Gonzalo at the time of the shooting. She has had to take refuge outside of her community with her children due to the death threats she received. The current whereabouts of the attackers are unknown, and as of September 2020, the investigation by prosecutor Martha Baldeón Berrocal was stalled. The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders is a joint organization with the World Organization Against Torture and the International Federation for Human Rights, and worked to bring awareness and advocate for quick intervention as a result of the deaths.

Indigenous rights defenders from the Nuevo Amanecer Hawai community have long received death threats and been attacked over confrontations challenging the illegal industries in the Amazon. In 2013, Mauro Pío Peña, Gonzalo’s father, also a leader of the community, was also killed as he defended his community's land rights, a crime that has yet to be punished. The continued delay in receiving land title rights and legitimacy form the State for the Gran Pajonal communities in the Amazon region further endangers Indigenous leaders and leaves them susceptible to attacks and targeted crimes from illegal loggers and drug traffickers.

As of January 21, 2021, there has been no progress in justice for Gonzalo’s murder and Maribel’s assault, but there has been engagement on social media to spread awareness and call the murderers to justice. A virtual hearing was held on October 6, 2020 with various representatives of Indigenous groups and organizations, including Maribel, denouncing the Peruvian state before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights for not offering her real protection. “It's a lie that I have protection. They follow me, they take pictures of me. What is going to happen to me when I leave this hearing?” she said.

Acknowledgements

This piece represents months of research by a number of contributors. In addition to Cultural Survival staff members, this work was researched and authored by Cultural Survival interns, including Katia Yoza, Somaya Jimenez-Haham, Marjorie Talavera. Cases were researched in partnership with the RCA's Human Rights Investigations Lab at the University of California, Santa Cruz. We also thank and stand in solidarity with the community members of each individual who have helped bring these cases to light and persevere in seeking justice.